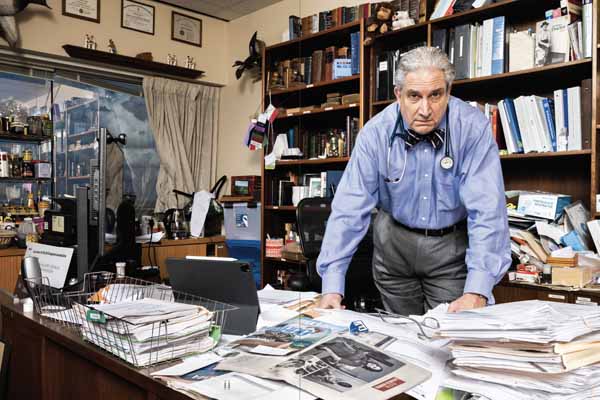

Did you ever hear the parable of the boiled frog?” Robert E. Jackson, MD, asks. Because that’s how the Houston internist views the current path of primary care in Texas.

It’s one of those time-worn fables of unknown origin. In case you’re not familiar, it asserts that if a frog is placed into a pot of boiling water, it will immediately jump out. But if you place the frog in a pot of cool or tepid water, then slowly bring the pot to a boil, the frog won’t sense the danger until it’s too late and will die.

Science quibbles with the tall tale. But the point is, says Dr. Jackson, primary care is in simmering trouble.

Payments are down, with fee-for-service payments an increasingly poor fit for primary care practices; the ranks of Texas’ uninsured and underinsured continue to rise; social disparities in health care persist; and chronic disease continues to cause more death and higher health care costs. And that was before the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing problems while making patients reluctant to go to the doctor, decreasing patient volume and threatening practice viability.

“The path that we’re on is the slow boil to catastrophe,” Dr. Jackson said. “You talk to any primary care doctor, everybody will agree that this is a slow boil. This is not sustainable. It really isn’t.”

The Texas Medical Association and other corners of organized medicine know primary care is part of the bedrock of a sturdy health care system. So medicine – including the Texas Primary Care Consortium (TPCC), of which TMA is a member, and the Texas Academy of Family Physicians (TAFP) – is engaging policymakers to not only help the state’s primary care system survive the pandemic, but also enable it to thrive for the long haul.

Hope abounds that the pandemic has created a moment of political opportunity – that COVID-19 has highlighted primary care’s problems so brightly that lawmakers will be open to backing needed policy changes during the Texas Legislature’s 2021 session.

Pandemic exposes problems

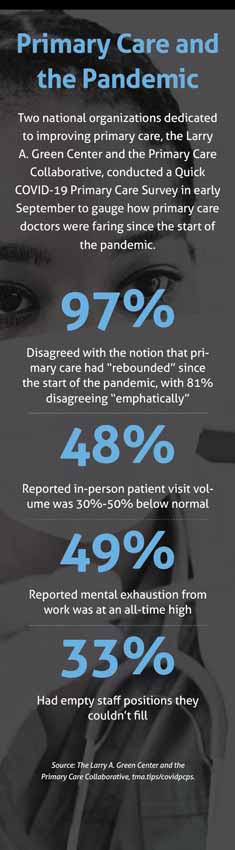

A major part of medicine’s work this past summer was shining a light on the primary care system’s needs. TPCC and TAFP undertook parallel efforts to lay out the system’s problems for policymakers, with both short- and long-term fixes.

The impact of COVID-19 loomed large in both efforts. Rio Grande City family physician Javier Margo Jr., MD, TAFP’s president, says the pandemic made obvious “the fissures and cracks that were already there” in the nation’s health infrastructure.

TAFP, also a member of TPCC, says most primary care practices keep only two months of cash on hand. With many patients staying home instead of going to the doctor, primary care offices immediately faced a touch-and-go outlook.

“It was literally month to month for many of our practices,” Dr. Margo said. “People were furloughed, and even taking advantage of the supplemental amount of assistance we got from the government … you have a bunch of things to do, including keep all your staff on board. A lot of offices were already in the red because of the initial expenses and the lack of patient flow, which was out of necessity, as insurances were figuring out how to pay for virtual visits. That was a big hole where it pretty much ate up most people’s savings. Even here locally, a lot of physicians went without paying themselves.”

In July, TPCC – a statewide effort led by the Texas Medical Home Initiative and the Texas Health Institute – submitted a letter and issue-brief to Texas Gov. Greg Abbott outlining its top concerns about today’s primary care landscape, including:

• Increasing chronic disease burden, which continues to be the health care system’s biggest cost driver;

• Growing uninsured and underinsured populations;

• Growing health disparities, “particularly among people of color and rural communities;” and

• Increasing economic uncertainty.

The issue-brief also asked Governor Abbott and health system leaders to form a statewide panel to “pursue forward-looking primary care and health system transformation efforts in Texas.” For the system’s long-term needs, the consortium recommended the panel:

• Address payment reform;

• Promote a holistic approach in health care delivery by equitably distributing resources;

• Increase access to primary care; and

• Address the growing number of Texas’ uninsured and underinsured.

(See “Recommendations for Reform,” below.)

The consortium also urged federal funding to “provide a targeted allocation to specialties – internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics – that principally provide comprehensive primary care to patients to be sufficient to offset loss of revenue as a result of COVID-19. Failing to do so could lead to the majority of these practices being forced to close, sell to private equity firms, or merge with large consolidated health care systems, thus driving up health care costs and further reducing access to care.”

Released in August, TAFP’s five-point “Marshall Plan” for primary care – which took its name from the U.S. program that helped Western Europe rebuild after World War II – highlighted similar problems and potential solutions:

• Promote comprehensive payment reform and transition away from fee-for-service;

• Use market-based approaches to decreasing the uninsured;

• Accelerate the transition to telemedicine;

• Recalibrate and optimize Texas’ physician workforce; and

• Spot the next pandemic by leveraging primary care for frontline surveillance.

(Read TAFP’s full plan at tma.tips/tafpmarshall.)

Payment reform a must

Payment reform a must

Sue Bornstein, MD, executive director of the Texas Medical Home Initiative, believes the current shift to value-based care is essential to primary care success. People are living longer than they used to, which she calls a “mixed blessing” because they develop more chronic illnesses than patients did decades ago and need more team-based care. So for primary care doctors, fee-for-service payment setups simply don’t work anymore, she told Texas Medicine.

“That model does not really support primary care, because primary care is longitudinal,” she said, referring to a holistic care model that encompasses multiple care sites and episodes of care. “If patients are not able to get in to see their physicians, there’s no money coming in, and … [doctors] can have to close their practices. Whenever we start talking about payment, people are like, ‘Oh, those doctors. They just want their money.’ Well, really, we’re talking about survival here.”

The fee-for-service system, TPCC argues, is designed to focus on a patient’s short-term needs and episodic care, and doesn’t focus on addressing the underlying cause of symptoms or incentivize “coordinating the many health services that an individual with multiple health conditions may require.” But efforts around value-based payments, “including patient and provider-specific prospective payment models,” provide an opportunity for the state, the consortium says, and funding can be used for pilot programs that yield evidence of which approaches work.

The consortium recommended the state collaborate with Texas Medicaid, the Employee Retirement System, and the Teacher Retirement System – the three entities that maintain the bulk of state-regulated health plans – to develop payment models to help sustain primary care practices during the pandemic.

TAFP’s Marshall Plan for primary care similarly advocates for engaging local governments and private employers on so-called prospective payments.

In these models, first established by Medicare, payers make upfront, predetermined payments. TAFP explains that in these systems, physicians generally are paid per patient, instead of per service, and the payments typically are issued at regular intervals, such as per month. Such systems are meant to encourage care efficiency.

The TAFP strategy encourages state-funded health plans and Medicaid to use prospective payments, and urges Texas lawmakers to create a working group to implement a voluntary model for primary care.

“This approach is not new; in fact, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services already uses a prospective payment model in the Medicare program for acute care hospital inpatient stays,” the plan said. “The payment model is one of the hallmarks of success for Medicare Advantage plans. State Medicaid programs, including a handful of managed care organizations in Texas Medicaid, also use prospective capitated payments in managed care.”

TAFP’s plan extensively details the benefits of such models, saying that among primary care practices that fared better during the pandemic, many had previously moved away from fee-for-service.

“It could free [practices] from the churn of seeing patients and allow them to focus their time, energy, and efforts on keeping patients well, and caring for them in the way that makes the most sense for that practice and the physician – whether that’s in person, whether that’s at home, whether that’s virtually, or whether that’s on the phone,” said Tom Banning, TAFP’s executive director. “Unfortunately, our fee-for-service system does not allow for that type of flexibility right now, whereas an alternative payment model or a prospective payment model most certainly would.”

Two of Texas’ largest health insurers, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas and UnitedHealthCare, told Texas Medicine they were unable to comment for this story. The Texas Association of Health Plans did not respond to requests for comment.

TPCC and TAFP acknowledge that implementing such changes and getting health plans on board will not be easy, but say reform is necessary.

“It is a change, and certainly our insurance colleagues have systems in place that, whether it’s accounting or population health, whatever the systems that they have in place, are not really geared for that,” Dr. Bornstein acknowledged. “They’re geared for the transactional type of practice.”

Mr. Banning says TAFP’s focus is “thinking differently about how services are paid for: Make primary care payment based on relational and accessible and continuous care that’s budgetable; and use insurance for what it was intended for,” meaning hospitalization and higher-cost subspecialty care.

Expanding access

The strong correlation between chronic disease burden and social determinants of health is another difficult aspect of the problem for medicine to address, Dr. Bornstein adds.

“Part of the challenge to medicine is to realize that only about 20% to 30% of individuals’ health status has to do with medical status. The rest of it has to do with … where they live, what they eat, the air that they breathe, the water, housing, transportation, all of those things. We have to sort of reallocate our energy,” she said. While it’s not up to doctors to fix those social-determinants of health, “we need to find ways to connect with organizations that can address those needs, or else we’re just going to get deeper in trouble in terms of chronic disease burden.”

For instance, according to TPCC, only 5% to 6% of total health care spending goes to primary care, despite decades of evidence that greater investments in primary care yield healthier populations and lower health spending per capita. On the other hand, “designed with consumer needs and preferences in mind, the primary care dream team can bring together wellness, prevention, and health care to address the whole person,” TPCC’s brief states.

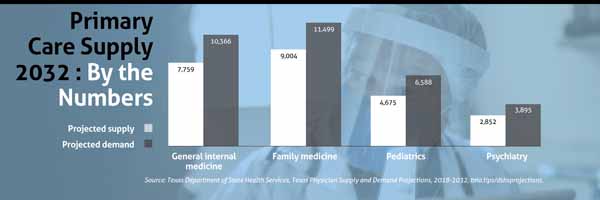

The consortium also noted Texas ranks 47th in the nation in primary-care-physician-to-population ratio, with shortages of primary care physicians in both rural and major metropolitan areas. But it pointed out that telemedicine has emerged during the pandemic as a promising tool for increasing access, recommending the state make permanent the payment parity for telemedicine that Gov. Greg Abbott mandated during the pandemic.

Another avenue for expanding access to primary care: expanding Medicaid, the TPCC and TAFP strategies advocate.

With Texas leading the nation in the number of uninsured residents, TPCC said under the Affordable Care Act, “Texas can design a model best suited to it.” The consortium also raised a community accountable care organization (ACO) model as a method to expand primary care. In a community-based ACO model, safety-net practitioners work under a community-based board that oversees value-based approaches to care.

The TAFP Marshall Plan’s “market-based approaches to decreasing the uninsured” also include a Texas-tailored solution to Medicaid expansion and implementation of community ACO models. (See “The Power of Community,” page 38.)

Among other TAFP suggestions: Lawmakers should foster contracting for direct primary care, in which physicians and patients bypass insurance by having patients pay annual, monthly, or quarterly fees that cover most or all of their primary care.

Specialists remain integral

Advocates for boosting primary care also stress that specialists are still an invaluable part of the health care equation.

“When we start talking about, we need more money for this or that, then the perception historically is that it’s a zero-sum game, and if there’s more money for primary care, there’ll be less money for others,” Dr. Bornstein said. “I don’t really think that’s true. I think it’s a matter of distribution.”

As an example, she cites primary care practices with capitation-payment arrangements in which the practice maintains a relationship with cardiologists or cardiology groups.

“The good thing about that is, if I have a patient that I have a question about, I can call that cardiologist. … Now they may want to see that person, but they don’t necessarily have to. But they are getting paid something for their time, which really at the end, that’s all we have, is our time,” Dr. Bornstein said. “So it’s a different way of engaging specialists. And I can tell you specialists are happy about that, too. Because they don’t want to have a person with complex medical issues that is not well-taken care of, and not well-maintained, present to their office with a problem.”

Louis J. Wilson, MD, president of the Texas Society for Gastroenterology and Endoscopy, is one physician-leader specialist who agrees that primary care is underfunded. He says primary care physicians are key to preventing unnecessary hospitalizations and emergency department visits. But because they’re generally not part of hospital operations anymore, he says specialists are vital for coordinating transitional care for complex hospital patients.

“All health care is local; I firmly believe that. Specialists and primary care providers have to work locally together, and the state cannot replace that,” he said. “When I talk about things like early access to specialists, care coordination through primary care, transitional care for hospitalized patients – all of that stuff is driven by local relationships.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(12):14-20

December 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page