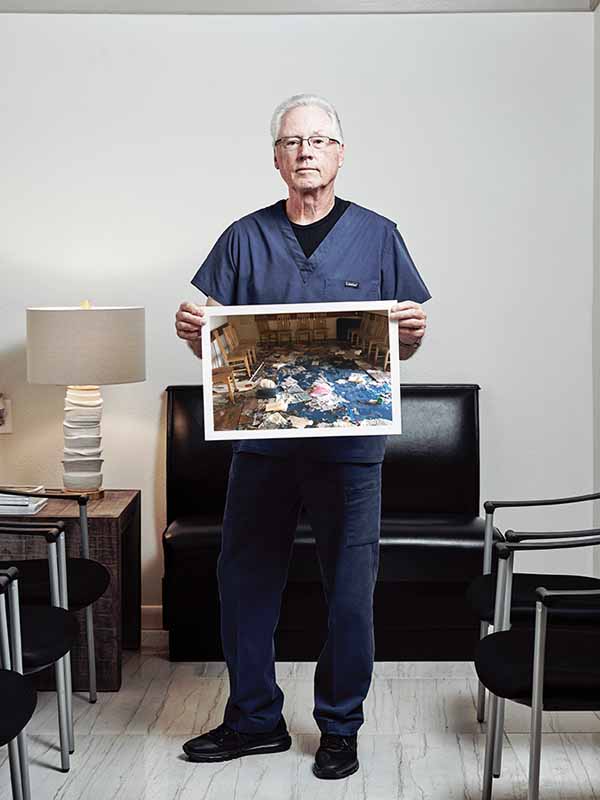

Hurricane Harvey was not kind to family physician Jim LaRose, DO. His Bretshire Medical Clinic in northeast Houston took on about three feet of water during the storm. But that was just the start of Dr. LaRose’s problems.

“On top of the flooding, there was quite a bit of looting, which also took place in our office,” he said. “There was also a pharmacy attached to [the office], and they cleaned out the pharmacy, too.”

Dr. LaRose has been in practice for more than four decades and he had rebuilt after previous hurricanes. But the damage Harvey caused was so extensive he didn’t know if he had the heart to do it again.

“I cried,” he said. “This time, I was about to close up shop. There was a guy who came by, I don’t even know if he was a patient. He was just walking by the clinic. I introduced myself and he introduced himself, and he said, ‘Look, we just don’t have any good doctors in this area. I hope you’re not planning on closing up.’ And I said, ‘I’m pretty much almost there.’”

Dr. LaRose’s clinic serves mostly low-income, African-American, and Latino resi-dents. Those are the groups hardest hit by Harvey, according to a December 2017 survey of 24 affected Gulf Coast counties conducted by the Episcopal Health Foundation (EHF) and the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. (See “Harvey Recovery: By the Numbers", page 21.)

The survey initially found that blacks were most likely to report health problems due to Harvey. These could include physical ailments, like worsening asthma and allergies, as well as mental health issues, like increased depression or anxiety. The survey also found 53 percent of Hispanics and 39 percent of blacks were more likely to lack access to both health insurance and physicians, as well as other health care providers. Kaiser and EHF are expected to release the latest results of their survey in August.

Studies of the public health, mental health, and environmental effects of the storm are still under way, and could take years to complete. Meanwhile, research done in the six months post-Harvey shows a long road to recovery in these areas.

The full impact of Harvey won’t be known anytime soon simply because there aren’t enough resources dedicated to evaluating it, says Umair Shah, MD, executive director at Harris County Public Health. Likewise, there weren’t enough resources for the im-mediate aftermath and the ongoing recovery.

“Given the enormity of Hurricane Harvey, we didn’t have enough epidemiologists, we didn’t have enough environmental sanitarians, and we didn’t have enough nurses and clinicians,” Dr. Shah said. “So while we were able to reach out to partners and get some of that filled in by volunteers and other community members, I think it still speaks to the fact that public health still needs to be invested in.”

George Santos, MD, a psychiatrist and president of the Harris County Medical Society, says the data that is available reflects Texas’ ongoing status as the state with the highest rate of uninsured people at 16.6 percent. The health problems that creates become more severe when a disaster like Hurricane Harvey strikes.

“[Lack of health insurance coverage] is an infrastructure problem we can solve, but for a variety of reasons we don’t,” he said. “That’s in the best of circumstances, and then you have a natural disaster on top of it.”

Public health impacts

Access to care was better during Harvey than during past storms, according to Dr. Shah. He says only about 10 percent of the Houston area’s 20-plus hospitals shut down or cut power temporarily because of the storm (and one closed permanently). After previous storms, medical facilities made important infrastructure improvements — like installing “submarine” doors — to keep out flood waters.

Also, emergency shelters and clinics popped up all over the area in Harvey’s aftermath.

Dr. Santos says physicians and other health workers at those shelters responded much more nimbly to patient needs, thanks to important lessons learned from previous storms. For instance, mental health workers actively patrolled shelters looking for people with mental health issues rather than waiting for them to ask for help.

“It was a really shining example of the commitment of medical professionals,” he said. “There was just a dramatic and ready response — people giving huge amounts of time to operate these clinics.”

Immediately after the storm, there was an uptick in gastrointestinal illnesses, respiratory illnesses, and skin infections, Dr. Shah says. All of these have since returned to pre-storm levels. Meanwhile, aerial spraying for mosquitos kept vector-borne illnesses largely in check. However, exposure to mold remains a serious problem because many people have not had the money to fix flood-damaged homes, he says.

The long-term environmental effects on people’s homes and health is also an area ripe for study.

Data collected so far by the U.S. Coast Guard National Response Center show there were 90 incidents reported in the Houston-Galveston region during Harvey involving the release of more than 700,000 gallons of pollutants into the water or on land. Because these are just reported incidents, they probably reflect only a fraction of the actual amount of pollution, according to the Houston Advanced Research Center.

Many area residents reported smelling air pollution or seeing water pollution that has yet to be investigated, in part because of limited state and local resources, says Kelly Haragan, a clinical professor and director of the Environmental Clinic at The University of Texas at Austin School of Law. She cites one example in Port Arthur.

“[Residents there] know things were spilled on their properties,” she said. “They saw it. It was in the flood waters, it was in their homes. And then the flood waters have receded, but there hasn’t been any testing on individual properties to see if there are contaminants in the soil.”

Dr. Santos points out an equally important problem: Many people cannot return home at all.

“I still have a lot of patients who are still living in temporary housing because of the complexity of damage they had, dealing with contractors, dealing with FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency), dealing with insurance — those kinds of issues,” he said. “Those kinds of delayed issues compound the trauma of the hurricane.”

Mental health challenges

In fact, the mental health impacts of the storm have proved particularly challenging to address.

The EHF-Kaiser December survey found that 13 percent of people in the Gulf region believed the trauma of the storm affected their mental health. For those in the Beaumont-Port Arthur area, that number was 33 percent. However, the full picture of Harvey’s impact on mental health won’t be known for months or years, says Elena Marks, EHF president and chief executive officer.

“One of the things we’ve learned from working with people in other disasters is that the mental health impacts generally take six to 18 months to fully show up,” she said. “People sort of hold it together for a while [after the storm] — and then they don’t.”

The situation is compounded by the fact that many medical facilities are slowly coming back. For instance, the northeast clinic for the Harris Center for Mental Health and Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities was effectively shut down until this summer. It is a major part of Harris County’s public program for mental health.

Another ongoing health survey by The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston found in December that 55 percent of people in Harris County felt life had gotten back to normal. However, that number dropped to 40 percent among those who suffered serious damage to a home or vehicle. UT Houston expects to have new data in September.

Adults are most vulnerable to mental health problems because they have the most responsibilities and the most worries, says Andy Keller, PhD, president and CEO of the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute (MMHPI) in Dallas. After traumas like Harvey, rates of post-traumatic stress rise by six times among adults and triple among children.

However, that still means a 300 percent increase for children — and the impact will be felt statewide.

“This affects everything — even in the Panhandle or El Paso,” Dr. Keller said. “You have students today who are relocated there from the storm-affected area, who are now living in a different place than where they grew up, and that affects that school, it affects those students. We saw that after Hurricane Ike [in 2008].” (See MMHPI resources on mental health for children at tma.tips/MMHPI.)

Physicians across the state should routinely screen patients young and old for depression and anxiety, Dr. Keller says. Many physicians are understandably reluctant to do this because the state’s chronic lack of psychiatrists leaves them with nowhere to refer patients. While psychiatrists are needed for more serious mental health issues like bipolar disorder, research has shown that basic treatment of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress by primary care physicians, while not optimal, can be effective and should be done, he says.

“We screen every child for diabetes and we don’t wring our hands about whether or not we’ll be able to treat them all,” Dr. Keller said. “You go to a pediatrician and he says, ‘I don’t want to screen them all [for mental health issues] because who am I going to refer them to?’ You don’t [always] need to refer them. And even if you can’t refer them, wouldn’t you rather know?”

Meanwhile, private physicians like Dr. LaRose also are finding it hard to get back on their feet fully so they can be there for their patients. (See “The Way Back,”) With assistance from the Texas Medical Association Disaster Relief Fund, he was able to get his practice running again in a temporary building about 2 1/2 weeks after the storm blew in. But Dr. LaRose says hassles with contractors, the U.S. Small Business Administration, and insurance companies slowed the rebuilding of his flooded office.

Enthusiastic people from the neighborhood and elected officials attended his clinic’s grand reopening ceremony in April. Even so, Dr. LaRose says he’s worried about the clinic’s future. He’s 75 years old, so if another big hurricane floods the new office, he doesn’t anticipate rebuilding. He says the neighborhood only has two doctors left — him and one other general practitioner who’s in his 80s.

“We’re trying to find somebody who will work with the people in this area and keep [the practice going],” Dr. LaRose said. “Basically, for the people in the area, when me and the other doctor close the door, there’s nothing left.”

13%

Had a household member with a new or worsening health condition

26%

Had problems paying medical bills

31%

Did not fill a prescription, cut pills in half, or skipped medicine for a new or worsening health condition

31%

Had no usual place to go for health care, or their usual source of care was the eme-gency room. Rates were higher among blacks (39 percent), Hispanics (38 percent), and those with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line (40 percent).

36%

Put off medical care for a new or worsening health condition

Source: Episcopal Health Foundation and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation December 2017 survey of a 24-county area affected by Hurricane Harvey, tma.tips/EHFHarveySurvey

Hurricane Harvey Registry

Harris County Public Health has partnered with Rice University in Houston and other local and national organizations to create the Hurricane Harvey Registry. It will collect health information from people who lived through the storm, and the data will shape planning for future disasters. Visit

harveyregistry.rice.edu.

Tex Med. 2018;114(8):18-29

August 2018 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page