At a recent professional conference, Palo Alto ophthalmologist Ann Caroline Fisher, MD, and a colleague led a roundtable discussion titled “Diversity, Equity, and Insanity: Can We Have a Candid Conversation?” She says the discussion revolved around a response to an article describing ophthalmology as one of the least diverse medical specialties. The response disparaged diversity quotas and other efforts to improve representation in medicine, including of people like her, a first-generation American born to a half Peruvian father and a half-Chinese mother.

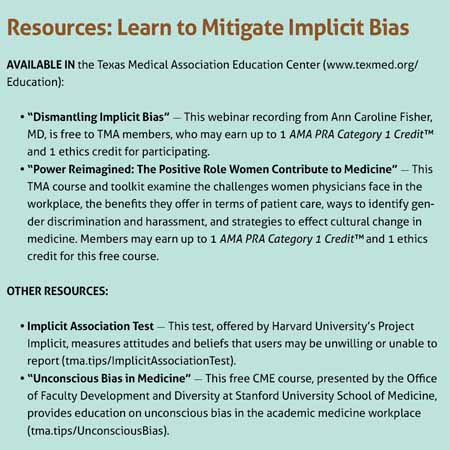

Motivated by this and other experiences, Dr. Fisher now helps others in medicine tackle implicit bias as the director of diversity, equity, and inclusion at the Byers Eye Institute Department of Ophthalmology at Stanford and as a visiting speaker. She presented a webinar, “Dismantling Implicit Bias,” at TexMed, the Texas Medical Association’s annual conference, in 2021. (See “Resources,” page 29.)

Implicit bias is unconscious, hidden-brain-type behavior, Dr. Fisher explains in the webinar. It relies on learned stereotypes that are often automatic, unintentional, and deeply ingrained. In high-stress situations, people often revert to these mental shortcuts, which can influence their behavior and lead to discriminatory actions.

This can have serious implications for health care.

“In medicine, we’re taught to make decisions and make observations from the moment a patient walks in,” Dr. Fisher told Texas Medicine.

Because individuals often take their cues from the top, she says institutions like state medical associations play a critical role in rooting out implicit bias, which is often built into systems and processes.

“The fact that [TMA], with its 56,000-plus members, is making [implicit bias] a part of its teachings and mission says a lot about the organization,” Dr. Fisher said. “Institutional commitment is critical.” (See “Moving People Together,” page 16.)

Addressing implicit bias

Dr. Fisher encourages physicians to acknowledge personal and systemic biases, using tools such as the Implicit Association Test, and to identify their negative consequences. (See “Resources,” below.)

For instance, half of a sample of white medical students and residents endorsed at least one false belief about Black patients, such as that they have thicker skin than white patients or that their blood clots faster, according to a 2016 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Those who endorsed such beliefs rated Black patients’ pain levels as lower than white patients, suggesting they may use those beliefs to inform medical judgments, contributing to racial disparities in pain assessment and treatment.

Similarly, Dr. Fisher cites a 2019 article, “Unconscious Bias: Addressing the Hidden Impact on Surgical Education,” which provides examples of biased comments regarding women, such as: “She’s technically very good. She operates like a man!”

Within the patient-physician relationship, such biases can contribute to negative patient outcomes, health inequities, and an erosion of trust. In the workplace, they can fuel physician pay gaps, decreased productivity, and attrition.

To mitigate implicit bias on an institutional level, Dr. Fisher espouses a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, institutions should look outward, diversifying their talent pool and improving representation among the people they bring into their fold. On the other hand, they should look inward, figuring out how they can retool their systems and train their teams to support a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable workplace.

“Everything is a domino effect,” she said. “You can recruit [underrepresented racial and ethnic groups] to academic institutions, but if they don’t feel they belong … then there’s attrition, so it’s sort of a zero-sum game.”

When it comes to diversifying the talent pool, Dr. Fisher stresses the importance of mentorship. (See “Preparing the Path,” page 33.)

Stanford, for example, offers several programs targeted at high school and historically Black college and university medical school students. By bringing them to campus for a summer lecture program, research rotation, or clinical away rotation, the university fosters exposure and encourages success, she says.

Dr. Fisher also suggests institutions invest in outreach and employ a more holistic approach to reviewing applications, as traditional methods may fail to capture exceptional candidates. For instance, residency programs might consider redacting applicants’ medical school to counteract implicit biases toward elite academic institutions.

“Then you’re saying it doesn’t matter where you went to medical school,” she said. “What really matters is your dedication to the field, your personal statement, your distance traveled, and what you were able to do with the resources you had at [your] institution.”

Interventions could prove fruitful in Texas, where the physician workforce falls short of equitable representation. Women – half of the state population – account for just over a third of the Texas physician workforce, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges 2021 State Physician Workforce Data Report. The share of Texas physicians who are Black is less than half of the share of Texans who are, and the share of Texas physicians who are Latino is less than one third. (See “Diversity in Medicine,” page 26.)

“We treat diverse populations, and our medical community or organizations should reflect that richness and diversity of our community,” she said.

When it comes to institutional housekeeping, Dr. Fisher encourages institutions to be transparent about their processes for mitigating implicit bias, to collect data on whether those processes are effective, and to be accountable if they do not meet their stated goals or if leadership is straggling on the issue.

“The reason … why I mention leadership is because we set the example,” she said. “Trainees learn by watching us.”

TMA policy already incorporates many of Dr. Fisher’s recommendations, for instance by urging Texas medical schools and post-graduate training programs to diversify their applicant pool and to offer support services to students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups; member physicians to mentor their younger colleagues; and state lawmakers to fund medical school positions for qualified students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

Dr. Fisher commends these efforts, which help set the tone for medical institutions across Texas and serve as an example to other states.

Tex Med. 2022;118(5):28-30

May 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page

“This is leadership in action,” she said.