U.S. children usually visit a physician on a set schedule through their teen years. COVID-19 made a mess of that schedule, and Texas physicians are trying to help families address the health care fallout before school starts again in the fall.

After the pandemic arrived in Texas in March 2020, pediatricians and other family physicians reported to the Texas Medical Association that the number of well-child visits dropped dramatically. (See “On Pause for the Pandemic,” July 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 22-28, www.texmed.org/PandemicPause.)

“We did not see any children over the age of 2 years for well visits for a couple of months in the early part of the pandemic,” said Keller pediatrician Jason Terk, MD. “It was absolutely a falling off a cliff.”

Well-child visits allow pediatricians and family physicians to check growth and developmental milestones, provide anticipatory guidance on health and safety priorities, and address any chronic health problems that exist or are emerging, he says.

In the wake of COVID-19, that can include problems caused by the pandemic, such as lung damage caused by the disease itself or increased levels of depression caused by months of social isolation, says Tyler pediatrician Valerie Smith, MD, who sits on TMA’s Council on Science and Public Health.

But physicians’ biggest concern remains routine vaccinations for childhood disease like measles, mumps, and whooping cough, she says.

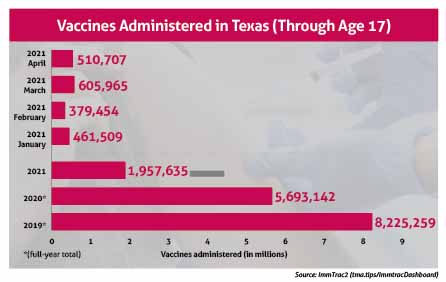

The number of recorded vaccines administered in 2020 in Texas dropped sharply according to

ImmTrac2, the state’s vaccine registry, which is administered by the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS). (See “Vaccines Administered in Texas.")

Once COVID-19 vaccines became widely available in early 2021, the number of childhood vaccines given each month started to rebound in March 2021, exceeding year-to-date 2020 levels, the data show. But this year’s vaccination levels still do not match 2019’s.

“I pretty much don’t spend a day in clinic now when I’m not seeing a child who is behind in vaccinations,” Dr. Smith said.

Even before the pandemic, Texas vaccine rates needed improvement, data shows. For instance, Texas already lagged behind the rest of the country in vaccinations for human papillomavirus (HPV).

In 2019, Texas ranked 41 out of 50 states and Washington, D.C., for HPV vaccine rates among children aged 13 to 17, the American Cancer Society reported. And HPV vaccinations nationwide declined by more than 20%, over 1 million doses, compared with before the pandemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Texas also permits an increasing number of children to opt out of childhood vaccines. In 2003, the Texas Legislature allowed parents to obtain nonmedical exemptions from public school vaccines for their children. Since then, statewide nonmedical exemptions have jumped from 2,314 in the 2003-04 school year to 72,743 in the 2019-20 school year, according to DSHS.

TMA has opposed these exemptions, and the 2021 House of Delegates approved a resolution that called for advocating for the removal of nonmedical exemptions from vaccinations approved and recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The DSHS numbers don’t reflect the entire problem, says Peter Hotez, MD, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development.

Speaking at the General Session of TexMed 2021, Dr. Hotez told Texas physicians that the true number of unvaccinated children is probably over 100,000 because the DSHS exemption data does not include any of the state’s 350,000 homeschooled children.

Also, many of those unvaccinated children are clustered in “hotspots” full of similarly unvaccinated people that are ripe for disease outbreaks, he says (www.texmed.org/2019Texashotspots).

“A lot of this is centered around the suburbs of Austin and but also North Texas – Plano, Denton, Fort Worth,” he said. “It’s pretty bad there as well. This has become now a public health problem.”

Active recall

Physicians can help counter these and other health problems caused by the pandemic by ensuring that patients know the importance of getting well-checks, says Frisco pediatrician Seth Kaplan, MD, president of the Texas Pediatric Society.

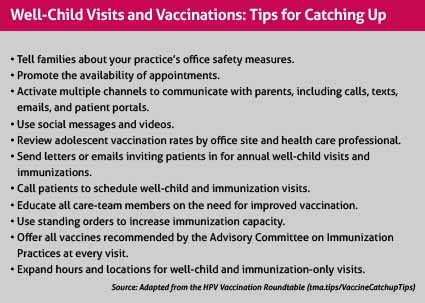

Physicians routinely work to get patients back to the office, but this year those efforts should be more intense, Dr. Kaplan says. His office has been extremely aggressive about recall efforts to reach out to patients who have not come back recently or who have conditions that need addressing, he says. (See “Well-Child Visits and Vaccinations: Tips for Catching Up,” page 42.)

“Especially, in the teen population, if you’re not actively doing that recall, a lot of them fall behind because if they think everything’s going great and they’ve got no concerns and don’t know they’re due for any vaccines, they just don’t come in,” he said.

Scheduling changes also can help improve the number of well-child visits, Dr. Smith says.

Since the first of the year, her practice has become gradually busier and now books appointments far in advance. However, the practice – which has two physicians and an advanced practice registered nurse – has made well-child visits a priority by devoting about 85% of one pediatrician’s time to them. Normally, both physicians would schedule half well-visits and half sick-visits, she says.

Providing COVID-19 vaccines comes with extra challenges for pediatricians and family practices, Dr. Kaplan says. For instance, parents tend to have more questions than they would about other routine vaccines.

“I have already had parents who ask, ‘I did it for my 17-year-old, but is my 13-year-old too young?’” he said. “You have to be able to give that reassurance.”

DSHS has tried to ease the way for physician practices to provide COVID-19 vaccines for young people, in part by lifting certain restrictions, Dr. Kaplan says. For instance, DSHS changed policy by encouraging physicians and other health care professionals to vaccinate anyone who wants a COVID-19 shot, even if that means opening a new vial for that person without knowing whether all doses will be used.

Many pediatric and family practices still can’t give COVID-19 shots because they don’t have adequate storage or other difficulties, Dr. Smith says. Those practices must come up with a reliable nearby outlet for COVID-19 vaccines – like another practice or the local health department.

“Not everybody who hasn’t been vaccinated yet is vaccine hesitant,” she said. “They just haven’t taken the extra effort it would take to get vaccinated. … So if you can’t provide vaccine in your clinic, you need to come up with a process that allows teenagers and their parents to register and get vaccinated as easily as possible.”

Healing after the pandemic

Pediatricians working with patients who stayed away from their doctor’s office during the pandemic expect to see a variety of health problems beyond vaccination, Dr. Smith says.

Many of those problems are scars caused directly by COVID-19, Dr. Smith says. For instance, physicians doing sports physicals will have to be extra vigilant in looking for kids who – knowingly or unknowingly – had COVID-19. The disease could in rare cases cause heart problems and will definitely keep some young people out of sports because of reduced lung capacity.

And many of those scars from the pandemic will be mental, Dr. Kaplan says.

“A significant subset of kids wasn’t accessing care on a regular basis until everything fell apart,” he said. “Either they were failing out of school, or they were ending up in deep, deep, deep depressions that increased suicidal ideation.”

With families returning to regular medical care, physicians have an opportunity to monitor young people for mental health problems caused by this unusual event, he says.

“If we can keep our adolescents coming in on a regular basis and we do the screening for those issues we’re supposed to be doing, then hopefully we can cut off a lot of those issues at the pass and really unearth them before they become a big deal,” he said.

Physicians also can use the Child Psychiatric Access Network (CPAN), which gives pediatricians and family physicians across Texas free telemedicine-based consultation and training on community psychiatry, Dr. Kaplan says. A pediatrician or family physician caring for a patient with psychiatric needs can call CPAN and typically get professional advice in minutes. (See “Use It or Lose It,” December 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 34-37, www.texmed.org/UseCPAN.)

“So if you need someone [who can help you care] for a transgender 15-year-old who’s depressed, they’re going to be able to point you to the folks in that area,” he said.

Nutrition also became badly neglected during the pandemic, Dr. Kaplan says.

“We’ve seen lots of kids whose body mass indexes have gone through the roof for a whole variety of reasons – a lot less activity when sports weren’t happening, being at home for school, having access to the pantry at all times, and just using food as way of alleviating boredom,” he said.

Long-term, this could lead to serious obesity-related health problems. (See “Weighing the Cost of Obesity,” July 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 38-41, www.texmed.org/CostOfObesity.) But physicians have to handle the problem gently without shaming young people. That can start by encouraging more light activity or easy changes in diet.

“We have to approach that with a little bit of grace,” he said. “[Suggest] one or two changes they can make to gradually bring things back to the right place.”

Tex Med. 2021;117(7):40-43

July 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page