Mary Nguyen, MD, clocks the signs at her local McDonald’s with advertisements for hiring bonuses. As a family physician practicing in Castroville – a rural, underserved community about a 30-minute drive from San Antonio – she is familiar with the challenges of the current labor market.

A referral clerk whom she employed for nearly 15 years recently quit to go work for a bank, citing its retirement plan. And one of her receptionists left for a big, hospital-owned cardiology group that pays better. Patients have noticed the turnover, which has led to longer appointment wait times and prompted some to delay care or seek it elsewhere.

Unlike McDonald’s, Dr. Nguyen’s two-physician practice has thin margins and is paid fixed rates by Medicare and Medicaid. So, she’s hamstrung, unable to raise the cost of her services to pay for salary raises to retain employees. “I can’t even compete with fast food places,” she said.

More than 800 miles away in Alpine, family physician Adrian Billings, MD, says the Big Bend region lost six physicians and four advanced practice clinicians – half of its workforce – between February and November. As a result, his practice, a federally qualified health center with three locations, is booking appointments three to four weeks out and is struggling to meet the demand for same-day urgent visits. He often refers patients to an emergency department, where care is more expensive.

Similarly, the Big Bend Regional Medical Center, a community hospital with 25 beds, recently halved its labor and delivery hours, leaving patients to give birth in the emergency department – without nurses trained in labor and delivery – when it’s closed. The existing staff at both places are picking up the slack, which has fueled burnout.

“I’ve been here for 15 years, but I’ve never seen this rate of attrition,” Dr. Billings said.

Meanwhile, in Denton, obstetrician-gynecologist Joseph Valenti, MD, had eight open staff positions at his private practice in November. He empathizes with employees who are leaving for higher-paying jobs elsewhere, but it’s challenging to keep up with the pace of resignations.

“You can come back from lunch and not have the same staff,” he said. For now, he is limiting clinic time due to staff shortages, and physicians are filling in the gaps, such as by rooming their own patients. But he worries about what will happen in the absence of meaningful relief.

“If something isn’t done, the system is going to collapse,” he said.

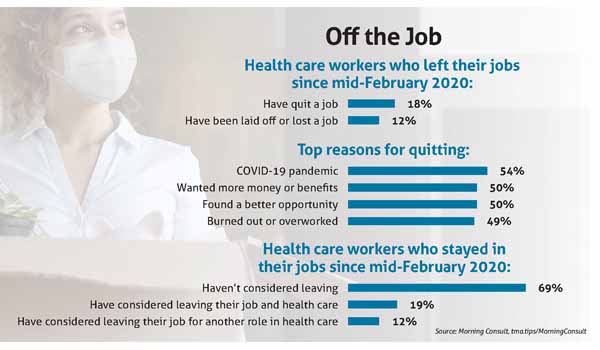

This Bermuda Triangle of workforce woes belies a bigger problem, one that affects employers of all stripes, stretches across the nation, and predates the pandemic. The health care sector lost nearly half a million workers between February 2020 and October 2021, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. A recent poll of 1,000 health care professionals by the data intelligence company Morning Consult found that 19% of respondents who have stayed in their jobs since mid-February 2020 have considered leaving the industry altogether. (See “Off the Job,” page 43.)

Although organized medicine cannot reverse these economic headwinds, Texas Medical Association experts say it can help physician employers by strengthening employee retention efforts to allay staff shortages in the short term and by advocating for policy changes that replenish the health care professional pipeline in the long term.

Compounding factors

The health care labor market is in a vise, with multiple tightening agents. There were workforce shortages going into the pandemic, especially in rural communities. Using 2018 as a baseline year, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) projected the state would be short 10,330 physicians and 57,012 registered nurses by 2032 in a pair of 2020 reports.

Then the pandemic hit, straining the health care system and exacerbating already record-high levels of burnout. Many highly skilled health care professionals opted to retire early or seek jobs in other industries, leaving a vacuum of expertise that remains unfilled and hard to replace quickly. This exodus only heightened the pressure on remaining staff, setting off a vicious cycle of burnout and resignations. (See “An Overworked Force,” October 2021 Texas Medicine, pages 30-33, www.texmed.org/OverworkedForce.)

“It’s just been an ongoing crisis,” said Sam Hogue, MD, a family physician and interim head for primary care and population health at Texas A&M University College of Medicine. “Even if COVID stopped today, that would not solve the problem. We’ve created a big void.”

The latest surge – fueled by the delta variant and rapid spread among the unvaccinated – poured salt in the wound of many health care professionals already suffering from burnout, also referred to as moral injury.

John Henderson, president and CEO of the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals, said hospital staff faced “war-like conditions,” as COVID-19 patients disputed the merits of masking and vaccinations. For physicians and health care workers, the benefits of caring for people were outweighed by the costs of mass death and being maligned.

“Pizza parties aren’t working anymore,” Mr. Henderson said of workplace morale.

There is also heightened competition. Within health care, travel nursing companies, hospitals, and contract agencies can offer much higher pay and signing bonuses than small practices, enticing health care professionals into new roles. Support staff are leaving health care for more lucrative fields.

Bryan Alsip, MD, chief medical officer for University Health System in San Antonio, says many potential applicants for the hospital district’s open IT and finance positions are recruited by other industries that offer better salaries and benefits, including the ability to work from home. “Health care is a team sport,” he said. “Any one of those shortages or breaks in the chain weakens our ability to provide the best care for patients.”

More recently, physician employers and hiring managers have encountered yet another challenge: federal vaccine mandates. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued an emergency regulation on Nov. 4 that affects staff – including physician contractors and those with admitting privileges – at hospitals, nursing homes, federally qualified health centers, and other large health care facilities (tma.tips/CMSRegulation).

TMA practice consultant Teri Deabler says many employers are concerned that this mandate will only increase staff turnover. “For various reasons, there are quite a few health care workers who are against the mandate,” she said.

Staff retention

The reasons for the current health care staffing shortage are thorny, but one workaround is to focus on retaining staff.

“There are things you can’t control right now, such as the lack of skilled workers out there,” Ms. Deabler said. “But there are things you can control. Make sure you’re doing your best to have an office where people feel valued and appreciated. Give them a workplace where they can do their best and have teamwork.”

She advises employers to create structure through rules, provide accountability by enforcing them, and motivate high performers through coaching and recognition. (See “Help Wanted,” page 41.)

“Employees don’t want to come into a chaotic environment,” she said.

Given current staffing shortages, Ms. Deabler says employers should play to employees’ strengths and maximize efficiency by using technology. For instance, a loyal employee in collections who’s too nice to collect payments may be well suited for an open patient-facing position. Practices may also use existing electronic health record systems to streamline processes that would otherwise take up staff time.

Ms. Deabler also encourages practices not to fall prey to the notion that any warm body will do. Hiring out of desperation only begets more turnover, she says, whereas a high-functioning team will fill in until a strong replacement can be found. “You have to figure out how to do more with less,” she said.

This is critical as state and national emergency staffing support phases out in the wake of the delta surge. Last August, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott ordered DSHS to restart a program that distributed more than 8,100 contract nurses and other health care professionals throughout Texas. The Federal Emergency Management Agency operated a similar program. But such programs were winding down as of press time in mid-November.

Stephen Love, president and CEO of the Dallas-Fort Worth Hospital Council, says many of the council’s 90 member hospitals have homed in on workplace morale. “They’ve done things to try to incentivize the workforce other than compensation, to give them more time off, to give them more rest, to listen to their needs,” he said.

Employers have also shifted their hiring strategies. At Hopscotch Health, a children’s urgent care clinic in San Antonio, pediatric nurse practitioner Jimmy Peña takes a proactive approach to recruiting, especially when it comes to hard-to-fill roles, such as medical assistants. “It’s a constant battle because you have to continuously bring people in, interview them, put ’em on a list, and have them on deck for future openings – and hope they’ll be free when you need them,” he said.

Long-term planning

Although the pandemic has made health care’s staffing crisis worse, it has also drawn attention to the problem.

“If you want to be optimistic, the one good thing about COVID is it’s helped increase public awareness of this longstanding health care staffing issue,” said Dr. Hogue of Texas A&M.

Physicians are hopeful that the acuity of the current situation – with chronic staffing shortages cutting into the standard of care – will prompt desperately needed policy changes, for which TMA and its member physicians have tirelessly advocated for years.

For instance, Dr. Nguyen, the Castroville family physician, says the health care system must prioritize primary care and incentivize physicians to practice such specialties as family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics by paying them at higher rates. This would help practices like hers generate more revenue, hire more staff, and see more patients – a win-win-win for her rural, underserved community.

Similarly, Denton OB-Gyn Dr. Valenti says it’s crucial for Medicare and Medicaid payments to keep pace with inflation so that private practices like his can stay afloat and continue to care for vulnerable patients. CMS released its final 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule in early November, cementing a series of mandated pay cuts totaling nearly 10% unless Congress intervenes.

TMA leaders say it’s also critical to nurture the health care workforce of the future. During the regular session in early 2021, the Texas Legislature heeded TMA advocacy in fully funding the state’s Graduate Medical Education Expansion Grant Program, which will help Texas retain its medical school students as residents and, ultimately, full-fledged physicians.

But it’s not enough to address the current and forecasted staffing shortages, Dr. Billings warns. He recently testified before state lawmakers in support of a new proposal: the Texas Center for Rural Health Education, a multidisciplinary training program that would educate rural students of medicine, nursing, pharmacy, social work, public health, and dentistry. The program, he hopes, would recruit students from rural communities into health care and incentivize them to pursue rural health care through loan repayment and scholarship programs.

Born in Del Rio and now practicing in the nearby town of Alpine, he knows firsthand that the rural physician workforce is best grown at home. “The return on investment is significant,” he said.

Tex Med. 2022;118(1):40-45

January/February 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page