When Tina Philip, DO, joined the Texas Medical Association as a medical student in the early 2000s, she was outnumbered. Women made up less than 25% of TMA’s ranks at the time, and she was one of few women serving on the association’s Committee on Membership. She wondered whether to stick around given the lack of representation of people like her: young and female.

“It was definitely a different demographic, and it just felt awkward,” Dr. Philip said.

Since then, however, she has observed a sea change in organized medicine. She participated in TMA’s Leadership College, which offers training for young physicians, and rose through the ranks of the membership committee, eventually serving as chair. By then, so many women were serving on the committee that she had to focus her recruiting efforts on men to ensure balance. She also became involved in the Travis County Medical Society and championed the eventual creation of a TMA Women Physicians Section in 2019.

Thanks in part to this leadership experience and to connections made through TMA, Dr. Philip felt confident enough to open her own family medicine practice in Round Rock in March 2020. In addition to becoming a small business owner in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic, she was elected chair of the Women Physicians Section and welcomed her third child.

Dr. Philip acknowledges the progress made over the course of her career, but she believes there is more work to be done.

“One of my biggest goals [as chair] is getting more females into leadership because the truth of the matter is: There’s so much untapped potential in female physicians in this state,” she said.

Although medicine remains a predominantly male profession, women physicians are growing in number and influence.

In Texas, women accounted for 36% of active physicians as of September, just under the national rate of 37% and more than double their share 25 years ago. They now outnumber men among Texas medical school enrollees, suggesting they may account for most of the physician workforce in future decades. (See “Flooding a Leaky Pipeline,” page 22.)

In addition, for the past two years, TMA’s House of Delegates has elected a woman to serve as the association president, and three women served as president of the American Medical Association consecutively from 2018 to 2020.

Medicine generally embraces these changing demographics. TMA past President David C. Fleeger, MD, oversaw the formation of the Women Physicians Section during his 2019-20 tenure. He says it’s a good thing that the gender ratio of medical school graduates increasingly reflects that of the general population, which is close to equal.

But women physicians still face obstacles, including the gender wage gap, sexual harassment, and a lack of leadership opportunities, which have prompted some to leave medicine. This is critical for Texans as the state faces a worsening physician shortage. For others, however, these barriers have mobilized them to improve the profession they inherited, for themselves and future generations.

It will take time to achieve gender parity along every inch of the physician pipeline. But medical students like Swetha Maddipudi, a fourth-year student at the Long School of Medicine at UT Health San Antonio, are already reaping its rewards. She represents TMA’s Medical Student Section on the Board of Trustees; the section advocates for gender equity in medicine through resolution writing and other advocacy work.

“Knowing that, at each stage from here on forward, I’m always going to have that support around me is really important,” Ms. Maddipudi said.

A leaky pipeline

Although women are flooding into medical schools, they are in the minority at the higher levels of the profession, where gender parity remains something of a pipe dream.

Among women who self-identify as holding a leadership position, fewer than 10% report being a department chair, CEO, or chief medical officer, according to AMA’s Women Physicians Section. And these disparities carry over into academic medicine.

The source of this leak is multifold. Besides pay inequities and sexual harassment, women physicians struggle with other unique challenges like inadequate family leave policies and implicit bias in the workplace. As in other professions, women physicians also do the bulk of domestic work.

“I found the pressures that we experienced were very different than the guys’,” Temple gastroenterologist Dawn Sears, MD, said, citing fertility issues, breastfeeding, and menopause, among others.

On top of balancing her work and family, Dr. Sears struggled to respond to the growing number of female colleagues looking for advice about child care and implicit bias, such as when patients mistake them for nonphysicians. Although she is passionate about increasing the number of women physicians at all levels, she didn’t have the bandwidth to take on these mentorship requests.

“I’ve got three kids of my own, I have nine fellows, and I run my own division,” she explained.

For these reasons and more, women physicians are at higher risk of experiencing burnout and less likely to recommend medicine as a career to others. Research shows they are more likely than their male colleagues to scale back to part-time work or leave medicine entirely because of family demands, according to a 2019 JAMA Network Open study (tma.tips/GenderDisparities).

“You get people who feel so burnt out that they need to leave,” said Susan A. Matulevicius, MD, assistant dean of faculty wellness at UT Southwestern Medical Center, lead author of the JAMA study, and a participant in TMA’s Women Physicians Section. “It worsens the inequities at higher levels of leadership.”

Dr. Matulevicius argues that women physicians are both more likely to be affected by these leaks and better equipped to seal them. “From a gender perspective, the goal is to get more women in leadership because they can bring those issues to light,” she said.

Getting organized

Aware of these issues and keen to address them, TMA began exploring the creation of a Women Physicians Section in 2018. In the past, women physicians had rejected such a section, worried it would further silo them. But attitudes changed, especially in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

“There’s some validity to that [silo concern], but at the same time, we’re not the same [as male physicians],” Dr. Philip said. “We don’t all have the same issues or the same obstacles that are affecting us day to day.”

There were other motivations. A TMA survey found lower membership and engagement rates among women physicians. As a result, the association began hosting events specifically for women in medicine, which were well attended and demonstrated interest in a dedicated section.

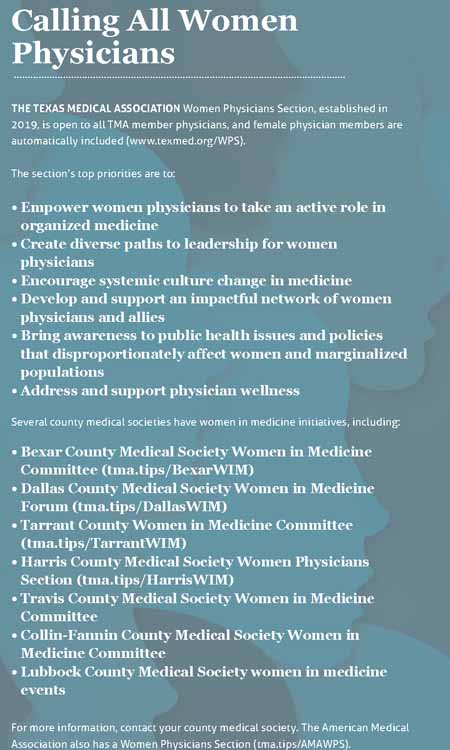

In May 2019, TMA’s House of Delegates approved the creation of the Women Physicians Section, which helps develop policy, programming, and services to ensure women are well represented within organized medicine. All female TMA members are automatically in the section, which is also open to men. (See “Calling All Women Physicians,” page 19.)

The section developed a list of priorities, which include increasing the number of women involved in organized medicine; supporting mentorship and sponsorship opportunities; and advocating for seismic policy changes, such as gender pay parity and paid parental leave. Their mission was nothing short of changing the culture of medicine.

“In the past, so much of the focus was on fixing the women,” said Elizabeth M. Rebello, MD, a Houston anesthesiologist and the section’s inaugural chair. “But really the focus needs to be fixing the system.”

For example, TMA’s Women Physicians Section has since drafted a resolution in support of paid parental leave at the private, local, state, and federal levels, which the House of Delegates referred for study at TexMed 2021 in May.

The section also has hosted a series of events, including one that focused on personal safety after the January shooting death of Austin pediatrician Lindley Dodson, MD, who was taken hostage at the clinic where she worked.

The executive council works hard to ensure section programming is timely, relevant, and meaningful. “It’s got to be pretty important for women to take time away from those other priorities,” Dr. Philip said.

This approach is paying off with improved engagement rates: Women physicians have attended events in droves and provided positive feedback. Between April 2018 and April 2020, the percentage of female members participating in TMA increased 6.2%, according to TMA research.

Although the Women Physicians Section is obviously focused on women, men also play an important role in achieving its goals, especially those related to increasing the number of women physicians in leadership positions. Male leaders can help recognize talented female colleagues, serve as mentors, and provide opportunities for them to earn more visibility and status.

“It’s really a combined effort,” Dr. Rebello said. “Women cannot do this by themselves.”

The pandemic effect

TMA’s Women Physicians Section was formed shortly before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has both exacerbated the challenges its members face and offered some potential solutions, such as more flexible work environments.

Dr. Matulevicius led a survey of 1,186 medical, graduate, and health professional school faculty at UT Southwestern Medical Center after the onset of the pandemic. The results show that female faculty with children were more likely to consider leaving the profession than they were before the pandemic. “There’s only 24 hours in a day, and when you have to fit in the responsibilities of caring for someone else in addition to the responsibilities of caring for your patients, it’s a hard balance,” she said.

The public health emergency also coincided with critical staffing shortages. With no slack in the workforce, physicians and other health care professionals felt less able to take time off to care for their families or attend to burnout because there may not have been anyone to cover for them.

“When there’s that conflict, it’s just an awful place to be when you know your patients need you but so does your kid,” Dr. Matulevicius said.

On the other hand, the pandemic also ushered in the age of telemedicine, which affords physicians more flexibility, and catalyzed workplace policy changes.

Armed with the study’s findings, UT Southwestern recently increased benefits, including a nanny-vetting service and free membership to a sitter database; created a private social media group for faculty to foster community; and started connecting new parents to a licensed clinical social worker for three months after the arrival of a child, which is when many faculty members choose to scale back their work hours or leave medicine.

Such interventions benefit not only women physicians but also their employers and patients.

Replacing a physician can cost a health system anywhere between $200,000 to $1 million, according to a 2016 report by B.E. Smith/AMN Healthcare, a health care staffing company.

The loss of any physician – to another field, early retirement, or death – is disastrous for Texans. The state’s physician shortage is expected to grow to 10,330 by 2032, up from 6,218 in 2018, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services.

TMA’s Women Physicians Section, along with similar efforts at the local and national levels, are working to prevent this outcome. Dr. Sears, the Temple gastroenterologist, recently received a grant from the TMA Foundation to create a women physician health and wellness program for Bell County Medical Society members. She also recently started her own physician coaching and consulting business, GutGirlMD.

“This is a huge [return on investment],” she said. “When you keep a woman physician, you’re going to save $200,000 minimum for every physician you keep from quitting or going part-time.”

The pandemic has also spurred discussions about work-life balance among Ms. Maddipudi and her medical school classmates, who completed their clinical rotations in its midst and saw firsthand how hard physicians were working. She says the experience has made her think more about the support systems residency programs can offer.

Ms. Maddipudi’s classmates are mostly women, and she’s already connected with women physician mentors, who have provided advice on specialty choice, what to look for in a residency program’s benefits, and how to negotiate one’s salary as an attending.

“It’s exciting to think that, when I enter my career as a fully trained physician, I could be working alongside people who’ve had similar experiences, where in the past – probably two or three decades ago – that would not be the case for a new attending,” she said.

Tex Med. 2021;117(12):16-21

December 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page