In addition to the devastating COVID-19 surge fueled by the delta variant, pediatricians like Valerie Smith, MD, and other specialists caring for children point to a shadow pandemic among young patients.

The proportion of mental health-related visits for children aged 5 to 11 and 12 to 17 increased 24% and 31%, respectively, between mid-March and October 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Anecdotally, those figures are on the rise.

“This last year has been really unusual in that we’ve been seeing fewer of what we call bread-and-butter pediatric issues,” Dr. Smith said, citing respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), flu, and ear infections. “We definitely saw an increase in the number of children dealing with mental health issues.”

Taken together, COVID-19 and behavioral health needs have transformed her Tyler practice, which mostly serves patients enrolled in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

While training 20 years ago, Dr. Smith says the diagnosis and treatment of behavioral and mental health conditions in children were typically considered the purview of pediatric psychiatrists. But they're increasingly a part of her day-to-day work, which now includes medication management and frequent use of the Child Psychiatry Access Network (CPAN). (See “Making the Right Call,” page 26.)

Although Dr. Smith has grown more comfortable and adept at meeting her patients’ behavioral and mental health needs, she is filled with worry: for her patients whose preexisting anxiety and depression have spiraled during the pandemic; for those who lack the safe, stable, and nurturing relationships with adults that can help insulate them from the long-term effects of trauma; for the social butterflies who have been isolated from peers, educators, and school-based counselors; and for the families who cannot afford to take time off work or access inpatient psychiatric treatment.

Already, the pandemic has been linked to social isolation; increasing rates of substance use, domestic violence, and evictions; and countless deaths – all of which may contribute to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

“The challenge with the behavioral health struggles is that it’s often months and months, if not years and years, before issues are resolved,” she said.

And with the summer COVID-19 surge landing a higher proportion of children and adolescents in Texas hospitals, plus the return to school and the infections it brings, physicians caring for kids also are feeling the stress of a seemingly never-ending pandemic that has overwhelmed hospitals and strained staff.

“This has been a really difficult stretch for pediatricians and everyone involved in children’s health care here in Texas,” said James Versalovic, MD, the pathologist-in-chief and interim pediatrician-in-chief at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Double whammy

Coupled with the increased demand for behavioral health care, pediatricians, family physicians, and others specializing in pediatric care have faced a sharp increase in the number of young patients testing positive for COVID-19 and requiring hospitalization – placing pediatric practitioners under their own cloud of stress.

Between mid-August and mid-September, six of Dr. Smith’s patients were hospitalized with COVID-19, compared with two during the first 16 months of the pandemic. Because there is no pediatric ICU in Tyler, those patients often get transferred to hospitals elsewhere in Texas or out of state.

The delta variant grew dominant shortly after the COVID-19 vaccines were approved for children 12 and older in May 2020, meaning that many were partially or not yet vaccinated and susceptible to the virus. There was also an RSV surge, which left many infants and very young children hospitalized – some with COVID-19 co-infections. Meanwhile, children were returning to school, and families were catching up on appointments and procedures they had put off earlier in the pandemic.

“The timing issue cannot be overemphasized,” Dr. Versalovic of Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston said. “We’ve had to make some tough decisions in terms of prioritizing care during the delta surge.”

Dr. Versalovic also worries about the flu season, which could converge with the delta variant to produce what he called a “twindemic,” and pile onto the behavioral health challenges associated with long

COVID.

A new kind of ACE

At the same time, many children are less insulated from adverse childhood events because the pandemic has eroded certain protective factors, such as positive peer networks and household financial stability, says Coppell pediatrician Angela Moemeka, MD.

The term adverse childhood experiences covers a wide range of stressful childhood events, including abuse, neglect, and the loss of a parent or caregiver, many of which have increased during the pandemic.

The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, a multidisciplinary, multi-university collaboration established in 2003, coined the term “toxic stress” to describe the effects of an excessive stress response on a child’s developing brain, immune system, metabolic regulatory system, and cardiovascular systems. ACEs can trigger such a response; multiple ACEs can put a child’s stress response into overdrive, “like revving a car engine for days or weeks at a time,” according to the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University.

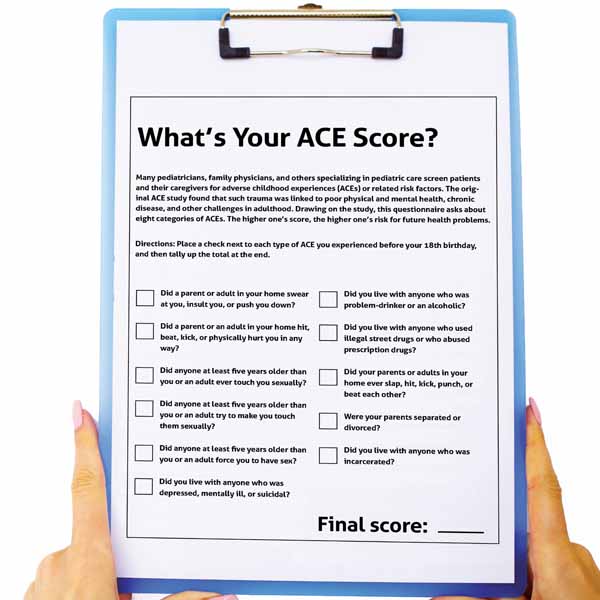

The consequences of multiple ACEs – and the toxic stress that accompanies them – can diminish quality of life and accelerate death. But pediatricians and other physicians can help interrupt ACEs by screening for them or associated risk factors; connecting patients to community resources; and strengthening protective factors, such as household financial security and healthy relationships. (See “What’s Your ACE Score?” page 35.)

Dr. Moemeka uses Safe Environment for Every Kid, or SEEK (tma.tips/seekscreen) – a brief parental screening tool that can identify certain risk factors for ACEs – and offers referrals to community-based organizations that can provide resources. She also uses CPAN.

Such interventions can help mitigate the long-term effects of ACEs, which are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance use problems in adulthood, according to CDC.

But there is no silver bullet, Dr. Moemeka says. “The ACE that every child is going to check off on the box is the pandemic.”

Ultimately, her goal is to prevent ACEs from occurring rather than responding after they’ve developed.

Physicians and experts stress that the long-term effects of ACEs aren’t predetermined.

Austin pediatrician Kimberly Avila Edwards, MD, spends one half-day a week at the Dell Children’s Medical Center mobile clinic, which serves uninsured children. School closures and virtual learning have prompted some of her patients to strengthen relationships with the adults in their lives, which can help insulate them from the long-term effects of ACEs. But others have been destabilized by the pandemic.

In a July report (tma.tips/cdcjointreport), CDC, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the World Bank, the World Health Organization, and four universities estimated that at least 136,692 children in the U.S. had lost a primary or secondary caregiver to COVID-19. The death of a parent is itself an ACE; safe, stable, nurturing adult relationships are one of the most-often cited protective factors. Such a loss can also introduce new adversity if the parent was a breadwinner or if the death displaces the child.

“Unfortunately, we have had to walk with our kids through that,” Dr. Avila Edwards said.

Dr. Avila Edwards has also noticed an uptick in mental illness among her patients. Sometimes, all the patients she sees in clinic are there for mental health issues, which she didn’t expect going into general pediatrics. “In terms of mental health, it’s so important to remember that we were already seeing an increase [in demand] prepandemic,” she said. “Things have definitely gotten even more acute in terms of need and, no question, worsened.”

Over the course of the pandemic, Dr. Avila Edwards has grown more dependent on state resources, such as CPAN, and more vocal when it comes to advocating for state- and federal-level policy changes that can help strengthen pediatric behavioral and mental health care resources.

During the 2021 regular legislative session, state lawmakers passed several Texas Medical Association-supported public health measures, including a $339 million increase in behavioral health funding and important telemedicine advancements. Medicine continues to advocate for other important asks, including health care coverage expansion and permanent telemedicine payment parity. (See “Physician-Led Results,” August 2021 Texas Medicine, pages 20-39, www.texmed.org/PhysicianResults.)

Tex Med. 2021;117(11):34-38

November 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page