Vaccine scientists normally toil in anonymity, spending years nursing their creation through a series of regulatory and financial hurdles before finally earning a license from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

But not in 2020. Creating a vaccine for COVID-19 has become the world’s top priority, so vaccine development is suddenly moving very fast in a high-profile way, says Charles Andrews, MD. He is director of clinical research at Diagnostics Research Group in San Antonio, which is carrying out clinical trials for the COVID-19 vaccine backed by Pfizer.

Most people understand that quickly making a safe, effective coronavirus vaccine is one of the best hopes for stopping or slowing the pandemic, he says.

“This is unquestionably the most important [clinical] trial I’ve ever worked on,” said Dr. Andrews, who has worked on more than 300 other medical studies, including those for the Shingrix shingles vaccine.

Vaccine makers face intense scrutiny. The pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca made front page headlines in September when it unexpectedly hit the brakes on developing its COVID-19 vaccine. A United Kingdom volunteer taking part in its Phase III trial suffered an adverse reaction, and the trial was halted briefly and then resumed after an investigation, according to news reports.

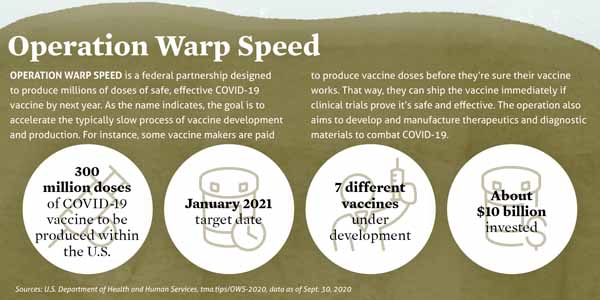

Vaccine makers also face an intense timeline. AstraZeneca’s and Pfizer’s vaccine candidates are part of Operation Warp Speed, a U.S. government initiative designed in part to deliver 300 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine by January 2021. (See “Operation Warp Speed,” page 18.)

It’s called “Warp Speed” because producing a vaccine from start to finish typically takes 10 to 15 years. Before COVID-19, the record for development and production went to the vaccine for mumps, which clocked in at four years in the 1960s.

Compressing that down to one year or less is not the ideal way to produce a vaccine, says Peter Hotez, MD, professor of pediatrics and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. He is also co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, which is developing a COVID-19 vaccine that began clinical trials in September.

Fortunately, vaccine makers are well-acquainted with coronaviruses, and the obstacles can be overcome safely even on a shorter timeline, he says.

“It is harder, but it’s doable and it seems to be happening,” Dr. Hotez said in September. “[The accelerated timeframe] doesn’t give me pause as long as we adhere to the well-crafted regulatory framework for how we prove and license vaccines. As long as we follow standard practices as outlined by the Food and Drug Administration, I think we’ll be fine.”

Vaccine makers appear to be doing just that, says Alan Barrett, PhD, director of the Sealy Institute for Vaccine Sciences at The University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.

About 300 COVID-19 vaccines are in production worldwide, he says. While some scientists have criticized vaccine developers for not releasing their protocols and data to the public, Dr. Barrett says they have been largely transparent about their findings with each other – the people best-equipped to review the data. This openness is unusual among competing companies and organizations in vaccine development, and he sees “no evidence that corners have been cut” in testing or safety.

In September, public pressure from the American Medical Association and independent vaccine scientists for greater transparency prompted vaccine makers to provide details about their products. In an unusual move, the companies producing three major COVID-19 vaccines released the protocols of their trials, outlining their expectations for participant enrollment and benchmarks for vaccine efficacy, according to Medscape.com.

Also, the effort to produce a COVID-19 vaccine has benefited from an unprecedented shift in both funding and scientific brainpower toward solving this problem. The creation of a COVID-19 vaccine is frequently compared to other pathbreaking scientific projects like the effort to produce a polio vaccine in the 1940s and 1950s, and the space race of the 1950s and 1960s between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

“The confidence level is very high,” said Mezgebe Berhe, MD, an infectious disease specialist in Dallas. He is the lead vaccine investigator for North Texas Infectious Disease Consultants, which is handling clinical trials for vaccines produced by Pfizer and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. “The reason I say that is medical technology, medical research is in a better place than it has ever been. The platforms and medical technologies were not there [even in the 1990s].”

The same steps faster

Despite that confidence, many people not involved with the vaccine-making process are concerned about the speed at which COVID-19 vaccines are being developed, says family physician Gretchen Crook, MD, principal investigator for Austin Regional Clinic (ARC) Clinical Research, which is participating in the clinical trials for the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine.

She compared it to a separate study ARC is conducting for Pfizer’s C. difficle vaccine.

“Every step of the process is almost identical as far as the timeline and monitoring, having the patients come back and tell us about any side effects or illnesses,” Dr. Crook said. “Everything is the same. There isn’t anything rushed about any of that.”

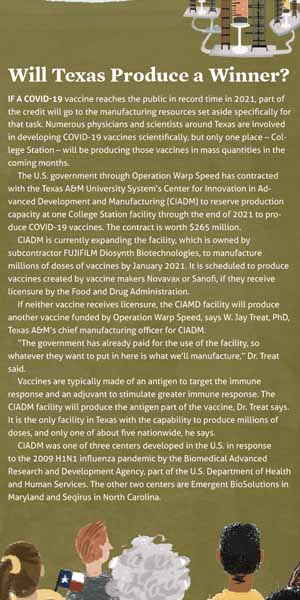

And yet everything about the COVID-19 vaccine is being done with greater urgency. Even before clinical trials began, vaccine makers quickly won regulatory approvals that previously took months or years, Dr. Andrews says. Also, they have been able to take many steps – like development and manufacturing – at the same time. (See “Will Texas Produce a Winner?” page 20.)

And yet everything about the COVID-19 vaccine is being done with greater urgency. Even before clinical trials began, vaccine makers quickly won regulatory approvals that previously took months or years, Dr. Andrews says. Also, they have been able to take many steps – like development and manufacturing – at the same time. (See “Will Texas Produce a Winner?” page 20.)

That urgency has been apparent in the clinical trials as well, Dr. Crook says. For instance, in a normal vaccine study, patient data received on Monday might not be sent to the pharmaceutical company until later in the week. For the COVID-19 study, it must be entered by the end of the day.

Normally, pharmaceutical companies would not be able to handle working at such a rapid pace, Dr. Crook says. But now all the money and resources used to produce a vaccine over 10 or 15 years have been focused into a few months.

“[Pfizer staff] have been working around the clock trying to get this developed,” Dr. Crook said. “They are also asking the investigators to take that much attention. … They’re available on the nights and weekends if you have to call or have any questions. It’s just a lot more resources for a lot more people to get the work done.”

In screening participants for a Phase III clinical trial, vaccine makers have physicians rule out anyone who tests positive for COVID-19, anyone with a compromised immune system (like those with lupus), or those who take immunosuppressant medications like steroids, Dr. Andrews says. (See “Talk to Patients About: Vaccine Testing,” page 23.)

However, vaccine makers also want to find volunteers who are in a position to catch the disease and those who are vulnerable to serious symptoms, he says. For instance, his company signed up 54 front-line health workers, including 25 physicians, for the Pfizer Phase III clinical trials.

Focusing Phase III clinical trials on high-risk groups allows vaccine makers to show that a vaccine can protect anyone against the disease. All participants give informed consent and understand that half of them will receive the real vaccine and half will get a placebo, Dr. Andrews says.

In most vaccine trials, locating the right volunteers can be “like searching for a needle in a haystack,” he said. But recruiting volunteers for the COVID-19 clinical trials has not been a problem.

“The trial participants have mostly found us because they like the opportunity to get a real vaccine,” he said. “For all studies, we pay people for their time and travel. Interestingly, for the COVID trial, a lot of persons have said they’re not even interested in getting paid. That’s very unusual for us.”

Other physicians report similar enthusiasm. For instance, ARC Clinical Research has recruited people in the Austin area on behalf of the Pfizer vaccine, Dr. Crook says.

“Normally, 15% of those qualified patients we speak to also agree to participate in a vaccine trial,” she said. “But for the COVID-19 vaccine, 88% of those qualified agreed to participate.”

Reaching everyone

Despite such enthusiasm, one important swath of people – racial and ethnic minorities – have been difficult to recruit, Dr. Berhe says. Their participation is important because numerous studies show that they become ill with COVID-19 at unusually high rates.

Unfortunately, Latinos and Blacks have a long history of mistrusting medical professionals, and their representation in the medical profession is disproportionately low.

(See “An Unfortunate Legacy,” September 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 18-23, www.texmed.org/UnfortunateLegacy.) Among other things, this has translated into low participation in medical trials.

For instance, fewer than 5% of Black patients took part in trials for 24 out of 31 cancer drugs approved by the FDA between 2015 and 2018, even though they made up about 13% of the U.S. population, according to a report by ProPublica.

Pharmaceutical companies have tried to change this pattern by using targeted advertising and by having physicians talk directly with patients, Dr. Berhe says.

“We want to see more minorities signing up for the vaccine [trials],” he said. “I think there is still a perception issue. In the hospital, I’ve spoken with a number of people who are at high risk of getting COVID-19, and they are simply reluctant to enroll.”

Texas frequently gets chosen for medical trials in part because it’s such a diverse state, making it easier to recruit Latinos and Blacks, Dr. Crook says. In the ARC Clinical Research COVID-19 vaccine trial, the number of people in those groups remain unrepresentative compared to the population. Nevertheless, “it’s definitely better than what has historically been the case” in ARC vaccine trials, she said.

Once COVID-19 vaccines are licensed by FDA, Texas physicians will be integral in convincing people to take them, Dr. Hotez says.

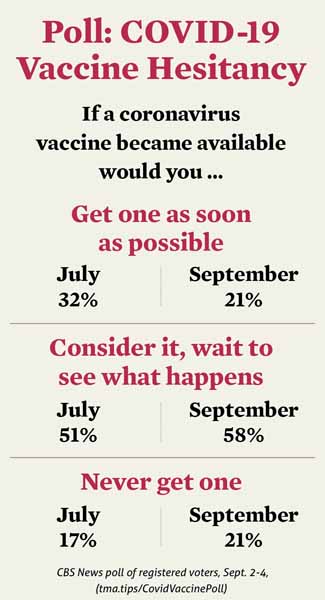

In a recent poll, most people surveyed said they would consider taking the vaccine but would wait to see what happens to others before getting one. (See “COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy,” page 21.)

This situation will be complicated by the fact that some vaccines will work better than others, while some will require boosters, Dr. Hotez says. Physicians must be ready to convey that information in ways that encourage patients to take the vaccines on schedule.

“Physicians and health care providers generally are going to need a lot of situational awareness to the fact that we’re going to be learning about these vaccines on the fly,” he said.

Race to the finish

In the U.S., the Operation Warp Speed vaccines appeared to be best positioned to receive an FDA license at press time in September. If any of them do, a vaccine might be available to the public by early 2021, Dr. Andrews says. But as the testing delay with AstraZeneca shows, vaccines can get stalled. If all the Operation Warp Speed vaccines fail to win a license, other vaccines will take a while to catch up, he says.

“They’re coming, but they’re going to be several months behind,” Dr. Andrews said.

In September, the U.S. government also was still drawing up plans to distribute a vaccine once one is licensed. Physicians and front-line health care workers are expected to receive some of the first doses. But logistical problems in storing and transporting the vaccines remained.

Texas’ experience may provide some guidance. In September, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) circulated a draft document designed to identify ways to equitably distribute a COVID-19 vaccine. It cited a plan created by the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) to respond to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (tma.tips/TexasH1N1Plan).

“A major success was the use of a public-private partnership, led by the DSHS, to allocate and distribute the vaccine to local jurisdictions, supported by the rapid implementation of a vaccine management system,” the NAM document said.

More than one COVID-19 vaccine likely will be needed to inoculate the world’s 8 billion people, says Dr. Hotez, especially since many vaccines are not designed for distribution in low- and middle-income countries. For instance, the Pfizer vaccine, if licensed, will require special super-cooled refrigeration equipment to be distributed.

“There’s really no one [among the Warp Speed vaccine makers] that’s specifically targeted a vaccine for people who live in poverty,” he said.

Some Operation Warp Speed vaccines also use technologies that provide immunity using messenger RNA. These vaccine technologies are promising, but they’re also unproven, Dr. Hotez says. And they are likely to have a high price tag and be financially out of reach for poorer countries.

The vaccine Dr. Hotez oversees uses a relatively simple technology based on recombinant protein, a technique already found in the hepatitis B vaccine. That means potentially it can be produced for as little as $1 or $2 per dose, he says. The Indian company Biological E has agreed to produce it if the vaccine proves safe and effective in clinical trials.

Many vaccines for other diseases have been shoved aside by vaccine makers in the effort to address the COVID-19 crisis, including vaccines for other coronaviruses, Dr. Hotez says. The world already has seen three major coronavirus pandemics since 2000 – SARS in 2003, MERS in 2012, and now COVID-19. Given that, he’s considering work on a more comprehensive coronavirus vaccine.

“[These pandemics] are happening every five or 10 years, and we should anticipate that another one will follow shortly after that,” he said. “It would be nice to have a universal coronavirus vaccine ready to go.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(11):16-21

November 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page