Barriers stand in the way of physicians playing a greater role in addressing the social determinants of health, but awareness of those factors is increasing, and progress is happening.

Some Texas physicians are already pros at screening and referring patients for help overcoming food insecurity, lack of transportation, and other social determinants impacting doctors’ ability to fully address their health needs.

But for many other physicians, helping patients conquer those barriers first requires doctors clearing barriers of their own.

Texas physicians plugged into the evolving study of social disparities say some of those roadblocks are the same factors that plague medical practice today in other ways: lack of time and adequate payment, and unfamiliarity with screening tools and other aspects of social determinants that they weren’t taught in medical school.

Meanwhile, a certain skepticism among lawmakers about the right way to tackle social determinants prevented Texas Medical Association-supported legislation from moving forward during the regular 2021 session of the Texas Legislature.

The good news is, with the pandemic shining a light on the disproportionate impact of social determinants on certain populations, payers and lawmakers are coming around to recognizing the need for identifying and addressing these factors and their impact on not only patients’ health but also costs. And the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) is using federal funds to specifically address COVID-19 health disparities among high-risk and underserved populations through a renamed office under DSHS.

“Physicians alone can’t fix this, and so it is going to take a team approach and realizing that we need to work with other health professionals and people on a team to be able to create the resources that our patients need to overcome these,” said Houston family physician Lindsay Botsford, MD. “That does take a degree of humility on the part of us as physicians to realize that we can’t fix it all ourselves, and that controlling someone’s diabetes may be more than figuring out the perfect medication regimen – more about figuring out how to get them reliable access to healthy food and other things like that.”

Time and money

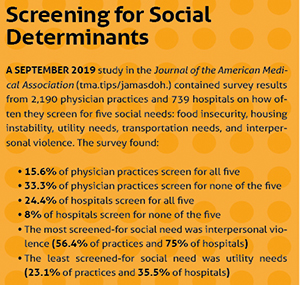

If a September 2019 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association is any indication, physicians and hospitals that comprehensively screen for social determinants are a minority. And TMA staff say of those physicians who screen, very few refer the patient to social services that can help them with social determinants. (See “Screening for Social Determinants,” right.)

Texas physicians say the reasons why their colleagues aren’t screening are varied. But Dallas internist Jim Walton, DO, stresses that it’s not a lack of belief in the scientific validity of social determinants. He says the pandemic’s disproportionate morbidity and mortality impact on people of color and people in a low socioeconomic status have shed a light on social health factors.

“Most physicians from the very beginning of medical school and their training embrace that … concept of a holistic approach to the health of patients,” said Dr. Walton, CEO of Genesis Physicians Group. “There is a practical reality of the science of health and the practical reality of practicing medicine in the complex world we live and the requirements, if you will, of the payer community.”

One of those realities is the prospect of adding to physicians’ existing bureaucratic burdens with a social disparity screening process, without financial incentives that make it worthwhile, Dr. Walton says. For example, physicians who treat Medicaid patients – for whom social disparities often come into play – are already doing so at depressed, static payment rates.

Going hand in hand with that factor is what Dr. Botsford calls the No. 1 reason: Time. Doctors just don’t have enough. Her practice screens all new patients for social determinants and works with a behavioral health specialist to link up patients with the resources to address them. While implementing those screening tools has been easier than expected, she says the time required has still made it a considerable challenge.

“In our population, we care for older adults, and especially as we take on new patients in our practice, they are coming in with complex medical needs. Sometimes it feels like there’s so much to do,” she said. “The barrier of time is so real, and I don’t know that we’ve totally overcome that.”

Other factors standing between some physicians and a role in combating social disparities, Dr. Botsford says, include unfamiliarity with screening tools and the lack of a team around the physician to help with the effort.

“Sometimes, clinicians feel defeated in even asking about it because of a lack of belief that they have the tools to be able to do something about it,” she said.

TMA Associate Vice President of Governmental Affairs Helen Kent Davis says a lack of community infrastructure to connect patients to resources is another barrier. (See “Creative Collaboration,” page 24.)

“If a physician screens for food insecurity, they then need to know where to refer patients for assistance,” she said. “Most communities do not have a cohesive mechanism for physicians to connect easily to these resources.”

Skepticism at the Capitol

Can the team effort to help patients overcome social disparities include involvement from state government? During this year’s regular legislative session, Rep. Tom Oliverson, MD (R-Cypress), ran into some sentiment that it couldn’t, and that skepticism from lawmakers proved to be another barrier, even among lawmakers who fully acknowledge how determinant social factors can be.

Representative Oliverson authored the TMA-supported House Bill 4365, which would have required the state to pursue a five-year Medicaid pilot program to provide “enhanced case management and other coordinated, evidence-based, nonmedical intervention services” designed to address five specific social determinants: housing instability, food insecurity, transportation insecurity, interpersonal violence, and toxic stress. HB 4365 never made it out of committee.

“The Catch-22 with this issue is that there were many that were not convinced that government, or that even the Medicaid managed care [organizations] … would spend these dollars wisely,” Representative Oliverson told Texas Medicine.

“At least what I was hearing from some members is ‘We agree with the science, but we’re concerned about the implementation,’” he added. “It’s very easy to pay doctors to see patients. It’s very easy to measure outcomes. But when we start talking about things like housing insecurity, how do we measure outcomes?”

He envisions resurrecting the pilot program bill during the 2023 legislative session. “This is about innovation.”

North Carolina’s Department of Health and Human Services announced in June that it was embarking on three Medicaid pilot programs related to social determinants of health, and Ms. Davis says other states have implemented similar models as well.

Another bill that could have leveraged state resources to attack social disparities had more luck but still didn’t pass. Rep. Garnet Coleman (D-Houston) authored TMA-supported House Bill 4139, which would have created a state Office for Health Equity. HB 4139 passed the House but went nowhere in the Senate.

Making headway

However, there are signs of progress on several fronts. Payers say they’re doing their part.

For example, UnitedHealthcare (UHC) is working both within the company and with physicians and community-based organizations, Salil Deshpande, MD, the Medicaid-focused chief medical officer of UHC’s Community Plan of Texas, told Texas Medicine. Among those initiatives, he says UHC worked with the American Medical Association and others to advocate for expansion of ICD-10 social determinant codes, and some new codes are going into effect Oct. 1.

Amerigroup, a Medicaid managed care company, tells Texas Medicine it offers a social-determinants incentive program in the Lone Star State and other markets that pays for screening, referral, billing the right diagnosis codes, and following up to see if the patient sought help after the referral. Amerigroup offers contracted physicians access to AuntBertha.org, one of the leading social-determinant screening and referral platforms. (See “Resources,” page 28.) It also has kiosks at some offices and community centers where patients can complete social-determinant assessments themselves.

Greg Thompson, president of Amerigroup’s Texas Plan, said the insurer is mindful of physicians’ administrative burden when it comes to integrating social determinants in their workflow; in fact, that’s why it created the incentive program.

“We wanted to be able to financially compensate the physicians for completing these services that will help our members,” he said. “We provide support to the physicians to help address any barriers they are encountering as well to help try to solve or streamline those issues.”

Overall, progress is happening, Dr. Deshpande says, although it feels a little slow-going due in part to the pandemic dominating the health care system’s attention since early 2020.

“In fact, I would say that we see a greater amount of interest and participation in our learning collaboratives and other related efforts now than I would say two or three years ago,” he said. “It’s hard to know whether that greater interest and that progress is coming just because there’s a greater understanding over time, or to some extent, I think a lot of communities that we serve have been profoundly impacted over the last year and a half by the pandemic, by the loss of economic opportunities, by other things. Maybe some of their social [factors] have even worsened over the last couple of years, so maybe that has spurred the health care provider community to pay a little bit more attention.”

Meanwhile, DSHS is putting $45 million in funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) toward refocusing an existing DSHS office, and deploying existing public health experts, to address some of the problem.

The Office of Health Equity Policy and Performance – formerly the Office of Public Health Policy and Performance – will use the money to “engage targeted communities disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and build sustainable relationships in those targeted communities leading to improved health among vulnerable populations,” according to a DSHS PowerPoint on the renamed office. The funding came from a CDC grant program to address COVID-19 health disparities. DSHS told Houston Public Radio the office had no connection to HB 4139, the failed Office for Health Equity bill.

Clearing the way for more effective social-disparity work in medicine is difficult, Dr. Botsford says. But she adds that value-based models – where “we certainly can think about what’s right for the patients and less concerned about how we bill for that” – are giving physicians more practice freedom to incorporate social determinants. In traditional fee-or-service setups, she says, it’s more difficult to do so.

“Physicians may, in the end, see better outcomes for their patients in terms of quality scores or other things like that, and certainly potentially lower hospital admissions,” she said. “But it’s a long game, and that’s just not the way that physicians are rewarded or incentivized in most payment models in [their] current state.”

Now that the pandemic has shed light on social determinants and whom they impact, Dr. Walton adds, it’s incumbent on medicine to “press in further” to make its own impact.

Tex Med. 2021;117(9):30-33

September 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page