Although the omicron variant deferred its expiration date again, the PHE will eventually end. This should be a cause for celebration, but the status change will likely reverse pandemic-era gains in Medicaid, telemedicine, and private coverage that physicians would like to see preserved.

The Texas Medical Association and other parts of organized medicine are diligently keeping track of the PHE and its implications for practices. Amid the ongoing surges and other pandemic pressures, however, many physicians feel unable to prepare for the eventual end of the PHE or even to educate themselves and their patients about what’s at stake.

Louis Appel, MD, chief medical officer and director of pediatrics for People’s Community Clinic in Austin and president-elect of the Texas Pediatric Society, says he has many questions about what post-pandemic operations will look like. For example, he knows the Texas Legislature passed new laws expanding Medicaid coverage and telemedicine access. But he wonders how those laws compare with PHE-era policies – and what benefits may be lost in the transition. “It’s unclear, when the PHE ends, what has changed in the law,” he said.

Tom Banning, CEO of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, shares these concerns. “[Physicians are] so in the thick of things right now that they’re just treading water at this point and haven’t had a chance to think through the consequences of when the public health emergency ends,” he said. “We’re going to be in for a long and difficult ride once the public health emergency ends.”

Medicaid Eligibility

Millions of Medicaid patients across the U.S. – 15 million including 5.9 million children, according to the Urban Institute – are at risk of losing their coverage when the public health emergency (PHE) ends.

The federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act increased federal Medicaid matching dollars by 6.2% for states that agreed to maintain Medicaid coverage for anyone enrolled in the program from March 20, 2020, through the end of the PHE, including Texas. In Texas, Medicaid enrollment increased by 1.2 million patients – or nearly 24% – between February 2020 and October 2021, according to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC).

HHSC has told TMA that it will not automatically drop Medicaid patients’ coverage at the end of the PHE until eligibility checks are conducted, as required by federal policy. Many will be required to renew their coverage, while others will be deemed ineligible.

The physicians who care for such patients face tough decisions about how much uncompensated care their practice can withstand and how to help patients navigate this transition. But repeat extensions make preparation difficult, says Helen Kent Davis, associate vice president of governmental affairs for the Texas Medical Association.

“Through the public health emergency, [patients] have not had to jump through as many hoops to maintain Medicaid … which is wonderful and huge for public health,” said Emily Briggs, MD, a family physician in New Braunfels. “With the public health emergency ending, they will now have to start jumping through hoops that they didn’t necessarily need to, and those hoops will make it … so that people who need that access to care will potentially lose that access to care.”

Postpartum women have been one of the main beneficiaries of continuous Medicaid enrollment during the PHE, says Ms. Davis. Other populations, including children, have also benefited.

Dallas obstetrician-gynecologist Charles Brown, MD, knows firsthand how critical this kind of extended coverage can be. He cites as an example a patient who experienced multiple pregnancies. During the first, she qualified for Medicaid coverage and received prenatal care, including a Pap smear, which showed precancerous cells. She then received an appointment for a follow-up colposcopy after she gave birth. However, because her Medicaid coverage ended after delivery and because she couldn’t afford private insurance, she didn’t make it to the procedure. This scenario repeated itself through four more pregnancies, leaving her with a cervical cancer diagnosis while caring for five children – ranging in age from in utero to a teenager.

“The system failed that woman,” said Dr. Brown, who is also chair of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists District XI (Texas). “If she would have had her Medicaid, she wouldn’t have missed that appointment.”

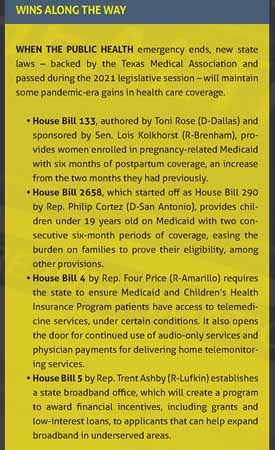

The Texas Legislature enacted a new law to reduce these kinds of scenarios.

But other patients who have benefited from continuous Medicaid enrollment during the PHE still face a potential coverage cliff. Many at risk of losing Medicaid coverage when the PHE ends will not have another coverage option because Texas has not extended health care coverage to low-income working adults and parents as allowed by the Affordable Care Act. Although temporary federal marketplace subsidies for people earning above the federal poverty level will help, many Texans likely will become uninsured because they earn too little to qualify for marketplace coverage but too much for Medicaid, Ms. Davis says, falling into what’s known as the “coverage gap.”

This drop has serious implications for physicians, says Austin pediatrician Louis Appel, MD, president-elect of the Texas Pediatric Society. When a patient loses coverage, physicians are faced with providing the best and most appropriate care while also identifying more affordable alternatives; communicating the risks of such options; and searching for stopgap support, such as patient assistance programs.

“The lack of access to services for the patient, that’s the primary concern,” he said. “[But] it does take considerably more effort to try to find the workarounds, if they can be found, for children that don’t have coverage.”

How to prepare

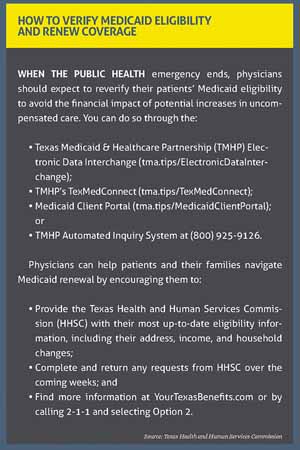

Any decision to allow the PHE to lapse will come with a 60-day notice, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Still, Texas physicians should prepare for this possibility by scheduling services as soon as possible for patients who might lose coverage; familiarizing themselves with other potential coverage options for their patients, such as the federal marketplace or women’s health programs; and evaluating the financial impact of potential increases in uncompensated care. They also should expect to reverify patients’ Medicaid eligibility when the PHE expires.

HHSC has encouraged Medicaid recipients to prepare and submit their renewal packet sooner rather than later to ensure their coverage does not lapse when the PHE ends.

“Millions of Texans will need to have their eligibility redetermined at the end of the public health emergency because they would have been determined ineligible but had their coverage maintained,” Ryan Van Ramshorst, MD, chief medical director of Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program services at HHSC, wrote in an email interview with Texas Medicine. “The quicker a person can complete their renewal, the better we can ensure they continue to have access to important health care services.”

This process can prove challenging. Many Medicaid patients must update their information because of a new address, for example, but may find that the form to do so is being sent to their former residence. Caller wait times for HHSC’s 211 help program are sometimes long, which adds to the difficulty.

TMA and others in organized medicine are working to address these administrative challenges, including by asking HHSC to establish a toll-free hotline for this purpose. In the meantime, Dr. Van Ramshorst writes that physicians can help patients and their families by reminding them to provide HHSC with their most up-to-date information and to promptly complete and return any requests from HHSC.

Telemedicine Improvements

Like continuous Medicaid enrollment, the expansion of telemedicine during the pandemic has emerged as a silver lining throughout the tempest of COVID-19. As the onslaught of COVID patients has overburdened the health care system and compromised care for patients seeking elective procedures, telemedicine access has expanded, especially for behavioral health services, offering patients newfound convenience.

Physicians want to largely cement these gains, but the end of the public health emergency (PHE) could reverse them instead.

Since the onset of the pandemic, state and federal governments have eased regulatory and payment barriers to delivery of health care via telemedicine. Private health plans and state agencies have followed suit by allowing physicians to use audio-only telemedicine, removing site restrictions, and ensuring payment parity – if only temporarily.

As the PHE lingers on, however, some health plans have started to rescind such flexibilities, says Rodney Young, MD, a family physician in Amarillo and chair of the Texas Medical Association Council on Socioeconomics. If audio-only telemedicine visits are not paid for at the same rate as in-person visits, for example, many physicians will stop offering them because of the financial repercussions.

“It’s serious,” he said of the potential consequences.

Dallas obstetrician-gynecologist Charles Brown, MD, hopes payers continue to cover such services once the PHE ends. During the early weeks of the pandemic, the public hospital where he practices implemented audio-only prenatal visits for its patients, many of whom are covered by Medicaid and lack access to broadband and consistent transportation.

“Once they get to the hospital, they get good care, but getting there is a challenge,” he said. “So telemedicine was a huge boon for our ability to continue to contact our patients.”

This continuity of care has proven benefits.

A study of more than 4,000 audio-only prenatal visits conducted in late March 2020 at the hospital where Dr. Brown practices showed wait times fell, among other benefits, as a result of telemedicine, according to a journal article published in the August 2020 issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology. On average, 88% of virtual visits were completed as scheduled, compared with 82% of in-person visits, and 99% of patients who participated in a follow-up survey reported their needs were met during their audio-only virtual visit.

Although it remains unclear how payers will handle telemedicine coverage post-PHE, certain advances in telemedicine will live on in Texas thanks to progress during the 2021 legislative session.

These legislative changes are intended to expand access to telemedicine, for example, by expanding broadband across the state. But TMA continues to advocate for additional changes needed to ensure telemedicine’s momentum beyond the PHE, including payment parity. (See “Telemedicine’s Tipping Point,” November 2021 Texas Medicine, pages 44-47.)

Louis Appel, MD, chief medical officer and director of pediatrics for People’s Community Clinic in Austin and president-elect of the Texas Pediatric Society, says the clinic began offering telemedicine services as a result of the pandemic because of state policies that incentivized doing so. If those policies change when the PHE ends, the clinic may have to reevaluate. “Our baseline with telemedicine has been with all of the pandemic flexibilities in place,” he said.

Private Payers

The public health emergency (PHE) has resulted in a mixed bag of responses from private payers, and their policies are liable to change when it ends, says Carra Benson, the Texas Medical Association’s manager of practice management and reimbursement service. Like the moving target of the PHE deadline, fluid payer policies spell uncertainty for physician practices. But there are steps they can take to prepare for this eventuality.

Most private payers have indicated they will continue to fully cover COVID-19 testing, treatment, and vaccines as well as certain telemedicine visits through the end of the PHE, Ms. Benson says. When it ends, however, PHE-related federal waivers will end, too, leaving private payers to decide whether to revert to prepandemic policies.

This uncertainty can be challenging for physician employers, says Tom Banning, CEO of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians. He anticipates some private payers will stop fully covering certain services, such as audio-only telemedicine visits and COVID-19 testing, when the PHE ends. If they do so, patients will have to assume the costs, which means many will opt out of such services because they can’t afford it. This could have serious public health consequences and make it harder for physicians to care for their patients effectively.

Rather than alleviate pandemic-related challenges, the end of the PHE could exacerbate physicians’ troubles – including staffing shortages, supply chain issues, and assaults on medical expertise – and remove important tools from their toolboxes. “Further uncertainty is just going to add to that stress and burnout and the challenges that are already placed on a fragile health care system that’s been dealing with this pandemic for the last two years,” Mr. Banning said.

Practices can take steps now to ease the transition when the PHE ends, Ms. Benson says. Private payers have consistently communicated changes to their PHE-related policies in advance, giving practices time to adjust.

TMA also keeps tabs on changing billing and coding requirements so busy practices don’t have to sort through individual payers’ websites, which can take hours. Ms. Benson encourages practices to consult these resources regularly to avoid any surprises.