Texas opened two new medical schools in July – the University of Houston College of Medicine in Houston and Sam Houston State University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Conroe. Thanks to COVID-19, both opened under circumstances that would have seemed bizarre just a year ago.

Many – but not all – classes are online, and students are deliberately kept from interacting any more than necessary. Both schools held traditional white coat ceremonies to kick off their first class, and both affairs had plenty of masked faces but no parents, friends, or family.

“There’s so much exuberance, joy, and celebration at a new school, and so it was very muted for us because we were all remote,” said Kathryn Horn, MD, associate dean for student affairs, admissions, and outreach at the University of Houston.

And yet students understand the inconveniences caused by the pandemic are temporary, and for the most part, they have learned to roll with them, says Brianna Gonzalez, a first-year student at the University of Houston.

“Now, it’s my normal,” she said of the adjustments to the pandemic. “It’s definitely less [normal] than what we were experiencing in [most of] college, of course, but I don’t feel as fatigued as I felt in March where you were literally isolated at home.”

Like all educational institutions, both schools had to tear up their operation plans and start over when the pandemic hit in the spring. Both sent staff to work from home and looked for ways to anticipate every contingency.

“We wanted to open in person,” Dr. Horn said. “We had a plan A, B, and C because you weren’t sure what was going to happen with COVID. And we ended up pivoting at the very last moment – because numbers [of COVID-19 cases] were surging in Houston – to a completely virtual orientation, which is so different from many medical schools and definitely for a new school.”

Sam Houston State preserved some face-to-face learning, though many of its classes are online, says Mari Hopper, PhD, associate dean for biomedical sciences. Right now, the priority is making sure students are educated despite the unusual atmosphere, not celebrating all the hard work that went into opening a new school.

“We can’t wait for the opportunity to truly have our [real] grand opening,” she said. “We have downsized and downshifted [our expectations], meeting learning needs and at the same time mitigating risk.”

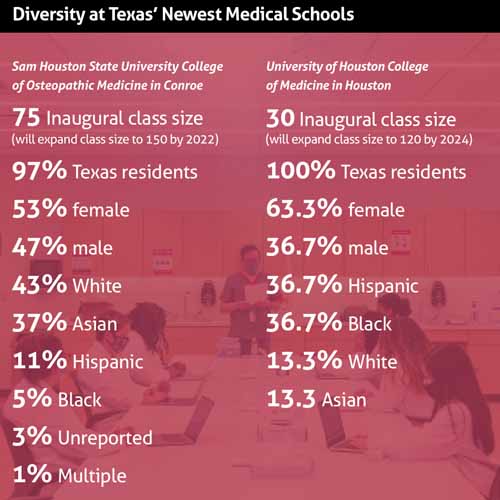

Both Sam Houston State and the University of Houston opened with similar missions – to boost the number of primary care physicians in places where physicians are scarce. The University of Houston aims specifically to bring more of them to urban and rural areas while working to recruit future doctors from underrepresented groups, like Blacks and Latinos. Meanwhile, Sam Houston State’s focus is to improve rural health care, especially in underserved East Texas.

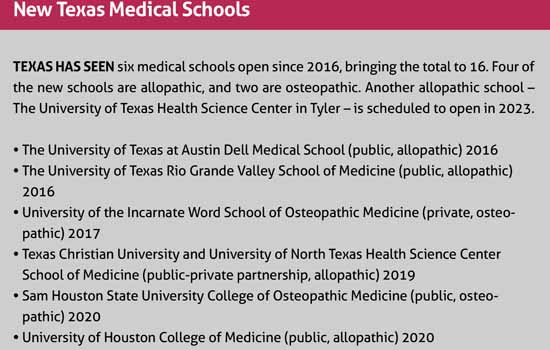

Charles Henley, DO, founding dean at Sam Houston State, points out that Texas is 37th among the 50 states in the number of medical students per capita, so both schools are needed to increase the state’s medical capacity in years to come.

“We need more help,” he said. “We need the ability to actually be able to care for underserved populations. … It takes all the [Texas medical] schools to do that.”

Different approaches

While the two schools share other similarities – they are both state-run schools in the Houston area – they both arrived at opening day in July taking very different paths.

The University of Houston, an allopathic school, followed a traditional route of getting state-approved funding from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB) to launch its College of Medicine.

Currently, Texas pays $46,000 per medical student each year, or $381 million annually, according to state budget data collected by the Texas Medical Association.

The University of Houston College of Medicine received about $20 million in the current state budget, and is expected to receive other state funding, according to Stephen Spann, MD, the school’s founding dean. That money allows it to, among other things, keep tuition in line with the $20,000 average in-state tuition for state-funded medical schools, according to data compiled by TMA.

“But our first class of students is totally on scholarship through four years of medical school because it’s been covered by an anonymous donor, who gave us $3 million,” Dr. Spann said.

Sam Houston State pursued a less orthodox path in several ways. It is just the third osteopathic medical school in Texas, after the University of North Texas Health Science Center Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine in Fort Worth and the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine (UIWSOM), a small private school in San Antonio.

At the time Sam Houston State began planning to create its medical school in 2014, state lawmakers made it clear no state money would be available to fund it, Dr. Henley says. The school nevertheless pressed ahead with an unusual plan – for a state-run medical school in Texas – to fund itself with student tuition.

As a result, Sam Houston State charges about $55,000 per year, Dr. Henley says. That is about the same tuition as private medical schools like UIWSOM.

Most U.S. medical students rely on loans, and 73% graduate with debt, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). The average four-year debt load is $250,222 for public school students and $330,180 for private school students, AAMC says.

Critics of high-tuition medical schools say the debt load incurred by students keeps graduates from choosing primary care positions once they graduate.

But Dr. Henley disagrees, as does AAMC, saying debt is not a large factor in students’ specialty choice (tma.tips/StudentDebtMyth). Nevertheless, Sam Houston State is concerned about student debt and tries to offset tuition costs through scholarships and donations, he says.

Online and in-person

Both schools now use mostly virtual classes, but courses designed to promote interactive problem-solving are still held on campus. For instance, the University of Houston held anatomy classes on campus with small groups, and Sam Houston State conducts small-group lectures designed to have students solve problems on campus. In both cases, masking and social distancing are required.

“The main focus is to be interactive, share questions and concerns,” says Alwyn Mathew, a first-year student at Sam Houston State. “It’s a very collaborative environment.”

Still, its curriculum structure is conventional, Dr. Henley says. It follows the “Flexnarian” model: two years of basic science followed by two years of clinical work.

“We look a lot more like a traditional medical school than you would think,” he said.

Several other new Texas medical schools have experimented with ways to incorporate clinical work in the first two years, and the University of Houston has done that as well, Dr. Spann says. The goal is to get and keep students thinking about primary care.

“Each student spends half a day a week at a primary care clinic throughout the four years of medical school,” he said. “And we have a lot of engagement and partnership with two of our neighboring communities that are underserved.”

Sam Houston State is attractive to medical students in primary care precisely because of its focus on osteopathy, which takes a more holistic approach to treating patients than allopathic medicine, Mr. Mathew says.

“Everything about [a patient’s] environment, about their history, and their family history plays a role in that story for that patient,” he said. “And I see that every time we’re in class.”

Making the ratio

The two new schools also have the shared goal of keeping their medical students in Texas, and developing residency positions is widely considered the best way to do that.

Both Sam Houston State and the University of Houston are subject to Senate Bill 1066, a 2017 state law that requires public medical schools to develop a plan to ensure a sufficient number of residency slots in Texas to reasonably accommodate the schools’ expected number of medical graduates. THECB has set the state’s overall residency target even higher, saying there must be a ratio of 1.1 entry-level residency slots for every Texas medical graduate.

Currently, the state rate is 1.17 to 1, according to TMA data. But unless new residency positions are developed, Texas will slip far below that ratio, and physicians graduating from new Texas medical schools will take positions in other states. Research shows that residents tend to set up practice close to their training programs, so Texas could lose out on recruiting badly needed new physicians. (See “Growing Residents,” June 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 42-45, www.texmed.org/GrowingResidents.)

Dr. Spann is confident the University of Houston will reach the 1.1-to-1 ratio. A partnership with HCA Healthcare in Houston is expected to provide 138 first-year residency slots by the time the school’s first class graduates in 2024.

Sam Houston State has partnerships with hospitals in Beaumont and Lufkin and is scouting others in East Texas, Dr. Henley says. The school still has not nailed down the number of residency positions for its projected graduates. But Dr. Henley is confident it will have the residency positions created by the time its first class graduates.

“We will eventually get there, but it’s not going to be in the first year [of the school’s operation],” he said. “It takes a while to develop and to get it paid for. But we’ve got a real good start.”

Tex Med. 2020;117(2):36-38

February 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page