On Nov. 29, 2016, Landon Powell, 22, was released after a two-week stint in the Bexar County Adult Detention Center for marijuana possession. Within 24 hours, he hanged himself. Though resuscitated at the scene, he never regained brain function. He died on Dec. 4.

Known mental illness played a role, as with about 46 percent of all suicide deaths. Five years before, Landon Powell had been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder.

“It was kind of a perfect storm,” said his father Dan Powell, MD, a family physician in San Antonio. “There were a lot of things going on in his life, and none of them were good.”

As with all instances of suicide, the survivors — Dr. Powell, his wife, and daughter — are left with shock, grief, and questions that don’t go away. Those questions especially torment a father/physician who’s been practicing for more than two decades.

“You look back at different moments, and you have a 13-year-old screaming, crying ‘I think I’m going crazy!’ Well, you’re 13 and you’re just hitting your hormones,” Dr. Powell said. “Now, we look at that conversation a little differently. I would have loved to have gone back and asked more questions.”

Dr. Powell has shared his son’s story widely in hopes of raising greater awareness about suicide, a growing public health problem in the United States. One statistic in particular haunts every physician’s exam room: A 2002 American Journal of Psychiatry study found that on average, 45 percent of people who die by suicide have contact with a primary care provider in the month before.

“That’s one of the most important things [many physicians] don’t understand,” according to Jenna Heise, the statewide suicide prevention coordinator at the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC). “Half of people are going to their doctors in the month before their deaths … so there’s a real opportunity there for the docs to reach them.”

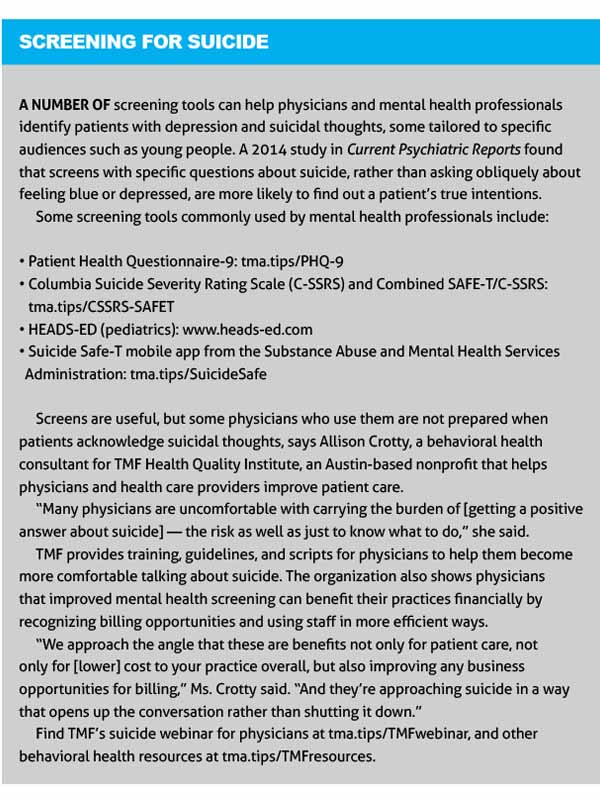

Screening tools are available to help physicians identify people thinking of suicide, and those tools can be helpful if used correctly, says Stacey Freedenthal, PhD, a licensed psychotherapist who specializes in suicide risk and mental health assessment, and who has written about her own brush with suicide as a graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin (tma.tips/NYTSuicideTherapistsSecret).

However, the social stigma around suicide still keeps many physicians and health care workers, as well as patients and their family members, from addressing the topic head on. (See “Screening for Suicide,” page 21.)

“Physicians need to recognize that they’re the frontline person that people go to most often, and they’re in a position to be most effective,” said Dr. Freedenthal, author of Helping the Suicidal Person: Tips and Techniques for Professionals. “Not only can many people not go to a mental health specialist because of finances or whatever, there are many who choose not to because of the stigma.”

Primary care physicians also can help remove that stigma by encouraging conversations about depression and suicide with their patients, says Leslie Secrest, MD, a professor of psychiatry at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Task Force on Behavioral Health.

“[Primary care physicians] may not have all the answers,” Dr. Secrest said. “But [their offices] are a venue in which answers can be found.”

Why more suicides?

The recent deaths of celebrities like chef Anthony Bourdain and fashion designer Kate Spade kept suicide in the news this year. They highlighted statistics the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released in June showing that between 1999 and 2016, suicide rates rose nearly 30 percent nationwide. (See “Suicide Statistics,” page 19.)

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death nationwide, and one of just three leading causes on the rise, along with drug overdoses and Alzheimer’s disease.

In Texas, the rate of suicide is not as high, but it is still serious. In 2015, it was the 12th leading cause of death statewide, and Texas had the 41st highest suicide rate among the 50 states, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS). However, among certain age groups, suicide rates are quite high. Suicide was the second leading cause of death for 15- to 34-year-old Texans after accidents, which mirrors CDC national statistics.

It’s not clear why U.S. suicide rates continue to climb, especially when they are going down in similarly wealthy countries in Europe, Dr. Freedenthal says. There are several theories, including the slow recovery from the Great Recession, stagnant middle-class incomes, and access to firearms. However, there’s no definitive explanation, she says.

“It’s disheartening because there’s been a lot more suicide prevention efforts [in recent years], so we’d expect to see suicides going down,” she said.

There is no typical profile for suicide, Dr. Freedenthal says. There are high-risk groups, like combat veterans, LGBTQ teenagers, people with chronic health issues, and elderly people who have lost a spouse. White, middle-age men account for 70 percent of deaths from suicide each year.

Suicidal thoughts most often stem from clinical depression, Dr. Freedenthal says. However, not everybody who has suicidal thoughts is depressed, and not everyone who is depressed contemplates suicide. It is more helpful to think of suicidal thoughts as a symptom of mental illness, stress, or trauma.

“Nobody’s immune,” she said. “You could have a woman who has no mental illness and hasn’t been through trauma or combat who is suicidal.”

Standing in the gap

Both the U.S. and Texas face a long-standing shortage of psychiatrists. (See “Is Psychiatry Cool Again?” page 40.) But even if there were plenty of psychiatrists, other primary care specialties — like family medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology — are usually in a better position to identify and help the patients who are at risk, says M. Brett Cooper, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and a member of TMA’s Committee on Child and Adolescent Health.

However, not all primary care physicians are comfortable managing medications for mental health conditions, Dr. Cooper says. In his experience, some physicians reflexively refer any case of depression or suicidal intent to psychiatrists, and the shortage of mental health professionals can slow down or stop treatment.

“Our child psychiatrists … really appreciated us being a buffer [for treating depression and related issues] because they really need to deal with the patients who were refractory,” Dr. Cooper said. “If I tried using Prozac — or I switched to one of its effective cousins — and I’m not getting an effective treatment, that’s really where the psychiatrist should come in.”

Serving as a buffer for behavioral health care is important, and primary care physicians should have at least some basic mental health care training. But they also should not feel pressured to forego the expertise of a psychiatrist, said James Halgrimson, DO, an Austin psychiatrist on TMA’s Task Force on Behavioral Health. He points out that the wrong medication can make complex psychiatric conditions like bipolar disorder worse — and can even increase the risk for impulsive suicidal behavior.

“Some of those medications can be very dangerous for them to take if they’re not diagnosed appropriately,” he said.

Even so, Dr. Secrest, also a psychiatrist, says primary care physicians should not be afraid to step up and help fill the void left by the shortage in psychiatry.

“What I want to say to [primary care physicians] is start the medication, then set up a process where it’s monitored by the patient’s family and the physician to see what the response is,” he said. “That’s what I think is the important part — not to make me [as a primary care physician] more hesitant, but make me more observant.”

Team-based approach

Also to fill the void, many medical centers are moving toward integrated behavioral health, a more team-based approach to mental health issues, says Celia Neavel, MD, director of the Center for Adolescent Health at People’s Community Clinic in Austin and an expert in this approach. Integrated behavioral health involves mental health specialists such as psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and other therapists working in teams with primary care physicians to address mental health needs.

“In our clinic, this means that we can have behavior health specialists on the floor with us or whom we can call during clinic hours to help us when a depression or suicide screen is positive,” said Dr. Neavel, a family physician. “Ideally, a social worker can be there while the provider is actually seeing the patient. They can help with screening, resources, follow-up, in-house behavioral health appointments, or even care coordination for a patient needing an emergency referral.”

At the same time, consulting psychiatrists support primary care physicians and providers in diagnosis and medication management for depression and anxiety.

“All our charts are integrated so that we can learn from each other,” Dr. Neavel said.

While this approach is still fairly rare in practice, she says, it offers many benefits: It keeps patients in their medical homes, increases physician comfort with mental illness, reduces stigma, and gives the physician discretion to decide when a mental health specialist is needed.

“It’s still the primary care provider’s patient,” Dr. Neavel said.

Of course, most physicians in Texas don’t have the easy access to the psychiatrists needed to try such an in-clinic, team-based approach. However, they still can reach out to the community to create their own team, Dr. Neavel says, such as mental health specialists, nonprofits, school counselors, and similar professionals who can work collaboratively.

The chronic shortage of psychiatrists creates many challenges. Patients in urban areas often must wait weeks or months to see one. The problem is even more pronounced in rural areas. In Texas, 171 counties (out of 254) have no psychiatrist, according to 2017 DSHS data. (See “Texas Counties Without a Psychiatrist,” page 42.)

Before moving to San Antonio, Dr. Powell, the father whose son died, practiced primary care in Pampa, a small town about an hour’s drive northeast of Amarillo. He had to handle his patients’ mental health and suicidal conditions on his own because there was no other place for them to turn.

“With the small-town docs, it’s their willingness to go there — their willingness to stretch and be a little uncomfortable with medications they don’t have a lot of experience with,” he said. “They just have to make it a priority and do that extra studying to be comfortable with those medications if you haven’t been trained to use them.”

However, he understands the reluctance of primary care physicians to address suicide more directly. First, there is a time crunch of trying to work mental health screenings into a patient visit that may be packed with physical problems. Also, treating psychiatric issues is different from the way they normally practice medicine.

“It’s different, for instance, from diabetes or hypertension, where you have these outcomes where you can measure along the way and say, ‘How are you doing?’” Dr. Powell said. “There’s not any subset of tests you can do in mental health that help in that regard, so I think it’s difficult for doctors in primary care to be as proactive because they can’t measure themselves.”

Becoming the front line

Dr. Powell says his small-town practice made him comfortable with screening for mental illness and suicide ideation. But since his son’s death, he’s made a subtle but important change in the way he asks questions. Typical questions on depression screens are: Do you feel down or blue? Are you feeling hopeless?

“Another way to ask that is, what does someone have to keep them going?” Dr. Powell said. “What do they have to get up out of bed in the morning for? What gives them meaning or purpose? And I think in my practice and certainly in my life, that’s what I’ve focused more on — do my patients have no hope? … That relates to my son’s case. He was running out of purpose, reason.”

Physicians in many states are becoming more involved in suicide prevention, but training is erratic. Most states, like Texas, do not require suicide prevention training for medical professionals. In 2017, Washington became the first state to mandate suicide assessment, treatment, and management continuing medical education for physicians and all health care providers, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

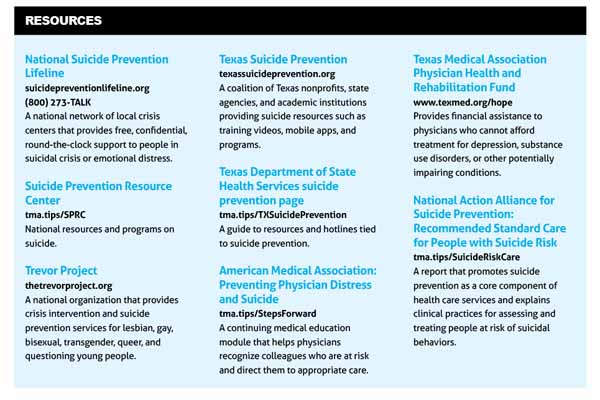

Texas offers physicians some state and local resources. For instance, HHSC contracts with local community mental health centers. On top of psychiatric services, the centers provide a round-the-clock crisis helpline that local physicians can refer patients to in emergencies, like a suicide attempt. (See “Resources,” page 20.)

However, geography can make accessing some of these centers difficult for patients in rural areas. Counties containing large cities like Austin or Dallas have one mental health center, but some centers in West Texas and the Panhandle serve more than 20 far-flung counties.

Thanks in part to TMA advocacy, the Texas Legislature in 2017 enacted a series of reforms designed to improve mental health care in Texas. (See “Thinking Big,” August 2017 Texas Medicine, pages 31-33, www.texmed.org/ThinkBig.) These include Medicaid payment for post-partum depression screenings and annual adolescent mental health screenings.

The legislature also expanded access to telemedicine, allowing physicians to care for patients outside of the traditional office visit. (See www.texmed.org/TelemedicineLaw.) Telemedicine is expected to make delivery of some types of health care — particularly mental health care — easier in remote areas of the state.

“Branching out with telemedicine in the immediate future would be a faster, easier, cheaper option [to address the shortage of psychiatrists],” Dr. Halgrimson said. “But long term, we just need to find more psychiatrists who can actually work interpersonally with the physicians there and in person with the actual patient.”

In the meantime, physician attitudes need to change, Dr. Powell says. To identify and help people contemplating suicide, doctors have to rely more on their bedside manner than test outcomes. Dr. Powell has vowed to be as transparent as possible about his son’s suicide and to use it to help others avoid tragedy.

“I still keep family photos in the exam room,” he said. “They’re a good lead-in for being able to talk about mental health and how it’s affected our family and how we lost our son. I think that opens up communication, number one. And if they’re comfortable talking to you, they’re going to be more likely to talk to you. I think for me that’s something that’s opened some doors.”

Physicians Not Immune

In the United States, about 300 to 400 physicians die each year by suicide, according to a 2018 Medscape report (tma.tips/MedscapePhysicianSuicide).

Because sympathetic colleagues probably underreport physician suicides in death records, this is widely considered a conservative count. Between 2000 and 2014, suicide was the second leading cause of death among medical residents, after neoplastic disease, according to a 2017 study in the journal Academic Medicine.

As with other patients, most physician suicides are caused by untreated or poorly treated depression, according to Medscape. Physicians often don’t seek treatment because they fear being damaged professionally. A 2011 survey published in The Archives of Surgery found that about 60 percent of surgeons who had suicidal thoughts were reluctant to get help because they feared it could affect their medical license.

The Texas Medical Association has advocated strongly over the years to change physician license applications and credentialing documents to do away with requirements for overly broad disclosure of physicians’ mental health history.

TMA also offers continuing medical education designed to help physicians better understand suicide and improve both patient and physician well-being (www.texmed.org/PhysicianSuicide).

TMA’s Physician Health and Rehabilitation Fund (www.texmed.org/hope) also provides financial assistance to physicians who cannot afford treatment for depression, substance use disorders, or other potentially impairing conditions.

Suicide Statistics

In 2016, nearly 45,000 suicides occurred in the United States among people 10 and older, a rate of 15.6 suicides per 100,000 people.

Texas had 3,368 suicides in 2015; its rate was 12.4 per 100,000.

From 1999 to 2015, suicide rates increased among both sexes, all racial and ethnic groups, and all age groups under 75. Adults 45-64 had the largest overall increase.

In 2016, suicide was the second leading cause of death among people 10 to 34, after unintentional injury.

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual young people are five times as likely to have attempted suicide as heterosexual young people. Forty percent of transgender adults report having made a suicide attempt.

In 2014, an average of 20 military veterans died by suicide each day.

From 2000 to 2016, 52 percent of suicides were caused by firearms, the most common method, followed by suffocation (24 percent) and poisoning (17 percent).

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Texas Department of State Health Services; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; Suicide Prevention Resource Center; National Center for Transgender Equality

Tex Med. 2018;114(11):16-21

November 2018 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page