A rural health care shortage is nothing new to Texas physicians and patients. But the problem has become especially difficult for women seeking maternity care in lightly populated regions like West Texas, says family physician Jennifer Liedtke, MD, of Sweetwater.

“In order to see maternal-fetal medicine [specialists], our patients are driving almost an hour one way,” she said. “It’s really frustrating getting them the help that they need.”

The lack of health care rural women face is reflected in national data on maternal mortality. In the most rural U.S. counties (areas with populations of less than 50,000 residents), the maternal mortality ratio was 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 14.6 in large metropolitan counties (areas with a population above 1 million). That’s according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 2011 to 2016.

“We’ve shown that the farther women have to drive to get maternal care, the higher the morbidity and mortality rates become,” said Dr. Liedtke, a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Reproductive, Women’s, and Perinatal Health. “So we’re trying to serve these women, but we don’t have a lot of the resources that obviously some of the bigger hospitals have.”

The struggles Dr. Liedtke faces are part of a nationwide trend tied directly to the poor financial health of rural hospitals. About 40% of rural hospitals – or 892 – across the U.S. are at immediate or high risk of closure, according to a 2022 study by the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform. In Texas, the problem is worse. Fifty-five percent of rural hospitals – 81 in all – are at immediate risk of closing.

Some of those hospitals are in worse shape than others, says John Henderson, president and CEO of the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals (TORCH).

“There are four or five rural hospitals right now that I’m worried about where they say they don’t know if they’ll make it through another pay cycle,” he said.

When rural hospitals struggle financially, they frequently shut down obstetric services to save money, Mr. Henderson says. Of the 26 rural Texas hospitals that have closed since 2010, none of them were delivering babies at the time of their closure.

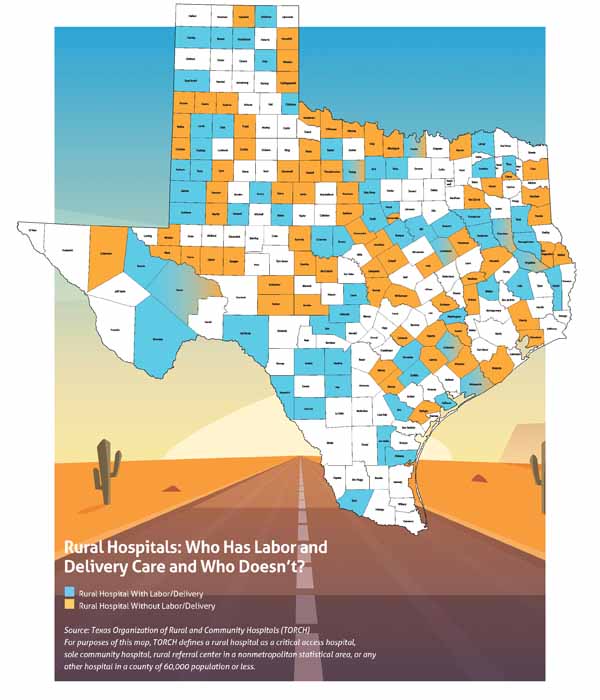

“A generation ago, 60% of rural Texas hospitals provided [obstetric] services and delivered babies,” he said. “Now, that’s flipped where 40% do and 60% don’t.”

The growth in these so-called “maternity deserts” – regions with inadequate or no obstetric care – affects rural counties statewide. But many counties in West Texas and the Panhandle face the biggest challenges because of the vast distances patients must travel. (See “Rural Hospitals: Who Has Labor and Delivery Care and Who Doesn’t?” page 42.)

No rural hospitals closed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Mr. Henderson says. But that was attributable mostly to “federal stimulus dollars and a lot of work.” That aid may not last much longer, meaning the problem of maternity deserts – and other rural health care shortages – is likely to get worse.

“Rural hospitals limped into the pandemic, and they’ll be vulnerable on the other side,” he said.

Shorthanded and shortchanged

Maternity deserts are caused in part by a lack of rural physicians, Dr. Liedtke says. Physicians typically train in big cities, and they enjoy big-city medical resources and an urban lifestyle, so most are reluctant to move to rural areas, she says. The fact that many rural hospitals struggle financially does not help.

“We’ve been trying to recruit an [obstetrician-gynecologist] to our hospital [in Sweetwater] for almost five years and haven’t been able to get one,” Dr. Liedtke said. “Recruiting to rural places is a tough job in itself.” (See “Rural Residencies,” December 2018 Texas Medicine, pages 32-37, www.texmed.org/RuralResidencies.)

But the more immediate causes of Texas’ spreading maternity deserts are a lack of qualified nursing care and financial problems tied to Medicaid, Mr. Henderson says.

Like physicians, nurses were in short supply before the COVID-19 pandemic began in the U.S. in March 2020. Since then, the demand for nurses swelled, prompting many nurses to move to new jobs with higher salaries.

The lack of nurses has hit hard in Alpine, a small town about 90 miles north of Big Bend National Park in West Texas, says Adrian Billings, MD, a family physician and one of five physicians in the area who delivers babies.

In July 2021, Big Bend Regional Medical Center, the region’s 25-bed critical care facility, announced it would have to stop delivering babies from Thursday morning to Monday morning each week because of a lack of labor and delivery nurses. The hospital serves a 12,000-square-mile area with a population of about 25,000, Dr. Billings says.

Since then, the hospital’s medical-surgical unit, laboratory, and radiology departments all have faced workforce shortages, prompting patients to be diverted elsewhere at times, Dr. Billings says. When the labor and delivery unit is closed, all births have to be done in the emergency department if the patient is unable to be transferred to one of the distant labor and delivery units in Fort Stockton, Odessa, or El Paso.

“It is certainly a different experience delivering a baby in an emergency room versus delivering them in a labor and delivery unit with skilled labor and delivery nurses,” he said. “In my view, we’re not able to provide the standard of care in the emergency room when we have to deliver these women.”

The hospital’s partial closure of the unit forces women to make dangerous choices, Dr. Billings says. On a recent Friday night, a woman who was 41 weeks pregnant came into the emergency department with clear symptoms of preeclampsia as well as other problems. The labor and delivery unit was closed, and no air or ground ambulance could transport her for hours. Her best hope for effective health care was to make a two-hour drive to a hospital in Odessa.

“This woman made the very difficult decision to get in a private vehicle and hope that she didn’t become eclamptic on the drive there,” Dr. Billings said.

Two days later, he had another patient with similar problems who had to make the same choice.

“Our biggest fear is that we’re about to have a hospital close out here in this incredibly vast, remote, under-resourced area,” he said. “We have a lot of tourists who come down here to vacation at Big Bend National Park, and they probably have no idea of the significant limitations that we’re facing from a medical standpoint.”

Those limitations have been fed by low payments from Texas Medicaid. In many rural hospitals, most of the patients rely on the program. For instance, Dr. Liedtke estimates that about 70% of patients at the Sweetwater hospital are on Medicaid.

“A lot of [the problem of maternity deserts] is reimbursement pressure, because a lot of those are Medicaid deliveries, and they don’t pay great,” Mr. Henderson said.

The Texas Legislature eased some of the pressure on rural hospitals in 2019 by allotting extra Medicaid money for obstetric services, he says. Although that money did not reopen any obstetric services, it helped stabilize those headed for financial trouble.

However, the Texas Legislature so far has refused to consider most efforts to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, a move supported by TMA. If Texas were to expand Medicaid, an estimated 1.7 million uninsured – of the state’s nation-leading 5 million uninsured – would be newly eligible for coverage, according to healthcare.gov.

In 2021, Texas lawmakers made an exception by extending Medicaid postpartum coverage from two months to six months. TMA continues to advocate for expanding that coverage to 12 months postpartum.

Both the Texas House of Representatives and the Texas Senate are studying legislation designed to improve access to health care for the legislative session that will begin in January 2023.

Maternity deserts also defy short-term solutions that don’t involve greater funding, Mr. Henderson says.

Telemedicine has been a useful tool in helping physicians reach out to far-flung patients in rural areas. But telemedicine does not help with delivering babies, and – in Dr. Liedtke’s experience – so far has proved of limited value even with regular maternal checkups.

“We tried to do it with maternal-fetal medicine for a little while, but we just didn’t have a great response to it from our patients,” she said. “At least in West Texas, they want to connect with their doctor, and they want them to lay hands on them.”

However, telehealth remains one of the strategies used to help improve maternal and infant care in rural areas. For instance, telehealth is a key tool for the experimental Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies (RMOMS) program run by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, which coordinates the efforts of several health care systems in a six-county area of Southwest Texas (Edwards, Kinney, Real, Uvalde, Val Verde, and Zavala counties).

RMOMS also aims to improve maternal and infant care by recruiting more staff, improving perinatal case management, and developing better ways to help patients navigate the health care system (tma.tips/RMOMS).

Many patients in border areas tire of the problems they face getting health care in Texas and drive to equally rural parts of Mexico to obtain care, Dr. Billings says.

“To me, that seems unjust that a U.S. citizen has to rely on the Mexican health care system because the Texas health care system out here is at times inadequate, so far away, and so limited,” he said.

Texas already has medical education programs designed to boost the number of physicians and other health care professionals working in rural areas. But the state needs to take a long-term approach and expand those programs and create new ones to improve the Texas rural health care workforce, Dr. Billings says.

The most successful rural training programs nationally encourage young people growing up in rural areas to go into medical fields, and then they nourish their careers, he says.

“Rural-raised students are the ones who have families here, who grew up here, who have roots here. They’re the ones who have relationships with their community members, who are most likely to return when they finish their nursing school or dental school or medical school,” he said. “Without a significant investment in rural health workforce education, our rural health disparities and health outcomes will only continue to worsen.”

Tex Med. 2022;118(6):40-43

June 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page