Thanks to physician-led advocacy, government payers are paving the way to better address social determinants of health.

Houston family physician Lindsay Botsford, MD, received a call in late February from a Medicare patient with shingles. She prescribed an antiviral medication to treat the infection – and then the real work began.

The patient had screened positive for several nonmedical risk factors that nevertheless were impacting her care: She lived alone, didn’t have any family or friends to help her, and lacked access to transportation. As a result, she couldn’t easily pick up her prescription. Fortunately, Dr. Botsford’s value-based care practice, Iora Primary Care in Houston, had invested in the staffing and processes necessary to identify and troubleshoot these social determinants of health.

First, staff offered to provide Dr. Botsford’s patient a ride to the pharmacy, but she didn’t feel comfortable driving with a stranger. Then, they found a pharmacy that offered same-day delivery. The 91-cent copayment was within the patient’s limited budget – she had $10 to last the rest of the month – but she didn’t have a credit card, which was the required payment method. Ultimately, the pharmacy, with which the practice had built a relationship, made an exception and allowed the patient to pay with cash, ensuring she could obtain the necessary medication to treat her shingles effectively.

“The time it takes to operationalize the [social determinants of health] screening in a practice is not trivial,” Dr. Botsford said. “It does take quite a bit of work to do it effectively.”

Many in health care refer to this process as “closing the loop,” since it helps connect patients who screen positive for social risk factors to services that resolve them, many of which are outside of the typical clinical workflow.

This work may soon become more feasible. After more than a decade of physician-led advocacy, The Physicians Foundation, with the support of the Texas Medical Association and others in organized medicine, secured a preliminary victory this past December in implementing quality measures that recognize the impact social drivers have on patients’ health, and that ultimately can help compensate physicians for their efforts in addressing these factors.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) added two health-screening measures – as proposed by The Physicians Foundation and endorsed by TMA – to its official list of measures under consideration. CMS is expected to propose the measures for use in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System and the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program as part of its 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposal, due out this summer.

Meanwhile, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) is considering a request that Medicaid starting this fall pay for food insecurity screenings as part of preventive checkups for children, thanks also to advocacy by two Texas physicians, TMA, and the Texas Pediatric Society.

Texas physicians are optimistic that these federal- and state-level policy changes will encourage private payers to follow suit, a situation TMA continues to monitor.

Given the broad impact social determinants of health are known to have across the health care spectrum, “this is one [situation] where all boats rise,” Dr. Botsford said. “The more that [recognition] can become part of primary care everywhere, the better it is for our patients.”

Physician-led measures

Physicians have long been aware of how social determinants impact their patients’ health, fuel disparities, increase care costs, and ultimately influence physicians’ quality outcomes and payment.

For instance, a 2021 JAMA study found social determinants of health were associated with more than a third of the geographic variation in Medicare’s per-patient costs (tma.tips/SDOHMedicareSpending).

In addition, in a March survey by The Physicians Foundation, eight out of 10 physician respondents reported the U.S. couldn’t improve quality outcomes without addressing these nonmedical factors. The same portion believe social determinants of health contribute to physician burnout.

“Sometimes a patient may not get better, through no fault of the patient and through no fault of the physician,” said Robert Seligson. He is CEO of The Physicians Foundation, which for more than a decade has advocated for payers to address these risk factors, with physicians leading the charge on that advocacy.

“If we’re going to talk about patient care, then who best to push measures that … actually help improve our patients’ well-being, and who better to talk to lawmakers than our physicians?” Mr. Seligson said. “These doctors love their patients, and they want their patients to get better. If these issues aren’t addressed, their patients don’t improve … and that puts stress on doctors.”

The two social-determinant quality measures CMS is considering are:

- Screening for Social Drivers of Health, which would record the percentage of adult patients screened for food insecurity, housing instability, transportation problems, utility needs, and interpersonal safety; and

- Screen Positive Rate, which would record the percentage of patients who screen positive for those factors.

The Physicians Foundation worked to ensure these voluntary quality measures, if approved, are beneficial to physicians and not administratively burdensome by lobbying CMS to remove an equal number of quality measures from physicians’ reporting requirements.

Although these quality measures are still under review, the billing codes with which they would work in concert are already in the pipeline, says San Antonio radiologist Ezequiel “Zeke” Silva, MD. He chairs the American Medical Association/Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), a volunteer panel that advises Medicare on its physician fee schedule, focusing in large part on how shifts in science and technology should affect payments.

In recent years, RUC has restructured existing billing codes and added new ones to allow physicians to report social determinants of health-related diagnoses and bill for the greater time spent identifying them or for the greater medical decision-making required.

Physicians then could use the additional revenue to continue screening and find ways to connect patients to support services, Dr. Silva says. At the same time, CMS could use the screening data to identify trends and develop targeted solutions.

For instance, the CMS Innovation Center, which supports the development and testing of innovative health care payment models, recently updated its strategic objectives to include advancing health equity (tma.tips/CMSStrategicRefresh). All new payment models will require participants to collect data on social determinants of health, among other demographic information, and to set targets for reducing inequities at the population level.

“If you can address problems with patients at a socioeconomic level before they become medical conditions at the individual level, then the economic benefit of that is obvious,” Dr. Silva said.

New Medicaid initiatives

Texas Medicaid is on a similar path.

With endorsement from TMA and the Texas Pediatric Society, Tyler pediatrician Valerie Smith, MD, and Austin pediatrician Marjan Linnell, MD, in February 2020 submitted a new state Medicaid benefit proposal to pay physicians for food insecurity screenings.

At her small, low-cost practice, Dr. Smith has seen parents dilute baby formula to make it last longer, which can lead to acute medical problems. Other families live in food deserts, and so they rely on fast food restaurants for many of their meals, often fueling diabetes and obesity in their children.

“Our experiences in clinic [lead to] our real deep understanding that food insecurity is connected to health outcomes for our patients,” she said. “We do not have all of the solutions to the health challenges that our patients face within our clinic walls, but we need to help address, when we can, these things like food insecurity.”

Dr. Smith’s practice uses grant funding to employ a social worker, who helps link patients who screen positive for food insecurity to resources, like the local food bank. The Medicaid payment would provide a long-term, sustainable revenue stream to maintain this service.

HHSC is considering the proposal. If implemented, this policy change is part of a series of social-determinant initiatives the state is required to offer under its Medicaid 1115 Transformation Waiver, which helps fund Texas safety-net hospitals and their affiliated clinics, says Helen Kent Davis, TMA’s associate vice president of governmental affairs.

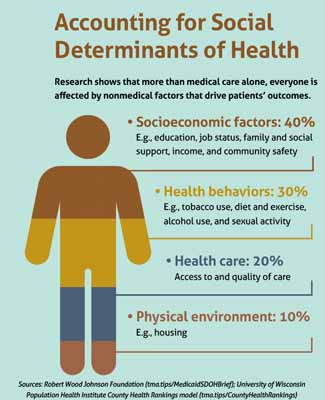

A February 2019 brief by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation points out that state Medicaid programs are fertile ground for testing social determinants of health interventions, especially amid the shift to value-based care (tma.tips/MedicaidSDOHBrief).

“Medicaid enrollees – low-income by definition – are particularly likely to struggle with basic needs,” the report says. “With state Medicaid programs increasingly looking to pay for health outcomes – and not simply the volume of health care services delivered – there is an increased focus on strategies to address social needs that contribute to outcomes.”

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic also has highlighted the need for such interventions, given widening health disparities across racial and ethnic groups, Dr. Smith adds.

Meanwhile, in the absence of a blanket directive from the state, Medicaid managed care plans are opting to develop their own initiatives, Ms. Davis says. Generally, their goal is to identify, using data, which initiatives are the most effective at improving health outcomes and lowering costs.

For instance, Driscoll Health Plan takes a triple-pronged approach with its South Texas patients by:

- Screening patients enrolled in care management for social risk factors;

- Developing local partnerships, such as partnering with Hidalgo and Cameron counties to open two community centers, where patients can access free health education; and

- Launching targeted programs to address specific issues, such as food insecurity and social isolation among pregnant patients at high risk of developing gestational diabetes.

Driscoll Chief Medical Officer Karl Serrao, MD, says this strategy is a new frontier for the health plan.

“We’re being asked to look at health through a different lens,” the Corpus Christi pediatrician said. “Traditionally, we have looked at it through the typical lens of medicine: hospitals, office visits, medicine, surgeries.”

And physicians remain central to this holistic approach, he said.

Payers rely on physicians and their staff to conduct the social determinants of health screenings and connect patients who screen positive to the health plan’s programs. Once Driscoll has gathered more data and identified best practices, Dr. Serrao says it intends to use its cost savings to pay physicians for these services.

“We cannot do this without the physicians,” Dr. Serrao said. “As a health plan, it’s kind of tough to earn the trust of folks. They very often trust their doctors.”

The more payers incentivize screenings, the less stigma such screenings will carry – and the more effective they’ll be at identifying social risk factors early, adds Feba Thomas, MD, family physician at People’s Community Clinic in Austin. The federally qualified health center has standardized the screening process by placing a QR code in each exam room that pulls up a social determinants of health questionnaire in English or Spanish and allows for quick responses and interventions.

“We’ve seen a significant effect and very grateful patients,” she said. “It’s nice to see [payers] catching up to the work [we’re doing] and to the need of our population.”

Tex Med. 2022;118(5):22-25

May 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page