Timothy Benton, MD, was elated when in January 2020 a consortium of West Texas oil companies offered $5.9 million to kickstart 21 new residency positions at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC)*. That’s because the department chair and associate dean of clinical affairs at the medical school knows creating residency positions helps erase Texas’ large and growing physician shortage.

Dr. Benton and his staff already had expanded the TTUHSC family medicine residency program from six to 48 positions between 2012 and 2020. Much of the school’s effort focused on putting residents in settings where doctors are scarce – such as community psychiatric centers and small rural hospitals. (See “Rural Residencies,” December 2018 Texas Medicine, pages 32-37, www.texmed.org/RuralTraining.)

Those efforts caught the oil consortium’s attention, allowing TTUHSC to boost its total number of residencies to 69, Dr. Benton says.

“[They] recognized we’re moving forward and advancing primary care, engaging in the community, and that our residents are staying in the region and populating the region,” he said. “This [funding] would be hard to replicate in other cities probably. Not everybody’s got the petroleum industry in their backyard. But I believe that through community engagement there is opportunity [to expand GME] in a lot of places.”

That kind of gift stands out, in part, because funding for graduate medical education (GME) usually comes not from private sources, but from the federal or state levels, or from hospitals, Dr. Benton says. (See “Growing Residents,” June 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 42-45, www.texmed.org/GrowingResidents.)

In 2019, Texas had 648 residency programs – a 29% jump since 2009, according to data compiled by the Texas Medical Association’s Medical Education Department. And state funding has supplied much of that growth, says Stacey Silverman, PhD, assistant commissioner of the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB).

In the 2020-21 biennium, state lawmakers approved $157 million in GME funding, up from $97 million in the previous biennium. Part of that money goes to state grants TMA championed to pay for new residency slots. In all, the state has helped fund 2,171 residencies, including 390 first-year positions, she says.

But the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic has thrown future GME growth into doubt. Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar projected in January that the pandemic had turned an expected surplus of about $3 billion into a deficit of nearly $1 billion.

In response, state GME funding of $157 million from 2019 may be cut back 5% to $150 million for the 2022-23 budget, Dr. Silverman says.

TMA is pushing lawmakers to at least maintain the current number of state-funded residency positions, which would require $195 million in 2022-23, according to THECB figures.

In addition, a 2017 state law backed by TMA, Senate Bill 1066, requires all new publicly funded medical schools to ensure there are enough residency positions in the state to accommodate the school’s expected number of medical graduates. As of this writing, proposals under consideration by the Texas Legislature for 2022-23 didn’t provide funding for any grants to create GME positions, which could stunt needed growth.

Without adequate monies, GME programs across the state will face cuts, or hospitals will be forced to fund the positions themselves – an unlikely possibility, says Woodson “Scott” Jones, MD, vice dean of GME for the UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine.

“We would see GME program closures and many lost GME positions at a time we cannot afford to have them,” said Dr. Jones, a pediatrician.

Most training programs last a minimum of three to four years, but the biennial state budgets support only two years of funding at a time.

“If [lawmakers] keep the funding flat and they come back to us next year and say, ‘I’m sorry we’ll still fund those first two years, but we’re not going to fund years three and four,’ I can’t pull that money out of a hat,” Dr. Jones said. “The take-home point that I’ve made to my dean is that, I get it that we may not see any expansion in new first-year training positions from the legislature. However, if they don’t increase funding to finish what they started, we can’t even sustain the last biennial gains in GME positions.”

The Medicare bottleneck

Medical students who do their residency training in Texas have an 80% likelihood of staying and practicing medicine in the state, Dr. Silverman says. So if Texas places most of its medical school graduates into in-state residencies, that will take a big bite out of the state’s physician shortage. (See “Texas Residents and the Physician Shortage,” left.)

On the other hand, too few residency positions creates a bottleneck that keeps the Texas physician workforce from growing, says Marcia Collins, TMA associate vice president for medical education.

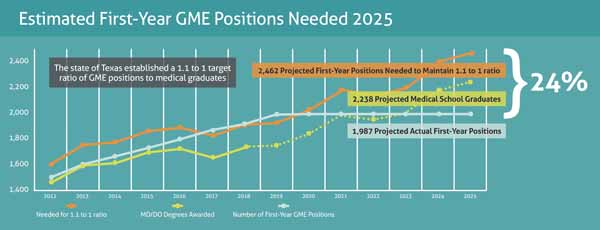

The number of Texas medical school graduates is rising, with nearly 2,000 expected to receive a diploma in 2023, up from 1,700 in 2018, according to TMA data. Without enough residencies, those young physicians will head off to other states once they graduate.

“We know from our graduate surveys that most students who end up leaving the state for residency would have preferred to be matched to a residency program in Texas,” said Lisa Nash, DO, associate dean for education programs at the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNTHSC) Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine in Fort Worth.

Texas currently spends $381 million per year on medical students, or about $45,000 per student, according to TMA research. So each Texas student lost to another state also represents a lost investment, Ms. Collins says.

Texas’ physician shortage has deep roots in the U.S. Balanced Budget Act passed by Congress in 1997. It froze U.S. residencies funded through Medicare at 1996 levels despite population growth since then.

The December 2020 stimulus bill passed by Congress provided a small break in that ice. It funded 1,000 new Medicare-supported residency positions over a five-year period – the first increase in Medicare-funded GME in nearly 25 years, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

But it remains unclear how many positions – if any – Texas will receive, and this tiny increase could be used by state lawmakers as an excuse to withhold state spending on GME.

“One of our biggest risks is that they’ll take a look at that and say the federal cavalry is coming to pay,” he said.

Since most federal GME money comes from Medicare, these mostly frozen levels dominate every aspect of how medical schools and hospitals create residencies, Dr. Nash says.

There are two types of hospitals – those with existing residency programs and so-called “naive” hospitals that have yet to set up residency programs, she explains. Each type of institution must approach creating GME spots in very different ways.

Those that already have residency programs “are [probably] never going to get any more money from [Medicare] for residency than they’re getting right now,” Dr. Nash said of those hospitals. “So if they decide they want to grow any of their GME programs or start a new one, they’ve got to find that funding somewhere other than the feds. It’s either coming from the [state] or they’re finding some way to put that in the hospital budget.”

Since 2014, thanks in part to TMA advocacy, Texas has provided expansion grants for existing hospital GME programs looking to boost the number of positions. The grants pay $75,000 of the $150,000 most studies show is required to pay for one residency spot, Dr. Silverman says. That $150,000 covers all annual costs – benefits, health care, salary, and other related expenses. U.S. resident salaries alone average $58,921 annually, according to the Academy of American Medical Colleges.

Even in those rare cases when private funds help pay for residency spots, that funding is usually temporary because GME is so expensive, Dr. Benton says. For instance, the oil consortium’s donation to TTUHSC will last only until 2025. After that, the medical school will have to replace it with a combination of expansion grants and hospital funding to keep the residencies going, he says.

Naïve hospitals, the ones with no GME programs, are eligible for new Medicare GME funding for the residency spots they create. But many hospitals get caught off guard by the fact that the number of Medicare-funded GME positions will be capped after five years, Dr. Nash says. After that, those GME programs can only add positions by paying for them in another way.

Many hospital administrators understandably want to start off with a small residency program and build slowly, Dr. Jones says. But it’s smarter to plan immediately for all the residency positions the hospital will need in coming decades, not just the next year or so.

“One of the biggest hospital systems here in [San Antonio] made the mistake of starting a small GME program a number of years back that had one to two positions in it,” he said. “That is now where they are limited on what their [Medicare] reimbursement will be,” he said. “Their ability to draw down more [federal] GME funding is severely limited.”

Starting from scratch

Starting from scratch

Dealing with Medicare’s five-year cap is just one of many challenges to starting a residency program, Dr. Nash says. And although Texas’ 2017 state law does not directly affect private schools like TCU-UNTHSC or older public medical schools like TTUHSC, it does pressure them to create slots to keep up with the other schools.

With administrative support and procedures already in place, existing residency programs usually just need to secure funding when they want to add GME slots, Dr. Nash says. But creating a GME program involves a lot of work for both medical schools and the hospitals involved.

For that very reason, the state offers GME planning grants of $250,000 per recipient to help naïve hospitals through the assessment phase, among other issues. But like expansion grants, planning grants face the prospect of legislative cuts – in this session 4.3%, says Ms. Collins, TMA associate vice president of medical education.

Dr. Nash says the first thing a medical school can do is make contact with hospital leadership to find out if they’re even willing to talk about it. “And if you can get to that point then the next step might be to take the pulse of the medical staff and find out if you have enough people who are potentially interested in teaching.”

If everyone agrees, then they take an inventory of the hospital resources and patient growth patterns to determine, for instance, which specialties would best fit the staff and the patient base. After that, the hospital typically hires a consultant to assess the financial requirements of starting a residency program, Dr. Nash explains.

“Hospitals, especially rural hospitals, cannot afford to lose money on GME,” she said. “The math just has to work.”

Hospital administrators also must hire a residency director and train staff to prepare for educating physicians. Any new residency program faces a lengthy accreditation process from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (tma.tips/ACGMEaccreditation).

In many cases, small hospitals – the ones most likely to lack a residency program – don’t have the administrative experience to quickly handle all these new duties, Dr. Nash says.

“That’s certainly a skill set that most business offices for rural and community hospitals don’t have,” she said. “It’s probably most common for them to have a [partnership] with an academic medical center [to help with those duties].”

Despite these obstacles, hospitals gain a lot from becoming a training institution, says JoAnna Leuck, MD, assistant dean for curriculum at the TCU and UNTHSC School of Medicine in Fort Worth.

For instance, a Jan. 28 JAMA Open Network study of 1,298 academic hospitals found that more GME funding led to reduced patient mortality (tma.tips/JAMA-GME).

“If you look at the literature, there’s definitely a trend toward improved outcomes and practicing cutting edge medicine by training facilities,” said Dr. Leuck, an emergency physician. “You have these residents who are really pushing to learn the most up-to-date information, to make sure they have the newest technologies to be ready for their own practice. And that pushes the institution as a whole.”

Economic realities

Before states like Texas began funding GME expansion programs, most residency growth occurred in subspecialty training, Dr. Jones says. Texas’ population needs call for more primary care physicians, but the relative expense of training them compared with training subspecialty physicians has been prohibitive.

“If you think about internal medicine, you have to have your general internal medicine faculty, but you also have to have to hire a broad array of subspecialists [on the faculty] to help educate those [internal medicine] trainees,” he said.

In addition, hospital mergers have changed physician employment prospects throughout Texas, and that includes residencies, Dr. Nash says. She recently worked with a hospital owned by one health system that started a GME program and planned to include future growth. But those plans changed abruptly once another chain bought the hospital. The new owner kept the existing residencies but halted any new positions.

“These are all for-profit corporations, so it depends on their markets and what their financial strategies are,” she said.

Rural residency programs face even more unpredictability – but also greater need, Dr. Benton says. TTUHSC’s residency program feeds a rural training track that sends two residents apiece to six rural hospitals in West Texas, a region short on primary care.

That directly benefits the state’s financially shaky rural hospitals, he says. Texas leads the nation in rural hospital closures with 26 since 2010, and many more are financially vulnerable, according to the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals.

Residents are less expensive to pay than other physicians, and in small rural towns they offer some promise that health care will improve.

“The hope is that [the residents] graduate and stay,” Dr. Benton said. “Then you continue to multiply the primary care workforce over the region.”

*The original story said a consortium of oil companies offered $5.9 million to kickstart 21 new residency positions at "Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Lubbock." The name of the school should have read "Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center."

Tex Med. 2021;117(4):20-25

April 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page