Ripple effects. That phrase comes up a lot when Texas physicians talk about the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), an agency whose future very much depends on a ballot proposition Texans will vote on in November.

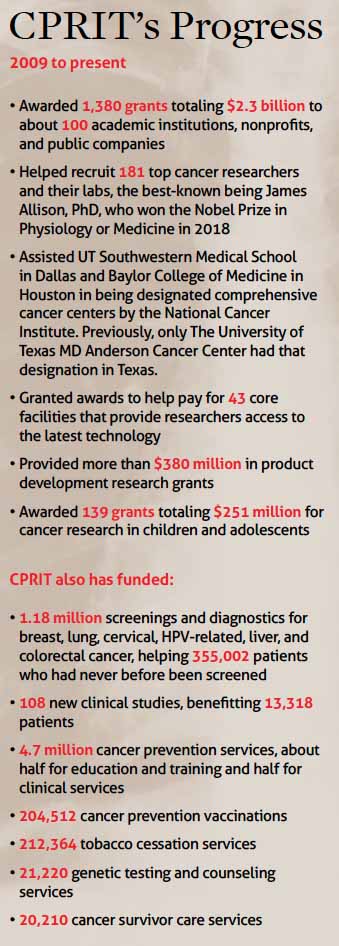

In the past 10 years, CPRIT has handed out $2.3 billion in cancer-fighting grants to Texas physicians and researchers; each of the 1,380 awards given to about 100 academic institutions, nonprofits, and public companies has sent ripples spreading throughout the state’s health care system.

For instance, thanks in part to CPRIT money, low-income Texans can get access to a cervical cancer screening program run by Marian Y. Williams-Brown, MD. She is an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin, which is partnering on the project with The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. The program brings screenings and treatment to parts of the state where cervical cancer rates are high, such as the Texas-Mexico border region and East Texas.

For instance, thanks in part to CPRIT money, low-income Texans can get access to a cervical cancer screening program run by Marian Y. Williams-Brown, MD. She is an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin, which is partnering on the project with The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. The program brings screenings and treatment to parts of the state where cervical cancer rates are high, such as the Texas-Mexico border region and East Texas.

“Because of CPRIT, health care providers are able to provide cancer screening and diagnostics, not only for cervical cancer, but for other cancers that can ultimately impact millions of Texans,” said Dr. Williams-Brown, who is chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Cancer.

CPRIT grants also have given Texas an edge in recruiting cancer researchers, says oncologist C. Kent Osborne, MD, director of the Dan L. Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“It’s been a lifesaver for us,” he said. “It’s allowed us to recruit new premier faculty to Texas and to our institution, people that we wouldn’t have been able to recruit otherwise.”

Other ripples are perhaps not as obvious, says Philip Huang, MD, director of Dallas County Health and Human Services. For instance, in recent years signs have appeared in institutions like UT Austin, saying they are “tobacco-free facilities.” Those policies came about as a direct result of CPRIT rules requiring that grant recipients adopt tobacco-free policies.

“There are a lot of other ripple effects that come from the CPRIT support that really impact the state,” Dr. Huang said. “Just think of the economic impact [of billions of dollars in grants] in terms of the investment in the community, and these efforts help support the state in multiple ways.”

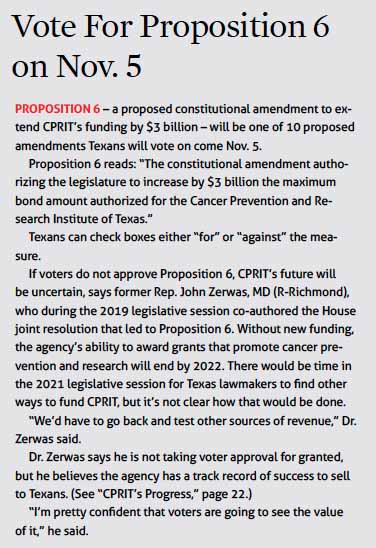

On Nov. 5, Texans will vote on Proposition 6, a constitutional amendment designed to extend CPRIT’s funding by $3 billion and keep the agency’s grants flowing for an estimated 10 additional years. (See “Vote for Proposition 6 on Nov. 5,” page 21.) TMA supports this effort to keep CPRIT’s current funding from running out in 2022.

“One of our priorities in terms of TMA and the Committee on Cancer is for physicians and all Texas voters to understand the important role of CPRIT in cancer prevention efforts in our communities and how important that funding is in the fight against cancer,” Dr. Williams-Brown said.

Those prevention efforts have saved money by avoiding the high medical costs of prolonged, often fatal illnesses, says Houston family physician Lewis Foxhall, MD, vice president of health policy at MD Anderson. More importantly, he says, they save lives.

“It’s hard to put a price on helping someone avoid getting cancer,” he said.

“CPRIT envy”

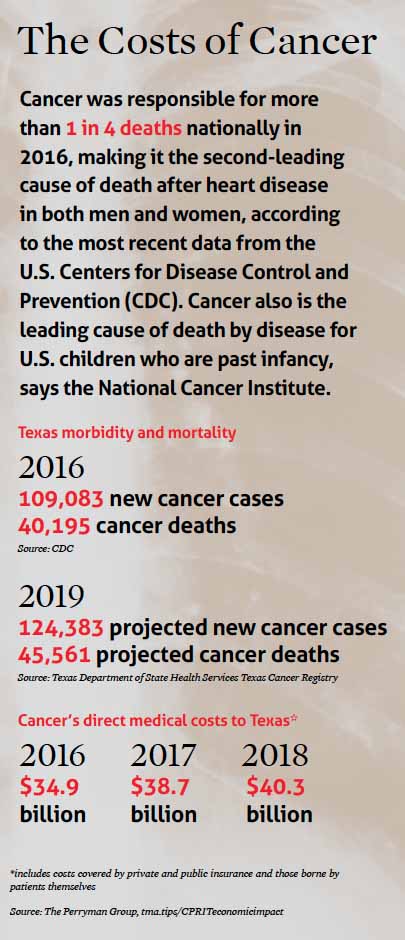

Cancer is a top public health priority nationally and statewide, and CPRIT was created to address it. (See “The Costs of Cancer,” page 23.) In 2007, Texas lawmakers and voters overwhelmingly approved $3 billion in taxpayer-funded bonds to start the agency. CPRIT began operations in 2009 and awarded its first grants in 2010.

The institute withstood serious scrutiny after three grants were awarded without proper peer review between May 2012 and January 2013. CPRIT was effectively shut down for 10 months. In 2012, CPRIT also got a new chief executive officer, Wayne Roberts, who has been in charge of the agency ever since.

“We underwent an exhaustive management audit by the state auditor’s office. We went through a trial [of a former CPRIT official who was found not guilty of fraud]. We went through an investigation by the attorney general’s office, and the legislature in 2013 reviewed our processes. They tightened some things down … and the legislature decided to give us another bite at the apple,” Mr. Roberts said.

CPRIT ultimately won back respect as the state’s top cancer-fighting institution. CPRIT dollars get split into three main areas:

• 72% goes to research, making CPRIT the second-largest source of cancer research dollars in the U.S. after the National Cancer Institute.

• 18% goes to improving the infrastructure for fighting cancer in Texas. This includes investing $380 million in product development research grants for new drugs and treatments, as well as providing funds to start or expand biotech companies and create more than 10,000 permanent jobs.

• 10% goes to prevention efforts, such as screening programs that detected more than 3,300 cancers and 16,200 cancer precursors, and giving many of these patients a chance to participate in clinical trials or studies.

CPRIT spends the lion’s share of its money on research, about $220 million annually for institutions of higher education alone. That’s something cancer experts nationwide notice, says Austin oncologist S. Gail Eckhardt, MD, inaugural director of the Livestrong Cancer Institutes at Dell Medical. She was recruited two years ago from outside Texas with a grant specifically designed to bring in established cancer experts.

“I had been in Colorado for the past 17 years, and I’m on advisory boards for cancer centers throughout the U.S., and virtually no other state has a CPRIT mechanism,” she said. “Those of us outside the state coined the term ‘CPRIT envy.’ That’s because we would review the funding and recruitment of people into other states, and it was way different when you looked at what Texas had.”

Jim Allison, PhD, is the state’s most notable recruit. Dr. Allison, who now works at MD Anderson, won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of a new approach to fighting cancer that goes beyond attacking the tumor. Instead it uses the immune system to fight cancer, leading to major advances in immunotherapy.

Most of these incoming researchers generate additional grants from the U.S. government and other sources, says Dr. Osborne from Baylor. So they add financial value to the institutions where they work as well as to the state’s economy.

“We invest in the researchers, and then they write their own grants,” he said. “And they’ve brought in to date about $1 billion in outside funding.”

Major medical, economic impact

CPRIT makes an even bigger financial splash by providing grants to more than 30 companies doing cancer research in Texas. For instance, Houston-based Bellicum Pharmaceuticals won a $16.9 million grant in 2017 after working with Baylor to develop a type of cancer immunotherapy in which some of the patient’s own T cells are removed, genetically modified, and reinjected into the patient to kill off cancer cells.

CPRIT makes an even bigger financial splash by providing grants to more than 30 companies doing cancer research in Texas. For instance, Houston-based Bellicum Pharmaceuticals won a $16.9 million grant in 2017 after working with Baylor to develop a type of cancer immunotherapy in which some of the patient’s own T cells are removed, genetically modified, and reinjected into the patient to kill off cancer cells.

The Bellicum drug is still in clinical trials in the U.S. and Europe. That helps explain why, despite all the money CPRIT has spent, it cannot yet claim to have funded any cancer cures or miracle drugs, Dr. Osborne says. All the rounds of testing and approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration take time.

“Even if somebody in the first year of CPRIT 10 years ago developed a new compound, it would probably just now be going into patients for the first time,” he said.

Even though many of the projects CPRIT funds are years from completion, the agency is proud of its outsized impact on the state’s economy. In 2018, The Perryman Group, a Waco-based economic analysis company, reported that CPRIT funding created $12.4 billion in Texas business activity as well as 110,265 new jobs directly and indirectly (tma.tips/CPRITeconomicimpact). CPRIT also generated $551.2 million in state tax income in 2018 and $249.8 million in local government tax revenue.

The same report estimated that ending CPRIT when its current funding runs out would cause a net cumulative economic loss of $141.7 billion to Texas, as well as a drop in state and local tax income of $6.6 billion and $3 billion, respectively.

CPRIT also has had a major impact on cancer prevention, says Dr. Foxhall at MD Anderson. The state’s premier cancer treatment center has received $18.5 million for prevention efforts tied to tobacco control; training and education; colorectal cancer screening; and other efforts, according to center. The colorectal screening program for instance, which has helped more than 10,000 patients, provides access to screening for those who would not normally get it, Dr. Foxhall says.

“Screening rates are low across the state, and in low-income and uninsured populations they’re very low,” he said. “Without programs like this, patients often just don’t get screened.”

In all, CPRIT-funded screening programs have identified 13,277 patients with cancer precursors and 3,364 with cancer, the agency says. Those programs also help people follow up on their diagnosis and get treatment.

Likewise, CPRIT funding helps pay for cancer survivorship programs, which counsel patients on how to cope with the changes cancer brings. Physicians across Texas can get trained by MD Anderson experts in how to provide help to cancer survivors through Project ECHO, a video conferencing initiative the cancer center uses. (See “ECHO-ing Across Texas,” February 2019 Texas Medicine, pages 44-46, www.texmed.org/ECHO.)

While cancer is the second-leading cause of death in the U.S. and Texas after heart disease, by funding an anti-cancer agency Texas actually is attacking both of these health problems at once, Dr. Foxhall says.

“Some of the primary drivers of cancer risk are the same as for cardiovascular disease,” he said. “Tobacco use, [poor] diet, and [lack of] physical activity – those are multiple-opportunity offenders.”

Without CPRIT, many of these prevention programs would disappear, Dr. Foxhall warns.

“The biggest challenge we have in prevention is lack of other sources of funding,” he said. “Fortunately, we’ve been able to have this support from CPRIT.”

Tex Med. 2019;115(10):18-23

October 2019 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page