Bridge City family physician Amy Townsend, MD, transitioned to direct primary care (DPC) five years ago, a switch she says allowed her to claim full authority over the care she provided and payment she accepted – with one exception: health savings accounts (HSAs), which patients could not use to pay for DPC services.

Thanks to newly enacted federal regulations, however, patients can now pay for DPC arrangements with their HSAs, a change that Dr. Townsend says may lead to increased access to care for patients and less red tape for clinicians.

The change took effect Jan. 1 under Congress’ budget bill, known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), which included a $40 billion expansion to tax-preferred HSAs.

“This is going to give patients and doctors [who provide primary care services as defined by OBBBA] a lot more control and flexibility, without insurance interference,” said Dr. Townsend, chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Independent Physician Practice (IPP).

DPC allows patients to pay a recurring membership fee directly to a primary care physician for medical services, bypassing the need for traditional insurance billing.

For example, Dr. Townsend’s DPC practice allows her patients to purchase a membership that grants unlimited access to certain primary care services – like routine screenings and acute-care visits – directly from her practice without having to file an insurance claim. Patients pay a monthly fee to access care as needed, without having to make an additional payment at the time of service.

“The environment I used to practice in did not allow me to provide care the way I wanted to. I had minimal freedom to make what I considered the best decisions for my patients, free from outside constraints,” she told Texas Medicine last year. “When I started my own [DPC] practice, I could finally become the type of physician that I’ve always wanted to be.”

In 2023, the annual deductible for employer-sponsored insurance plans, the most common form of coverage, cost patients $1,735 on average, according to an October 2023 study by KFF, not to mention cost-sharing requirements regardless of whether they met their deductible.

In comparison, according to a 2024 data brief from the American Academy of Family Physicians, monthly DPC membership fees range from $20 to $49 for children and $50 to $100 for adults ages 65 and under. Monthly membership fees for families were reported at $100 or higher. Over half of DPC arrangements, 62%, charge an enrollment fee and 7% charge a per-visit fee, according to the report.

Dr. Townsend said DPC arrangements “empower patients to choose the care and health care professional that best fits their needs,” as they are not tied to a specific employer or insurance plan. This allows for more personalized and cost-effective health care decisions, she says – an allowance that now extends to patients with HSAs.

Previously, participating in a DPC arrangement would disqualify patients from having a high-deductible health plan (HDHP), which is necessary to qualify for an HSA. Additionally, federal tax law prohibited HSAs from being used to pay for DPC membership fees. The new law changes this, provided the arrangement meets certain federal requirements:

- The arrangement must provide services consisting solely of primary care services provided by primary care practitioners;

- The arrangement cannot provide procedures that require the use of general anesthesia, prescription drugs other than vaccines, and laboratory services not typically administered in an ambulatory primary care setting;

- The sole compensation is a fixed periodic fee, without per-visit charges; and

- The aggregate cost of arrangements cannot exceed the allowable amounts established by the law, which are $150 per month for individuals or $300 per month for family arrangements, with annual adjustments for inflation. These limits apply to the total cost of all DPCs a patient may have.

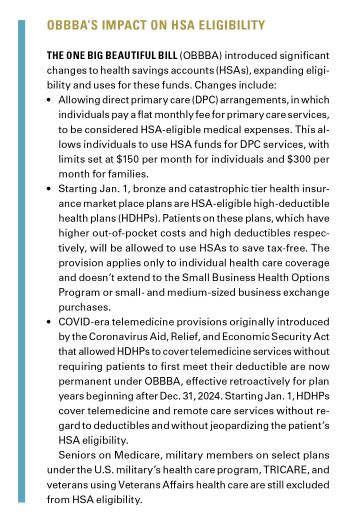

Other changes to HSAs under OBBBA include allowing bronze and catastrophic tier health plans to be HSA-eligible HDHPs, and certain COVID-era, HDHP telemedicine provisions to become permanent, both effective Jan. 1.

Although she recognizes not all physicians can transition to DPC, Dr. Townsend still believes DPC models are one method to curb burdensome health care costs while allowing physicians to provide the care they deem necessary.

However, OBBBA’s new HSA provisions “do not come without their limitations,” said Kim Harmon, TMA’s associate vice president of innovative practice models.

For example, patients participating in DPC may be disqualified from contributing to their HSAs if their membership fee exceeds the fixed periodic fee limits set by OBBBA – $150 for individuals and $300 for families – or if their physician provides excluded services, even if they deem those services necessary.

“I don’t love it when the government makes decisions about the value of a specific service that we’re providing as physicians,” Dr. Townsend said. However, the cap falls “well within the range of membership fees [DPC] physicians typically offer,” she said.

Additionally, under OBBBA, DPC arrangements must provide solely “primary care services” by “primary care practitioners.” This means while specialists can offer DPC arrangements, OBBBA outlines patients cannot use their HSAs to pay for care provided by a specialist if they do not offer primary care services.

According to Texas House Bill 541, passed during the 2025 legislative session, any physician or health care practitioner in the state can enter into a DPC agreement, defined as a signed written agreement under which a physician or health care practitioner would agree to provide health care services to a patient in exchange for a direct fee for a period.

Additionally, although OBBBA defines primary care services to include medical care provided by primary care practitioners, the law does not explicitly define what services count as primary care.

Austin family physician Christopher Larson, DO, who practices in direct care, says these nuances could unintentionally limit the type of care physicians under the model can offer. For example, OBBBA specifies DPC physicians can only offer labs that are typical for primary care – but Dr. Larson himself frequently orders labs for his patients, in coordination with specialists, that health plans would typically define as specialty care.

Dr. Larson says this lack of clarity could result in confusion about what primary care services are covered under DPC arrangements, while leaving room for HSAs to decide what is and what is not. It also may lead to patients being denied coverage for necessary services.

“Primary care physicians offer more types of care than you’d expect. There is some concern among DPC docs about the vagueness of the new law,” Dr. Larson said.

However, that vagueness could offer DPC physicians more leeway in the type of care they provide without interference from health plans. And “even without further explanation or change, I do think this will help Texans’ access to care. More patients now have a choice about the care they receive,” Dr. Larson said.

Dr. Townsend says the IPP committee will evaluate potential unintended consequences of the new provisions, such as patients struggling to navigate which services are HSA-eligible and which are not. TMA continues to monitor the broad scope of OBBBA’s potential impact on patients and physicians.

“Hopefully over time, as the DPC model grows, it will lead to the ability for specialists to offer similar structures,” Dr. Townsend said. “But when you create a situation like this where patients can contribute to an HSA and then use those pretax expenses for primary care, it tends to make care less expensive, which is the big thing.”

How the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) could transform Texas health care

A Mixed Medicaid Bag: Federal changes may narrow certain Medicaid eligibility provisions, boost others

Immigrant Eligibility Provisions: Federal officials approved these new immigrant eligibility provisions for Medicaid, Medicare, and the Affordable Care Act under OBBBA.

Disrupting the Marketplace: How the ACA expiring tax credits could impact health care costs

ACA in Texas: What parts of the state do Texans carry ACA health plans?

Community Support: Texas aims to use federal funding to address rural health care challenges

One Big Beautiful Bill Act changes: Key modifications introduced by the 2025 federal budget bill – known as OBBBA – that affect major health care programs.

Cap at Hand: Federal loan changes could exacerbate medical students’ financial challenges

How other federal budget items could affect Texas

Budget Crunch: Uncertainty besets Texas’ public health infrastructure as federal funding streams dry up

Concerns Remain: Medicare physician fee schedule retains payment increase and concerning cut

Alisa Pierce

Reporter, Division of Communications and Marketing

(512) 370-1469