After completing his residency training at Columbia University and obtaining a J-1 visa waiver, Jayesh “Jay” Shah, MD, moved to Uvalde to help address its medical care shortages. For four years, the now-president of the Texas Medical Association practiced in the rural community – and became patients’ lifeline in an area where physicians are often scarce.

Dr. Shah acknowledges his story is far from unique. As international medical graduates (IMGs) increasingly enter the U.S. physician workforce, a growing number are providing care in rural areas, according to an Aug. 14 research letter in JAMA.

That may be because upon completion of training in the U.S., IMGs who hold a J-1 visa for educational exchange and decide they want to remain in the U.S. to practice must return to their home country for a period of two years before applying for immigration to the U.S., according to the U.S. Department of State. An exception to the rule is to receive a waiver of the two-year waiting period that requires the physicians to practice in a medically underserved area in the U.S. for three years.

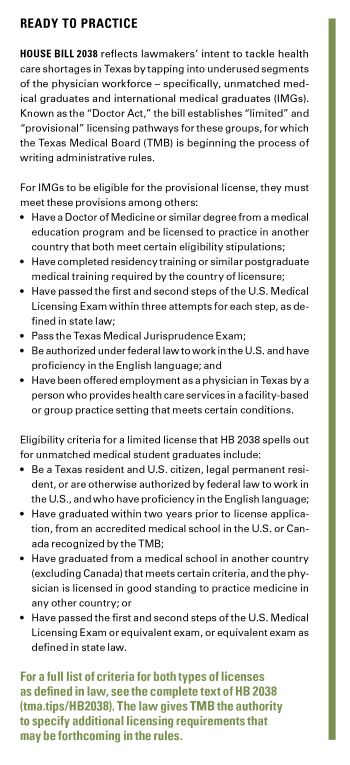

As physician shortages grow worse, political leaders across the country are looking to IMG physicians who have not been eligible for licensure due to lack of postgraduate training in the U.S. The Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) found that as of August 2025, 18 states have enacted legislation that allows internationally educated physicians to gain some form of licensure without accredited postgraduate training in the U.S.

Meanwhile, 12 states have created a new category of license for unmatched medical school graduates, per FSMB. Texas followed suit during the 2025 legislative session with a law that creates new licensure pathways for IMGs and unmatched medical school graduates.

Rep. Tom Oliverson, MD (R-Cypress), who authored House Bill 2038, the so-called “Doctor Act,” with Rep. Suleman Lalani, MD (D-Sugar Land), and others, is optimistic that thinking creatively can alleviate Texas’ health care shortages in underserved areas and halt scope-of-practice creep in the process.

“Both sets of physicians have infinitely more training and experience than your average [nonphysician] practitioner,” Representative Oliverson told Texas Medicine. “This law allows them the same authority that a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, in many instances, already have.”

But as HB 2038 bypasses traditional requirements to allow certain medical graduates to practice medicine in the state, it may raise more questions than answers.

For instance, to renew their provisional licenses, HB 2038 requires IMGs to practice in rural and medically underserved areas as designated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – but there is no such requirement for the first two years, meaning IMGs who practice under the initial license do not have these restrictions. However, a requirement of the initial license is to practice in a facility-based group practice setting with an accredited residency program.

Meanwhile, Texas’ number of unmatched medical school graduates was as low as 12 in 2024, per TMA’s annual surveys of Texas medical schools. This has raised concerns that even with a limited license, unmatched physicians may not have a significant impact on alleviating Texas’ care shortages.

“Having physicians like me practice in rural and medically underserved areas … is part of a solution to address a lack of care in Texas,” said Dr. Shah, a San Antonio internist and wound care specialist. However, “without rulemaking, we don’t know yet what will happen.”

Although HB 2038 took effect Sept. 1, it requires the Texas Medical Board (TMB) to develop administrative rules no later than Jan. 1, 2026. As of this writing, TMA was in communication with TMB on its rulemaking process with plans to weigh in. In e-mail correspondence with Texas Medicine, the board said stakeholder feedback from a meeting in September “will shape the proposed rules for publication in the Texas Register and public comment” that follows the release of such proposed rules. (TMB proposed rules on Nov. 7 post-publication of this story. Those rules are not final and are subject to change. TMA will submit comments on the proposed rules and will provide an update after the TMB adopts its final rule.)

International complexities

Internationally educated physicians comprise 25% of the U.S. physician workforce and make up 50% of active physicians in geriatric medicine and nephrology and 30% of active physicians in infectious disease, internal medicine, and endocrinology, per the American Medical Association.

As part of that path, however, IMGs experience unique barriers to practicing in the U.S., says Vivek Rao, MD, such as federal immigration hurdles and additional postgraduate medical training, for which they historically experience lower match rates. A member of TMA’s Council on Legislation and the son of a physician who immigrated to the U.S., Dr. Rao took special interest in HB 2038 and was involved in legislative discussions surrounding the bill.

HB 2038 attempts to capture some of that workforce by directing TMB to issue a provisional, two-year medical license to IMGs who meet defined criteria. These provisional licenses are renewable once if the licensee progresses toward some aspects of standard licensure through additional examination and other criteria.

The law, however, does not include longstanding Texas licensing criteria mandating IMGs to complete at least two years of graduate medical training at an American or Canadian program approved by TMB, a requirement that often forced non-U.S. medical graduates who have already completed training in their countries of origin to do so again, Dr. Rao says.

Although Dr. Rao has concerns about HB 2038’s implementation – he supports the idea of improving access in rural areas by alleviating IMGs’ barriers to practice “so long as these physicians are properly vetted” – he’s hopeful it will provide IMGs with the freedom to provide care, while freeing up Texas residency slots.

“HB 2038 can be seen as a win-win for some,” said Dr. Rao said. He added: “There were a number of bills introduced this session that aimed to address rural health care access by removing physicians from the health care team, and this is one of the few bills that does not do that.”

Similar programs in other states differ on how an IMG can hold licensure. As of August 2025, 17 other states have enacted legislation allowing a certain type of licensure for IMGs without post-graduate training in the U.S. or Canada. These states’ laws vary in their initial requirements for licensure, term of licensure, and required practice settings – creating a patchwork of programs IMGs must wade through.

In 2025, the national Advisory Commission on Additional Licensing Models, created in part to address a lack of standardized processes for IMG licensure in new laws across the country, sought to address concerns in its initial guidance to states. Designed to guide and advise state medical boards, state legislators, policymakers and others, and inform their development and/or implementation of laws specific to the licensing of physicians who have already trained and practiced medicine outside the United States or Canada, the group released key recommendations and a toolkit in separate advisories.

However, the commission’s recommendations are not a “catch-all cure” for alternative pathways, especially as their adoption could vary by state, warned Dallas obstetrician-gynecologist Yolanda Lawson, MD, a member of the commission and TMA’s Council on Socioeconomics.

Meanwhile, Texas’ bill “has its own issues, namely a lack of clarity,” she said.

For now, the law does not impose a requirement for IMGs to practice for any length of time outside of the U.S. before entering the country, nor does it set limitations on the type of patient care IMGs can provide.

Nor does HB 2038 mention the delegation of prescriptive authority for this type of provisional medical license, or how IMGs with this license can expect to receive payment. Medicare typically does not pay IMGs for the care they provide, unless they are fully licensed, enrolled in the program, and meet all federal and state regulations.

A Medicare intermediary for Texas confirmed with TMA staff that physician graduates are not recognized as health professionals by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, meaning the agency will not pay for their services.

Similar concerns exist for how HB 2038 could also maximize use of unmatched physician graduates, another untapped portion of the physician workforce.

Texas isn’t alone in grappling with how to deploy unmatched medical graduates for medical practice, Representative Oliverson said, calling HB 2038 a recognition that their careers and potential “should not be wasted.”

Twelve states have implemented “assistant physician” or similar programs in recent years. Each allows unmatched graduates to practice under physician supervision, some with limited uptake and mixed outcomes. As of 2022, Missouri’s assistant physician program launched eight years prior, for example, has offered only 348 active licenses, and it is not known how many are currently practicing.

HB 2038 similarly allows TMB to issue a limited medical license to qualified applicants who are medical school graduates not enrolled in a residency program, referred to as “physician graduates.”

Under the new legislation, physician graduates’ practice is limited to the supervision and delegation of a sponsoring physician with an unrestricted medical license in Texas, under a supervising practice agreement in a county with a population below 100,000. In Texas, 213 counties have populations below 100,000, according to TMA’s 2025 workforce report.

The physician graduate’s practice is limited to the medical specialty of the supervising physician’s board certification.

Each year, thousands of newly minted U.S. medical school graduates find themselves without residency placement at the end of the annual Match Week, an essential step to full medical licensure. This year, the National Resident Matching Program reported over 1,900 unmatched MD and DO graduates. Many graduates go on to match soon after, but that data is not officially reported. Having any U.S. graduates go unmatched is of concern when the country is projected to face a shortage of up to 124,000 physicians by 2034, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

“We are not training enough physicians to meet current or future demand.” Representative Oliverson said. “We need to think outside the box for ways to get more qualified people practicing medicine so that we don’t have these huge health care shortages.”

Representative Oliverson said that traditional requirements have left many “without direction, in limbo.” Although unmatched medical graduates may reapply for residency in subsequent years, the longer they are without a residency position, it is likely the less competitive their applications become.

“I have met [unmatched graduates] who have medical knowledge and experience, but cannot treat patients until they start over again,” he said. “They’re in this no man’s land where they have infinitely more training and experience than your average practitioner but still have to delay their entire careers.”

Despite its promise, physicians like Stephen Whitney, MD, immediate past chair of TMA’s Committee on Physician Distribution and Health Care Access, caution against significant gaps in HB 2038 including a lack of a limit on the number of years an unmatched medical school graduate can work under the new title of physician graduate and no clear pathway to specialty-board certification.

“Are physician graduates going to be paid in full, or will there be a lesser payment for this type of a physician? Will supervisors be required to pay these graduates out of their own pockets? How do we ensure their treatment is fair and equitable? There are just so many questions,” said Dr. Whitney, a pediatrician in Missouri City. “It’s welcome that we’re providing unmatched graduates with a way to serve rural communities, but we must ensure the license does not become a stopgap that delays essential training.”

He has long recommended unmatched medical school graduates to take a year to regroup, strengthen their applications, improve test scores, and reapply the following year.

TMA supports state grant programs that develop and fund one-year transitional year residency positions to specifically assist unmatched Texas medical students to find a match in Texas. A state budget rider introduced during the 2025 Texas legislative session aimed to create and secure funding for such a program but was left on the table after final negotiations.

Dr. Lawson has other concerns: medical liability and physician graduates leaving rural areas after their two-year provisional period. HB 2038 mandates that a sponsoring physician who enters into a supervising practice agreement with a physician graduate retains “legal responsibility for a physician graduate’s patient care activities, including the provision of care and treatment in a health care facility.”

“How can you incentivize a physician to enter into this supervision agreement, when they may take the full brunt of liability?” she told Texas Medicine. “And the bill is framed around rural communities, but there’s nothing there to say that a physician graduate will stay in a particular community.”

TMB is still formulating HB 2038 rulemaking related to physician graduates, including:

- Practices and rules for the supervision of physician graduates, including the number of physician graduates a physician can supervise;

- CME regulations; and

- Any other matter necessary to ensure protection of the public, including disciplinary procedures.

“This [HB 2038] is certainly, in my opinion, not going to be the end to Texas’ health care shortages,” Dr. Lawson said. “We’ll just have to wait and see.”