"El Paso’s 2019 Measles Outbreak Hits 5,000 Cases”

That headline was never written and – thanks in part to dedicated work by El Paso physicians and health care workers – never will be.

In July, El Paso did have a measles outbreak, which is defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as three or more related cases. Though as of press time Texas had 21 cases overall, El Paso’s cases constituted the only official outbreak so far, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS). But it involved only six cases and officially ended in September, according to the City of El Paso Department of Public Health.

El Paso-area physicians understand that the outbreak could have been much worse, but it wasn’t – thanks largely to vaccination rates that are among the highest in Texas.

“The fact that we were immunized in the community helped contain it,” said Hector Ocaranza, MD, an El Paso pediatrician who also serves as the health authority for the City of El Paso Department of Public Health.

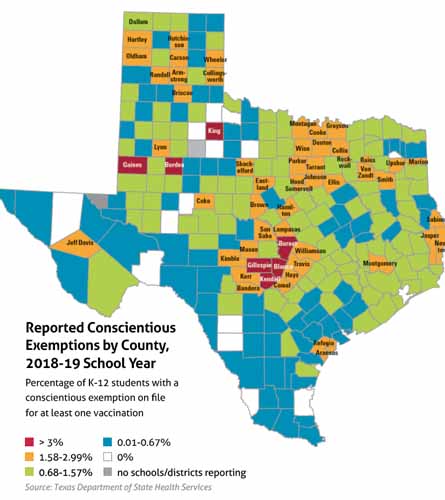

However, the headline above could have reflected reality if El Paso had the pockets of unvaccinated people now found in most of the state’s heavily populated counties. (See “Reported Conscientious Exemptions by County, 2018-19 School Year,” page 43.)

In fall of 2018, the Texas Pediatric Society asked the Framework for Reconstructing Epidemiological Dynamics (FRED) at the University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Public Health to simulate measles outbreaks in Texas metropolitan areas if their vaccination rates were just 10% lower than their current levels.

For El Paso, the result was 5,484 cases of measles, not six. Among them would be 1,602 “bystanders,” which includes those for whom the vaccination failed (3% of people do not gain immunity after vaccination), those who are ineligible for vaccination due to medical conditions, and unvaccinated adults, according to FRED. The remaining 3,882 would be school children whose parents refused the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine.

Texas’ coverage has weakened for measles and all vaccine-preventable diseases since 2003, when the state began letting parents refuse vaccines for their school-age children for reasons of conscience. The state’s overall exemption rate is now 1.2%, compared with El Paso County’s 0.6%. Statewide, the exemption rate is still below the 5% threshold for preserving herd immunity with measles. But the state has a number of hotspots for vaccine exemptions.

A 2018 study published in the Public Library of Science found that Collin, Harris, Tarrant, and Travis counties are all vulnerable to disease outbreaks because so many school children are now exempt from vaccination. Measles is a particular concern because it’s so contagious, but every vaccine-preventable illness is a potential problem.

“The high numbers of [non-medical exemptions] in these densely populated urban centers suggest that outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases could either originate from or spread rapidly throughout these populations of unimmunized, unprotected children,” the report said.

So how is El Paso bucking this trend? The answer isn’t simple, says Gilbert Handal, MD, a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) in El Paso. Some aspects of it, like physician coordination and advocacy in the schools and community, could be replicated in other parts of the state. Other pieces are just traditional parts of El Paso’s culture, such as an old-fashioned trust of physicians among most patients.

“It’s a conservative society from the point of view of relationships between physician and patient,” said Dr. Handal, a consultant to the Texas Medical Association Committee on Infectious Diseases. “And people really believe, at least in the pediatric community, that the physician is telling them what is best for the child and for the family.”

A sense of urgency

El Paso is a famously busy place. It has three international bridges that span the U.S.-Mexico border, and it’s one of the highest-volume border crossings in the U.S. Together with Ciudad Juarez in Mexico, the El Paso area makes up one of the largest binational regions in the world.

El Paso also sees a lot of international travel because of Fort Bliss, a nearby U.S. Army base. The first two cases in El Paso’s measles outbreak probably originated there, according to the City of El Paso Department of Public Health. The outbreak affected three adults and three toddlers, and gave the region its first cases of measles since 1993.

El Paso frequently sees diseases that most other parts of the state don’t see, such as tuberculosis, says Jennifer Molokwu, MD, a family physician and associate professor at TTUHSC-El Paso. Travelers bring diseases like Zika, chikungunya, and dengue, according to City of El Paso Department of Public Health.

“We have high uninsured rates and high poverty rates,” Dr. Molokwu said. “We see a lot of things that are not common in the rest of Texas just because of the movement of people back and forth from the border. So there’s more of a sense of urgency [about infectious diseases]… It’s top of our minds.”

Many people outside El Paso assume that means immigrants from south of the border are also the main culprits for bringing in vaccine-preventable diseases. Just the opposite is the case, says Dr. Ocaranza. Most immigrants moving through El Paso come from Mexico and Central American countries, and the vaccination programs in those countries are more robust than or comparable to that of the U.S., he said.

“I’m actually happy to have Mexico next to us because they’re protecting us,” he said.

Also, in Hispanic culture, grandparents tend to be very involved with the raising of children, Dr. Ocaranza says. Those grandparents often are old enough to have had first-hand experience with vaccine-preventable diseases, so they are valuable allies in driving up vaccination rates.

“In the olden days, they would see a case of polio and that kid would never walk, and they don’t want to see that again,” Dr. Ocaranza said.

Instead, he’s more concerned about travelers from Europe, where declining vaccination rates have helped cause a resurgence in measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases. Also, there have been serious measles outbreaks in Israel, the Philippines, and Ukraine.

Communication and coordination

Organized medicine, including the El Paso Pediatric Society, El Paso County Medical Society, and TMA help coordinate efforts in El Paso at times, Dr. Ocaranza says. Many physicians also work through the El Paso Immunization Coalition, an alliance of physicians, nurses, social workers, and pharmacists as well as numerous businesses and nonprofits, Dr. Molokwu says.

But the pediatric community most responsible for dispensing vaccines is relatively small and close-knit, Dr. Ocaranza says, so much of the work in coordinating vaccine efforts is done informally.

“It’s a big community but we act like a small community because we all see each other and talk to each other,” he said. “When you keep that communication open, it’s a lot easier [to work together]. If any of us have an interesting case, we all kind of talk about it.”

El Paso’s leadership in vaccines is probably strongest in human papillomavirus (HPV), a vaccine that – unlike MMR and most other shots – is not required for school attendance and normally has a much lower coverage rate than other vaccines. Texas ranked 47th among U.S. states in HPV vaccination coverage, according to a 2017 report by The University of Texas System Office of Health Affairs.

But the same report called El Paso County “the bright spot in Texas HPV vaccination coverage.” The estimate of up-to-date adolescent HPV vaccination coverage for the El Paso area was 66% in 2016, compared with 32.9% statewide, according to the National Immunization Survey-Teen. If the county had been its own state, it would have ranked just below nation-leading Rhode Island, with 70.8% coverage.

Dr. Handal helped make that rate possible by creating a comprehensive program that combined the efforts of local physicians, county health officials, school nurses, parents, and community groups. The program provided physician-to-physician education about HPV while using local agencies and organizations, as well as the news media, to educate parents about the need to vaccinate.

Due to lack of funding, only parts of the program were implemented. But a similar one could be modified to work in other parts of Texas, Dr. Handal says – depending on how well local physicians and other health related entities get along.

“All politics is local,” he said. “It all depends on the relationship that people in the academic environment or the infectious disease environment have with the rest of their colleagues. In my case, I frequently talked with [family physicians and pediatricians]. I visited with them in their offices. I trusted them, and they trusted me.”

El Paso has its share of anti-vaccine activists, so education remains important, says Dr. Ocaranza.

For physicians, speaking out and coordinating pro-vaccine efforts can have a powerful impact, says Jennifer Shuford, MD, infectious disease medical officer for DSHS.

“In communities where there is a physician champion for vaccines, [DSHS staff sees] higher immunization coverage rates,” she said. “The physicians are very important to getting that vaccine message out.”

Dr. Molokwu recently received a $1.9 million grant for three years from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) to reach uninsured and underinsured people in the El Paso region about HPV, particularly youth.

“We know that a lot of our younger adults do almost everything off social media,” she said. “That’s where they get information about traffic, it’s how they find out what’s happening where. So those are important [lines of communication] that we need to capture.”

Tex Med. 2019;115(11):40-44

November 2019 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page