Infectious disease specialist Ogechika Alozie, MD, has a ready-made solution for patients diagnosed with hepatitis C now that five medications can rid patients of this deadly disease.

But for Texas Medicaid patients, there’s a catch. The program does not pay for the cure based just on a diagnosis. Instead, Medicaid pays only after a blood test, biopsy, or sonogram shows the liver is so badly damaged that it’s on the verge of cirrhosis.

At that point, patients who get the medication will be cured of their hepatitis C but more vulnerable to other deadly illnesses, like liver cancer, Dr. Alozie says.

He has told at least 100 patients in the past three years that he can’t cure their illness – at least not until their liver becomes more damaged.

“It’s ironic because Medicaid will pay for the visit and the workup, but then only for me to tell them, ‘Yes, you do have hepatitis C, and I could cure you, but Medicaid will not allow you to be treated.’”

The cure for hepatitis C remains out of reach for Texas Medicaid patients because of its price. Some of the first hepatitis C cures introduced in 2013 and 2014 cost $84,000 to $94,000, though prices have since fallen to the $20,000 to $35,000 range, according to the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (NVHR). But even these lower price tags force state governments and health insurers to rein in spending.

Hepatitis C medications are hardly the only high-priced medications that present problems for state Medicaid programs, says Lauren Canary, director of NVHR. But hepatitis C medications are some of the most urgently needed, and paying for them remains a national problem. Though many other states have eased these restrictions in recent years, Texas remains one of the strictest, she says.

These rules contradict recommendations by two leading medical authorities on hepatitis C: the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Disease Society of America (HCVguidelines.org). And they explain why Texas recently earned a D-plus grade from the NVHR and the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation of Harvard Law School (tma.tips/StateOfHepC).

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission, which oversees Medicaid, declined to comment for this article. In 2019, Texas lawmakers, with the support of the Texas Medical Association, passed a budget measure designed to explore a new method of making hepatitis C medications affordable for Medicaid patients.

But any changes that proposal might bring are several years away, and in the meantime, Texas Medicaid is required to focus on what is cost-effective, says David Lakey, MD, vice chancellor for health affairs and chief medical officer for The University of Texas System.

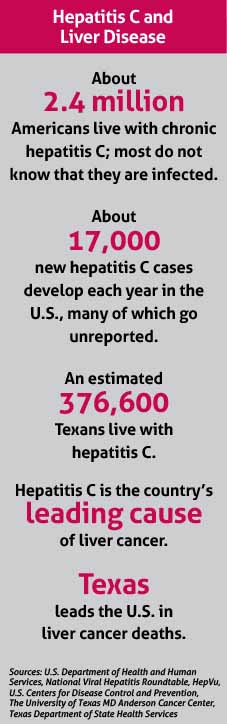

“That’s a challenge for things like hepatitis C, which – if left untreated over a long term – can result in liver failure and cancer,” said Dr. Lakey, a past chair of TMA’s Council on Science and Public Health. (See “Hepatitis C and Liver Disease,” right.)

Texas among strictest

Only three states – Arkansas, Montana, and South Dakota - have tighter rules than Texas on Medicaid coverage for hepatitis C medications, according to the NVHR-Harvard Law report card. Aside from the liver damage regulation, Texas Medicaid has two other prescribing restrictions:

• Only specialists in gastroenterology, hepatology, or infectious disease can write prescriptions; and

• The patient must be screened for substance use 90 days before submitting a prior authorization request for the medication.

The specialist requirement poses a hurdle for Texans in areas where there are few physicians, studies show. And the substance abuse restriction flies in the face of medical best practices, says Jason Gillman, MD, an infectious disease specialist in Dallas. Multiple studies dating to 2013 demonstrate that patients who use drugs achieve the same rate of cure as other patients, he says.

“All the scientific studies show those are the patients you should prioritize,” he said. “The patients using drugs are the ones who can transmit the virus to other people [by sharing needles].”

Physicians try to steer around the bureaucratic obstacles by obtaining the medications directly from drugmakers, but that can be time-consuming for doctors and patients, Dr. Gillman says.

“You basically have to game the system,” he said. For instance, “you still have to fill out the [Medicaid] prior authorization packet, the five or six pages, and then you get a denial. And then you have to file an appeal. And then you have to wait – it sometimes takes 30 days – and then you get the denial on the appeal. And if you get both denials and submit them to the manufacturer’s patient assistance program – which is another application packet – you can sometimes get the drugs for free from the manufacturer.”

Meanwhile, patients without Medicaid or insurance have to fill out only a one-page form and send it to the manufacturer, he says.

“It’s actually easier to treat someone who doesn’t have insurance at all,” he said. “It’s more work if the patient has Medicaid.”

The Medicaid restrictions also are outdated, Dr. Alozie says. Because hepatitis C medicine prices have dropped so sharply, it’s more economical to just pay for them rather than denying people access, Dr. Alozie says.

“Just like with every health condition, the sicker you get the more expensive it is for the system to manage,” he said.

The Netflix model

In 2015, Australia began experimenting with what’s called “the Netflix model” for buying hepatitis C medications. Just as Netflix charges a flat fee for unlimited viewing, this model calls for paying a flat fee to a drug company that supplies unlimited medications.

Since then, Louisiana and Washington state have adopted the model, and other states – including Texas – have expressed interest. In 2019, the Texas Legislature asked HHSC to explore the feasibility of the Netflix model and to prepare a report by July 1 on cost-effectiveness and projected savings.

“We also have an obligation to treat and cure our patients and stop this epidemic,” Dr. Lakey said. “So is there an effective way to get the best price that will allow us to treat and cure the most people possible?”

The Netflix model seems to offer many advantages. A February 2019 New England Journal of Medicine article estimated that Australia would save millions of dollars more than if it had used traditional pricing (tma.tips/NEJMNetflixStudy). The model is being hailed as an affordable way to give Medicaid patients access to other expensive medications as well.

However, not everyone is enthusiastic. Without the proper safeguards, paying pharmaceutical companies a flat rate could actually lock in higher prices for hepatitis C medications, according to an Oct. 25, 2019, Kaiser Health News article (tma.tips/KHNHepC).

But even if Texas HHSC reports favorably on this model, there is little the agency can do to improve funding for hepatitis C medications until lawmakers meet again in 2021, Dr. Lakey says.

“I don’t see [Texas Medicaid] relaxing those eligibility requirements until they have a way that they can effectively purchase these medicines,” he said.

For hepatitis C patients on Medicaid, that means having to check back in with their specialist every six months to have their liver monitored, Dr. Alozie says. They will need to get a new ultrasound as well as a blood test to see if their liver has become damaged to the point of being eligible for the cure.

The economic concerns about hepatitis C medications are understandable, Dr. Alozie says. Even at their reduced rates, they can be expensive, and more must be done about cost controls.

“But I also understand that I have patients who have hepatitis C who could be cured and that would stop the progression of the disease,” he said. “We’re waiting until it becomes end-stage when there’s a higher risk of morbidity and a higher risk of mortality, and to me it doesn’t make sense.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(2):38-42

February 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page