Suicide announces itself in many ways. For Austin psychiatrist Thomas Kim, MD, word came recently in the form of a blunt phone call from a patient.

The man had been working 100 hours a week to impress his boss, and it was predictably harming his mental health.

Dr. Kim recalled the patient’s words: “I don’t think I’m going to make it.” Dr. Kim shared the story while taking part in the latest panel discussion in the Texas Medical Association and Texas Public Health Coalition’s (TPHC’s) Distinguished Speaker Series: “Behavioral Health & Suicide Prevention: What You Can Do,” held in November. Dr. Kim reassured the man, and together they came up with a plan to help him through the crisis. Without that help, the situation “would most decidedly have taken a dark turn,” Dr. Kim said.

While that’s a happy ending to this incident, most people don’t have a psychiatrist or counselor they can call on right away, he says. Texas ranked last out of all 50 states and the District of Columbia for overall access to mental health care, according to the 2022 State of Mental Health in America report (tma.tips/2022MentalHealthAccess).

More importantly, much of the U.S. health care system is not geared to identify patients at risk of suicide or provide services when they’re identified.

“If we don’t start looking upstream, if we don’t start avoiding crises before they come, we will never have enough resources,” Dr. Kim said. “We will never have enough to take care of this issue, and it will only get worse.”

One of the most effective ways physician experts point up to identify people who may be at risk for suicide: screen them for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) – preventable, potentially traumatic events that occur before age 18 such as neglect, divorce, and witnessing or experiencing violence.

The connection between the number of ACEs a person experiences and suicide is strong, says a report on suicide among young people published in the Oct. 14, 2022, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (tma.tips/CDCSuicide2022).

Many people assume that the root causes of suicidal thoughts and actions are biological, Dr. Kim says. But ACEs often play an important role.

Experiencing the severe, prolonged “toxic” stress caused by ACEs in childhood has long been known to result in unhealthy choices such as smoking, drinking, or overeating. But research shows that toxic stress changes brain development. This can make people more susceptible to chronic and infectious diseases as well as suicide.

Research also shows the risk of suicide rises sharply along with the number of ACEs, according to the CDC report. Children reporting four or more ACEs were about 25 times more likely to report poor current mental health and suicide attempts compared with those without ACEs. Exposure to specific types of ACEs – like emotional or physical abuse – also were associated with a higher prevalence of poor mental health and suicidal behaviors.

Discussing such experiences can promote a healthier conversation, Dr. Kim says. “[Addressing ACEs] tends to not label somebody as being defective in some shape or form,” and focuses instead on “the complexities that swirl around all of us,” Dr. Kim said.

Physicians may have ample opportunity to intervene before suicide occurs, according to statistics shared by panel member Kimberly Roaten, PhD. She is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UT Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Health & Hospital System, and a senior fellow for suicide prevention at the Texas-based Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute.

Nearly all people who die by suicide have a health care encounter in the year before death, she said. Nearly half of those patients have that interaction within four weeks of death, and 30% within seven days. Moreover, most of these encounters are with physicians in primary care or emergency medicine.

Dr. Roaten points to plenty of tools physicians can use to identify those who are most at risk for suicide, like the free questionnaire provided by the National Institutes of Health (tma.tips/ASQScreeningTool). And if a hospital or clinic has not done much work on preventing suicide, there are plenty of others who have and can serve as models.

“We don’t need to reinvent the wheel for this,” she said. “We know what works. We need to be ahead of the game in preventing suicide, and we have the evidence base that tells us how to do that. If another hospital is doing the work that needs to be done in your system, do what they do. You don’t have to start from scratch.”

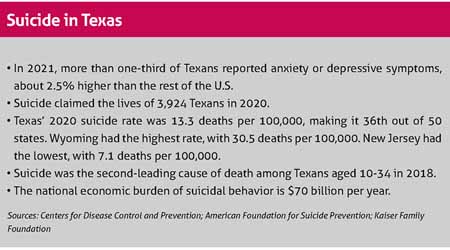

Suicide is a particular concern among teenagers because it is the second-leading cause of death among young people in the U.S., says Celia Neavel, MD, medical director for the Center for Adolescent Health at People’s Community Clinic in Austin. (See “Suicide in Texas,” above.)

Intervening in the primary care setting can save lives by identifying patients who need help and save money by avoiding costly hospital stays, she says. Her clinic uses a collaborative care model that screens patients aged 12 and up and – among other services – provides psychology interns supported by consulting psychiatrists for more complex cases. The clinic also uses community resources to help address the needs of patients and their families, such as food and clothing.

“We provide place-based, effective, patient-centered care,” Dr. Neavel said. But she added: “Even with all that, I still don’t have enough.”

The panel used a composite 16-year-old named “Sam” to give examples of some of the typical problems tied to ACEs and suicide for teenagers. For instance, the fictional Sam struggled with his parents’ recent separation and family financial problems. The panel also described how rapid intervention by a team of medical professionals helped keep him from further harm.

“We’re not talking about psychiatrists or psychologists who just happen to have an office in the same hallway as the internist,” Dr. Roaten said. “We’re talking about behavioral health specialists who actively collaborate with primary care physicians.”

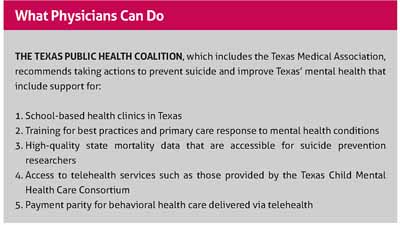

Texas physicians also can improve health care for young people by advocating for more school-based health clinics, which are medical clinics in or near schools, Dr. Neavel says (tma.tips/SchoolClinics). These clinics are usually staffed following a collaborative care model with an interdisciplinary team of physicians and other health care professionals – including psychiatric consultants.

The trauma from adverse childhood experiences has been made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the October CDC report. About 73.1% of U.S. high school students reported at least one ACE during the pandemic, while 53.2% reported two, 12% reported three, and 7.8% reported four or more, the study says.

“These students were more likely [than those not reporting ACEs] to report poor mental health and suicidal behavior,” the study’s authors wrote.

Many physicians who worked with young people during the pandemic have personal experience that matches the report’s conclusions, Jeff Hutchinson, MD, an adolescent medicine specialist at People’s Community Clinic, told Texas Medicine.

“A lot of the patients we have taken care of come from either neglect or abuse, or witness trauma all the time,” he said. “And our population’s rate of suicide, anxiety, and depression seems to have really increased since the pandemic.”

Texas already has made progress in improving behavioral health care with the creation of the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium, which provides a range of services for both children and women of child-bearing age. (See “PeriPAN Provides a New Tool for Physicians,” November 2022 Texas Medicine, pages 38-40, www.texmed.org/NewPeriPAN.)

But since access to mental health professionals remains a problem, one of TMA’s top priorities for the 2023 legislative session is to improve behavioral health care for women and children. (See “Priority: Medicaid Coverage for Women and Children,” page 18.)

Even when improved resources become available, primary care physicians will remain on the front line in identifying and treating people at risk of suicide, says Lubbock pediatrician Celeste Caballero, MD, who testified for TMA at a hearing of the Senate Special Committee to Protect All Texans – formed in response to the 2022 Uvalde school shooting. She called for bolstering the state’s mental health care system and enhancing family-child interventions.

Physicians should never look at a person with multiple ACEs – or the types of ACEs tied to suicide risk – as a lost cause, Dr. Caballero says. She worked in a federally qualified health center in San Angelo for eight years, taking care of mostly low-income and immigrant children. The harsh problems many children face frequently are buffered or softened by other factors, such as having a loving family member or friend.

“I saw a lot of examples of adverse childhood experiences affecting children that really changed the trajectory of their lives,” she said. “I saw instances where children had buffering effects from the ACEs and I saw good outcomes. And I saw very poor outcomes because there were no bufferings.”

Data like the recent CDC report can help physicians examine individual patients with an eye toward recognizing who might be suicidal, Dr. Hutchinson says. But physicians also need to use that data to think bigger by creating clinic-wide policies – when needed – that provide comprehensive screening and mental health services.

“It should change what you do as policy, not [just] what you do for individuals,” he said.