“Clinical courage.”

Coined in medical literature, that’s the term Adrian Billings, MD, uses to describe his work as a family physician in Alpine. He says that due to the size and remote nature of his West Texas hometown of 6,000 residents, he’s had to perform unexpected medical procedures to ensure his patients get the care they need.

“When I deliver babies and they’ve had respiratory distress, I’ve had to become the neonatologist, perform the lumbar puncture … intubate them at times,” he said. “But there was not a pediatrician here, there was not a neonatologist here, and I had to raise my hand.”

For rural family physicians like Dr. Billings, the versatility required – be it delivering babies, performing emergency surgeries, or orchestrating end-of-life care – is part of the challenge and reward that comes with practicing where specialists and medical resources are sparser.

Even as state officials report the state’s share of patients to direct patient care physicians per 100,000 people continues to rise, the distribution of physicians in rural areas presents a considerable access-to-care concern. For the 10% of the state’s population living in designated rural counties, Texas Medical Association research shows there’s a direct patient care physician for every 1,128 people. In nonrural counties, that ratio is one to 465.

There are bright spots, however, that indicate the needle can be moved with the right investments. Given this climate, Texas legislators are taking notice with solutions, medical schools are gaining ground with successful rural-specific training tracks, with TMA all the while pushing for further steps to assuage rural health care shortages in Texas.

“We’ve been advocating for rural health care for more than 30 years,” TMA Vice President of Public Affairs Michelle Romero said of the association’s ongoing efforts. “Everyone has been sounding the alarm, and it does take investment … the funding streams are not always certain and predictable.”

The importance of a strong rural physician pipeline has also undergirded TMA’s successful advocacy arguments against scope-of-practice expansions that patients, no matter where they live, deserve high-quality, physician-led care.

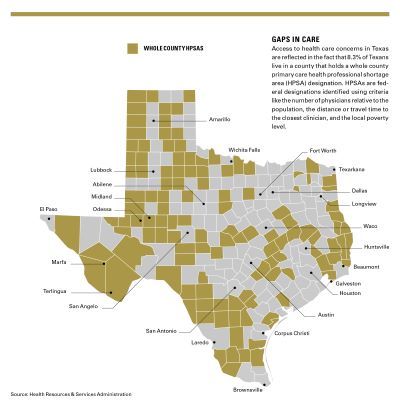

The challenges to improving access to rural care are not insurmountable. Adding 80 primary care physicians to the workforce in the right places could remove all whole county primary care health professional shortage area (HPSA) designations – 80% of which are rural – according to a TMA analysis of U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) data.

Sen. Lois Kolkhorst (R-Brenham), chair of the Senate Committee on Health and Human Services, says rural health was a “major” focus of the 2025 legislative session and touts Texas for addressing the issue.

“Texas has been a leader in this space. I am most proud that our grant programs passed in the last two sessions have become a blueprint for the nation,” she said, adding that budget investments earmarked for rural health initiatives are “helping to create a strong foundation and to ensure there is access to critical services for our people across our state, not just in our urban centers.”

Physicians in rural settings find themselves connected to their patients and communities in ways that transcend medicine. In May, Dr. Billings – also an Alpine Independent School District Board member – got to hand a diploma to a girl he delivered 18 years prior.

“I’m Dr. Billings, not just 8 to 5, but 24 hours a day,” he said of his role in Alpine. “It’s not onerous. It hasn’t been a burden. It’s been incredibly joyful and manageable. And I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Yet he also notes that the cost of running a private practice in places such as his hometown, compounded by payment issues stemming from a higher volume of Medicare and Medicaid patients that rural physicians care for, can be particularly challenging.

He was in private practice from 2007 to 2011 before merging with Presidio County Health Services, designated as a federally qualified health center (FQHC), a federally funded clinic providing health care for medically underserved populations at four locations – Alpine, Marfa, Presidio, and Terlingua.

“I was never able to recruit a private practice physician to come join me when I was private, but as soon as we transitioned to the FQHC model, there were several who were willing to be employed,” he said, citing the advantageous Medicare pay structure and malpractice insurance for FQHCs, plus the appeal of being employed rather than taking an ownership stake in a private practice, as selling points he’s utilized.

FQHCs like Dr. Billings’ are helping to fill voids – and new legislation like House Bill 3151 may provide further assistance with the volume of Medicaid claims by expediting credentialing by Medicaid managed care organizations for FQHCs and physician practices.

While being in a FQHC has allowed him more focus on medicine, the rural setting is still fraught with access-to-care roadblocks.

“Patients arrive to us sicker with more comorbidities. Because there are less of us practicing, it takes longer to get an appointment, and then if they need access to medicine or specialty care, that can be a real challenge for them,” he said.

He also notes that less access to labs and radiology services, plus longer wait times for diagnostic services, factor into the equation, and for the rural physician that can be “incredibly stressful.”

Access to health care concerns in Texas are reflected in the fact that 8.3% of Texans live in 124 counties that hold a whole county primary care HPSA designation as defined by HRSA.

Celeste Caballero, MD, a pediatrician who practiced in San Angelo before moving to a Texas Tech University-affiliated clinic in Lubbock, says one of the biggest quandaries for rural physicians is knowing when and how to safely move a patient to an urban setting where more medical resources are available.

“When I was in San Angelo, I would basically have to stabilize these critically ill patients the best I could on the phone with an intensive care doctor, usually from San Antonio,” Dr. Caballero said of pediatric patients she sought to move to intensive care units. “We then literally ship them out as quickly as possible on a fixed-wing airplane or helicopter, or sometimes ground transportation, depending upon the weather.”

Even in what was then a city of about 90,000 people with two hospitals, Dr. Caballero had to make those calls while taking on multiple roles including seeing clinic and inpatient pediatric patients, newborn nursery patients, and even some routine surgical procedures – “the reality of what small communities face,” she said.

Aid for the struggling hospitals physicians rely on is another critical component in bettering Texas’ rural health landscape.

Texas has 156 rural inpatient hospitals, 84 of which are at risk of closing, with 21 of those at immediate risk, according to a July report by the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform.

Since 2015, 14 have closed, and four have converted to rural emergency hospitals (REHs), a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) designation that allows emergency medicine and observation care but requires closing inpatient services.

“There’s really no fluff in these rural hospitals to take a financial hit,” said Dr. Billings, concerned that potential federal Medicaid cuts could contribute to rural hospitals either converting to REHs or closing altogether, “creating a hospital desert and less access to care for a community.”

Rural hospitals are especially essential for expectant mothers, according to Dr. Caballero.

“If we’re going to prevent a mom from having to drive two and a half hours in labor, we’ve got to maintain those hospitals in these rural communities, to foster those deliveries and newborn care,” she said.

To bolster the viability of rural hospitals, the legislature this year passed House Bill 18 – sponsored by Rep. Gary VanDeaver (R-New Boston), chair of the House Committee on Public Health. HB 18 launched several key initiatives:

- Creating a State Office of Rural Hospital Finance, providing rural hospitals and health care systems with technical assistance for federal financial programs including Medicaid;

- Establishing an academy for rural hospital officers and health care professionals, providing professional development and continuing education; and

- Establishing a financial stabilization grant program and an emergency hardship grant program to support rural hospitals.

HB 18 also expands funding for obstetrician-gynecologist and emergency medicine physician recruitment, plus maternal behavioral care and child and perinatal mental health care, in rural areas. It also resumes support for the Rural Hospital Grant Program, which initially appeared in the 2024-25 budget, additionally supporting maternal care.

Senator Kolkhorst observed HB 18 in particular “signaled the strong support and investments that Texas lawmakers have made for our rural hospitals and health providers.”

She helped champion the initial program rollout during the 2023 session, providing $50 million for what she described as “struggling rural hospitals.”

“With this grant program, Texas staved off closures of some rural hospitals and made investments for critical services,” she said.

One potential new funding source for rural hospitals comes from the federal budget bill, which earmarked $50 billion for the Rural Health Transformation Program for distribution over five years.

The program boosts rural hospital funding, with 50% of the fund divided equally among all states that apply for the CMS funding by the Dec. 31 deadline.

The other 50% will be distributed to states based on a formula developed by CMS, factoring in “a state’s rural population, proportion of health care facilities in rural areas and situation of hospitals that serve a high proportion of low-income patients,” according to a U.S. Senate Committee on Finance fact sheet.

The program allows funds to be used for “promoting evidence-based interventions to improve prevention and chronic disease management,” according to the fact sheet, indicating that some funds could flow directly to physician practices.

“That legislation will provide funding to a myriad of rural health care providers, in addition to hospitals,” said Senator Kolkhorst, noting that Congress looked to Texas’ work on rural health care when crafting the program.

“This is great news for Texas,” Senator Kolkhorst said. “It also provides a strong foundation to help rural health care providers build self-sustaining programs and services.”

Citing multiple studies within the past decade, including one from the National Institutes of Health showing declining numbers of rural medical students, Dr. Billings says Texas could be doing “a better job” of feeding that pipeline.

In addition to practicing medicine, Dr. Billings is associate academic dean of Rural and Community Engagement with Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, working three days a week from its Permian Basin campus in Odessa.

“The two biggest predictors of future rural medical practice for a medical student are rural origin, and then regardless of your origin … that you had exposure to rural medicine during your medical school or residency training,” said Dr. Billings.

Rural residency programs help prepare physicians planning to practice in rural settings and Texas medical schools, with investments from the Texas Legislature, are making headway.

The 2026-27 state budget allotted $3 million of funding for rural residency training tracks – the second straight session TMA was able to successfully secure that level of support. Funding was awarded to six programs statewide, with each getting $500,000 for the two-year cycle.

An additional $1 million was needed for the 2026-27 grant cycle to enable the first-year residency positions to be refilled as residents progressed to the second year of training; however, that additional funding was not received and residency programs will need to obtain that funding from another source.

Among the six programs is one run by the Texas A&M University Naresh K. Vashisht College of Medicine, which commenced in July.

Texas A&M’s College of Medicine also collaborates with the school’s Colleges of Nursing and Pharmacy, plus the Rural and Community Health Institute, on the Rural Engagement Program at Texas A&M Health, which received $15 million in the 2024-25 state budget, and $30 million in the 2026-27 state budget, used for multiple workforce improvement and rural hospital and clinic operational improvement programs.

Texas A&M’s rural program has grown significantly due to the vision and leadership of its dean, Amy Waer, MD, starting with rural medical student rotations.

“The vast majority of medical students are from urban areas,” said Kia Parsi, MD, executive director of Texas A&M’s Rural and Community Health Institute. “Many of them have never set foot in a rural community. How do they know what they don’t know? How could they even consider a rural environment if they’ve never been in a rural environment?

“So specifically, with [Texas A&M] College of Medicine, the purpose of these student rotations is not just for them to learn how to treat pneumonia or congestive heart failure … They’ll get plenty of that training in other rotations,” he said. “What we want is those students, when they’re driving away from their two-week rotation, to look back and say, ‘Now I know what it’s like to live and work as a physician in this town, and maybe I consider that as an opportunity.’”

Dr. Parsi notes that increasing medical student interest in rural medicine must be followed by increasing the opportunities for rural-focused residencies. With the state grant, Texas A&M was able to expand its Bryan-based family medicine residency program. It still includes 10 residents doing three years of training in Bryan and College Station hospitals, but now has added two residents, who train for a year alongside those residents, then train for two years in Madisonville, nearly 40 miles away, to work in a critical access hospital and see patients in a rural clinic setting.

Texas A&M has also created a K-12 “school to scrubs” pathway program to inspire rural students to consider health care career possibilities. It offers, among an array of activities, a Mini Med Camp, a College of Medicine-hosted immersive overnight experience for high school students.

While these programs provide rural patients greater access to health care while residents are active, the ultimate goal is to get more physicians into rural communities. As Dr. Parsi notes, it doesn’t take many to make a big difference.

“If you have a county, and you have three physicians and one is retired, and you replace that one, you’ve just increased the physician population by a third in the entire county,” he said. “These small numbers, especially with increasing the number of rural-focused residencies, can make high impacts geographically to these rural counties.”

Dr. Billings adds that telemedicine has been a boon to rural health, in which TTUHSC has been a pioneer since the 1990s and for which TMA continues to advocate additional funding. One project he’s become involved with, Medicine on the Move, is bringing new telemedicine capabilities to small West Texas outposts like Balmorhea, Coyanosa, and St. Lawrence.

“We drive this telemedicine equipment that has diagnostic peripherals, a stethoscope to listen to, an ophthalmoscope to look at the retina, an otoscope to look in the ear, and then a dermatoscope to look at skin lesions,” Dr. Billings said.

He explained that an on-site medical student operates the devices as the patient connects online with an Odessa-based resident physician.

“It’s more than just a Zoom visit where you’re just doing an audio interview. It has some diagnostics to make the exam a little more robust.”

Although it did not make it to the finish line, TMA also came to the table with an innovative solution to further physician-led health care in rural Texas.

Senate Bill 2695, sponsored by Senator Kolkhorst, proposed a Rural Admission Medical Program – a concept co-authored by Dr. Billings, and modeled on the Joint Admission Medical Program – to financially support rural students interested in pursuing medical school with the intention to return to practice in their communities. The bill also proposed new ways to build up physician-advanced practice registered nurse teams in smaller counties.

“I plan to consider some form of SB 2695 in the next session,” Senator Kolkhorst said, noting that she’ll look for input from health care professionals leading up to 2027 – including those at TMA who stepped up on behalf of that proposal.

“TMA provides feedback on the impact of all bills we file in the Senate related to health care, but it also provides essential information on the importance of physician-directed services,” she added. “The organization has a number of experts and offers different ideas on how to refine legislation and where to direct health care resources. I value their input and am grateful to have their support on many of these great policy initiatives.”