“All health care is local” is a credo that physicians like Dallas internist Sue Bornstein, MD, live by. That goes for addressing social disparities in health and health care, too.

Which is why an accountable health organization (AHO) is such a promising concept for tackling social determinants of health – the many nonmedical factors in patients’ environments that also influence their health. (See “Healthy Determination,” page 16.)

The Texas Medical Association was in the process of developing and promoting the AHO concept before the COVID-19 pandemic hit and is doing so in earnest this year as Texas looks forward to a post-pandemic future.

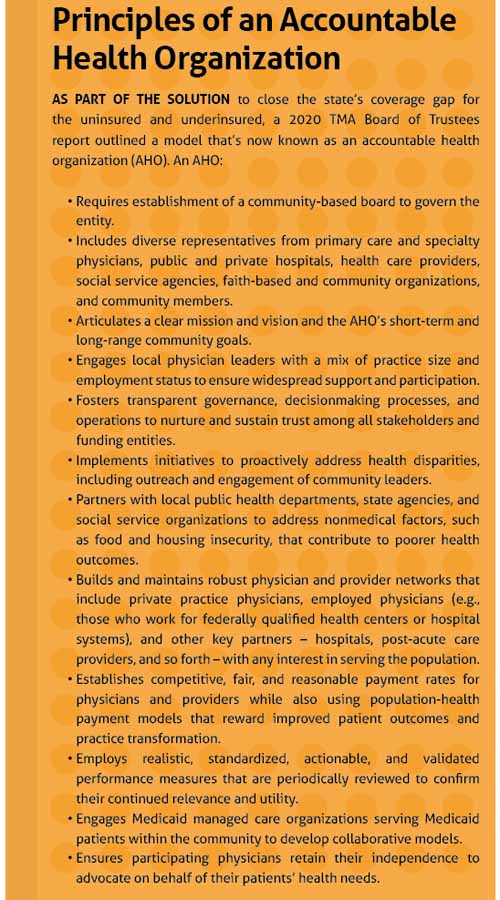

AHOs organize both caregiving and noncaregiving components of the health care delivery system, governed by a community-based board of physicians, hospitals, safety-net entities, social support organizations, and others. The AHO would collaborate on a locally tailored approach to improve vulnerable patients’ access to care and promote innovative initiatives to improve population health and support value-based care.

The AHO itself would not deliver care but would work with those who do to establish a common vision, purpose, and direction for addressing health care quality, safety, and equity for the community. Ultimately, its aim is to foster local decisions regarding how best to improve access to care, health outcomes, and health equity, and to reduce costs. Other states and localities have established similar models.

Many aspects of the AHO concept are different from approaches that have come before it, says Dr. Bornstein, executive director of the Texas Primary Care Consortium and a member of TMA’s Board of Trustees. For one, the community-based board would include nonmedical community organizations, such as food banks, housing support entities, and insurers – a “broad-based representation of people that are involved in providing access to care for people,” she said.

“I will tell you, it’s an audacious thing in a lot of ways,” Dr. Bornstein added. “A lot of the reason why is because it’s never been done [in Texas] like this before. [Right now, organizations] have their own role. The Medicaid MCOs (managed care organizations), they have their own role and they each do their own thing. A lot of them do great work, but there’s not really a commonality.”

Having all those groups at the table can allow a community to standardize and coordinate its approach to combating social disparities, she said.

“Let’s say that … as an example, Superior Health [Plan] has their own approach to hunger in their beneficiaries, and so does Amerigroup; they have their own way of dealing with access to food for people who don’t have [it]. Wouldn’t it be a great idea if we could standardize that and say, ‘This is the process that we need if you’re screening through your practice, if you identify an individual or family that has food insecurity, this is the process that you should follow.’

“We believe that standardizing those kind of processes will be easier for [those] providing care. Because one of the things we hear a lot is this lack of harmonization of processes and procedures, whether that’s in care or measures or processes. That is a really important part of it.”

TMA wrote in a 2020 Board of Trustees report that what’s now called an AHO model, when implemented with physician leadership, “can provide a seamless network of physician practices, inclusive of the full spectrum of primary and specialty care, enabling greater access to health care for low-income and uninsured individuals.” Principles of an AHO, as laid out in the report, included engaging a professionally diverse group of local physician leaders and fostering transparency.

Jim Walton, DO, was president of the Dallas County Medical Society in 2015 when it began developing what became the AHO model. He believes the transparency aspect is the most important piece to make the concept work – showing where the funds are going.

“What we should be accountable for is working toward reducing or eliminating racial and ethnic health disparities. As we all know, the uninsured population is concentrated in the low-income minority populations in the state of Texas. Our idea, then, is to be transparent with how the [AHO] spends financial resources for improving access and health care delivery to [reduce] inequity,” he said.

Dr. Walton says the local focus also enhances accountability.

“In the [AHO] model, we are accountable to our colleagues, to our neighbors, and the local community where we live – community-based leaders that are monitoring both the processes [and] the outcomes,” Dr. Walton said.

And ultimately, an AHO is a customization of an area’s health care for its unique needs, Dr. Bornstein says.

“This kind of a structure allows for individual communities to really tailor their services and their focus and their resources to the people in their community,” she said. “And that’s kind of the novel part of it, is that every community is different. … Yes, there are some overarching needs. But each community has its own challenges.”

Prior to the pandemic, TMA pitched the AHO concept to the state as a potential cost-efficient pilot program to test alternative ways to organize local safety-net health care systems, whether or not Texas received an extension on its federal Medicaid 1115 Transformation Waiver – set to expire in September 2022.

At press time, TMA was providing input to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) as it prepared to apply for an extension. TMA, along with state specialty societies and think tanks, submitted comments urging HHSC to include an AHO pilot in its waiver request.

Tex Med. 2021;117(9):34-35

September 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page