When the COVID-19 vaccine rollout began in mid-December 2020, many physicians, advocates, and community leaders worried the health disparities laid bare by the pandemic would repeat themselves. But improved data collection and innovative outreach efforts – many of them led by Texas physicians and medical students – have helped close these gaps.

At first, such an outcome seemed unlikely. In May 2021, white Texans were being vaccinated against COVID-19 at a rate 12% higher than Black Texans and 7% higher than Hispanic people, according to an October 2021 article published in the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities.

Ogechika Alozie, MD, an infectious disease specialist and member of the Texas Medical Association’s COVID-19 Task Force, says a history of discrimination in medicine and a health care workforce that does not represent its patient population have eroded trust among Black and Hispanic communities. (See “Diversity in Medicine,” page 26.)

Other factors that contributed to these early gaps include incomplete data collection, an elderly population that skews less diverse than the state population, and inequitable access to COVID-19 vaccine sites, public health experts say.

Such vaccine rate inequities compounded existing pandemic health disparities. A January 2021 report by the Episcopal Health Foundation estimates there would have been 24,000 fewer COVID-19 hospitalizations and 5,000 fewer deaths in Texas through September 2020 if Black and Hispanic populations were hospitalized with the virus and died from it at the same rate as the non-Hispanic white population.

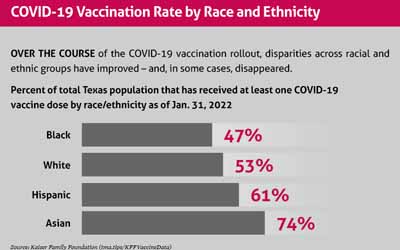

As the vaccine rollout continues, however, Texas has seen COVID-19 vaccination rate disparities across racial and ethnic groups lessen or even disappear. (See “COVID-19 Vaccination Rate by Race and Ethnicity,” below.)

These trajectories largely map onto national trends as well (tma.tips/KFFVaccineData).

Dr. Alozie says physicians and other health care professionals of color help strengthen trust in medical expertise among Black and Hispanic communities, which in turn counteracts vaccine hesitancy. He’s seen this firsthand in El Paso County, where he has lived and practiced for 12 years.

El Paso has historically posted strong vaccination rates. This success continued during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. As of late March, 99.99% of the county population aged 5 and older had received at least one dose, compared with 76.47% statewide, according to Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) data.

“When you have people of color in health care, it’s easier for people in those communities to trust the message,” Dr. Alozie said. “You need to have the right messenger.”

A tailored approach

Racial and ethnic groups can have different motivations for vaccine hesitancy or low vaccination rates says John Carlo, MD, a public health physician in Dallas and a member of TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force.

For instance, research shows the overall Asian population tends to have widespread trust in vaccines and public health guidance, but it is made up of diverse communities that require tailored outreach.

Among white Texans, vaccine hesitancy is likely fueled more by political beliefs and misinformation (tma.tips/February2021VaccinePoll).

Meanwhile, studies show Black and Hispanic communities initially reported higher rates of vaccine hesitancy than the overall population, despite being disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. The reasons for this are myriad and heterogenous but include more limited access to vaccine distribution sites, increased vulnerability to misinformation, concerns that they will miss work due to the possible side effects, and distrust of the medical establishment based on previous and historic experiences.

In such cases, Dr. Carlo says an established relationship with a primary care physician can help dispel misinformation and address hesitancy.

Dr. Alozie adds that it is critical physicians and other health care professionals address patients’ specific fears, without moralizing their decision to get vaccinated.

“One of the flaws and the failures that I saw in the public health messaging, and I was probably guilty of myself, was the absolutism,” he said. “People need to be talked to with honesty and openness and acknowledgement.”

Although Black Texans still lag slightly behind white Texans when it comes to the COVID-19 vaccination rate, research suggests Black Americans are growing less vaccine hesitant at a faster rate than their white counterparts.

“A key factor associated with this pattern seems to be the fact that Black individuals more rapidly came to believe that vaccines were necessary to protect themselves and their communities,” according to a January 2022 JAMA Network Open study (tma.tips/JAMAHesitancyStudy).

Physician-led results

Improved demographic data collection helped DSHS, local public health agencies, health care professionals, and community organizations better target outreach according to the greatest need. Texas physicians and medical school students have played a pivotal role in this process.

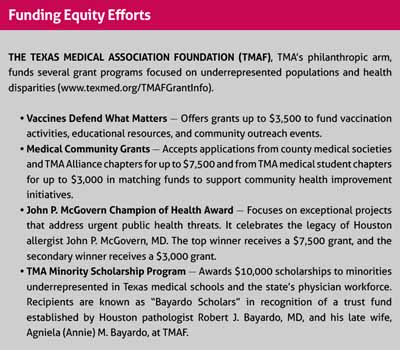

For instance, the North Texas Medical Society Coalition, which represents approximately 12,000 physicians, debuted a nine-part video series, Physicians and Faith, in October 2021, thanks in part to a TMA Foundation-funded Vaccines Defend What Matters grant. (See “Funding Equity Efforts,” below.)

The videos show conversations between nine local faith leaders, mostly from churches with largely Black congregations, and physicians from those communities. The pairs discuss a wide range of common vaccine myths, including those about fertility and childbearing; the inclusion of Black participants in vaccine clinical trials; the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color; and building trust between Black and medical communities.

Dallas internist Beth Kassanoff-Piper, MD, immediate past president of the Dallas County Medical Society and past co-chair of the coalition, says physicians were motivated to develop the series after witnessing the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black and Hispanic communities. They also knew firsthand how effective one-on-one conversations could be in dispelling vaccine hesitancy.

“We knew that we were not able to reach everyone who needed to hear that message,” she said.

Anecdotally, the coalition has received positive feedback about the series. Although hard data have proved elusive, physician members also are seeing the needle move in the right direction.

“The numbers of people getting vaccinated are going up,” Dr. Kassanoff-Piper said. “Not so much in the white community, but certainly in the Black and Hispanic communities.”

Across the state in El Paso, RotaCare, a student-run community clinic founded by the TMA Medical Student Section chapter at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Paul L. Foster School of Medicine, is preparing for its second annual summer series focused on COVID-19 vaccine education.

Last year, the clinic aimed to combat vaccine hesitancy among its patient population, which is largely underserved, uninsured, and living in the country without legal permission. This year, the clinic is looking to widen its reach.

Soroush Omidvarnia, a second-year student at the Foster School of Medicine and student director of RotaCare, says the clinic is learning from last year’s event and building on the success of El Paso County’s vaccination effort.

The clinic’s educational materials were not accessible to everyone who attended last year. So, the chapter is working to make them easier to understand, both in English and in Spanish, regardless of reading level.

The clinic also wants to expand its reach beyond its existing patient population and into other marginalized communities.

“We know that El Paso has done a great job vaccinating people,” Mr. Omidvarnia said. “Our plan this year is actually to expand our net not just to the population where our clinic is located but also to … the homeless communities around our clinic.”

Tex Med. 2022;118(5):41-45

May 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page