The physicians who worked for Austin-based Hospital Internists of Texas in 2018 knew they were in a financial mismatch when they filed suit against the company that St. David’s HealthCare uses to staff its chain of hospitals.

Hospital Internists of Texas, along with Hospital Internists of Austin and Texas APN, alleged that staffing companies Quantum Plus and Lonestar Hospital Medical Associates violated Texas’ corporate practice of medicine laws by trying to exercise improper control over patient care. Quantum Plus and Lonestar are an indirect subsidiary and an affiliate, respectively, of Team Health Holdings, Inc., which is owned by Blackstone Group.

To Hospital Internists of Texas, this meant the practice’s 85 physicians and 35 advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) were essentially pitted against a multibillion-dollar company. Those felt like long odds, says Ellis Doan, MD, the chief medical officer for the practice.

While the suit dragged on for four and a half years – in part because COVID-19 shut down courts for a while – the outcome at the trial court level has been a win for the hospitalists and nurses, to whom a Travis County district court jury awarded more than $10.2 million total, based in significant part on the staffing companies’ breach of the services agreement with Hospital Internists of Austin, including Quantum’s failure to comply with state law.

The case is highly unusual, in part, because physicians tend to be risk-averse when it comes to this type of litigation, says Austin health care attorney Amanda Hill, who consults with the Texas Medical Association and is not involved in the case.

The case has cost the physicians working for Hospital Internists of Texas a lot, says Dieter Martin, MD, a former president of the practice. The organization has shrunk to 29 physicians and 25 APRNs, according to its website. Each of them has had to take pay cuts to help pay for the suit.

But Dr. Martin’s verdict on the suit? Totally worth it.

“My professional satisfaction has just skyrocketed in the last five years,” he said.

Hospital Internists of Texas physicians no longer have a comfortable contract with a hospital system, as they did before, he says. Instead, they’ve worked largely through referrals from other physicians and medical groups, and that has given them the freedom to make medical calls the way they see them.

“When I’m in the room with the patient, it’s just me and the patient. We can figure out what’s the best thing for them, and that’s what I became a doctor to do,” Dr. Martin said.

Texas Medicine reached out to TeamHealth for comment, but the company did not respond by the time this story went to press. St. David’s, which is not a defendant in the suit, declined an interview but provided the following emailed statement from Ken Mitchell, MD, its chief medical officer:

“The basis of the lawsuit by Hospital Internists of Texas (HIT) against TeamHealth was, in part, that TeamHealth and St. David’s HealthCare were holding HIT accountable for improved performance. ... While we respect the jury’s verdict, we stand by the improvements that resulted from these efforts and disagree that those efforts were contrary to restrictions on the corporate practice of medicine.”

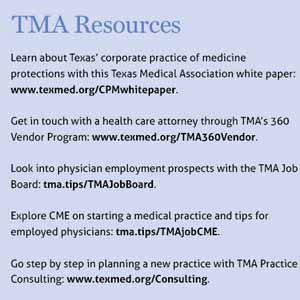

In theory, Texas physicians have plenty of legal protection in corporate practice of medicine cases. Since 1956, Texas has had some of the strictest prohibitions in the country. Those laws and legal precedents, supported by TMA, are designed to keep lay people and organizations from interfering in a physician’s medical judgment, especially for financial reasons. (See “TMA Resources,” below.)

Texas corporate practice laws, among other things, bar nonphysicians from employing physicians – though there are exceptions. For instance, in 2011 Texas amended its law to allow critical access hospitals, sole community hospitals, and hospitals that serve populations of 50,000 or fewer to directly employ physicians, largely to improve access to care in underserved areas.

While Hospital Internists of Texas physicians are in private practice, an increasing number of U.S. physicians are not, and that has helped make corporate practice concerns more common, Ms. Hill says. Between 2019 and 2022, the percentage of U.S. physicians who were hospital- or corporate-employed rose by 19% to 74%, according to the Physicians Advocacy Institute.

Ms. Hill says physicians regularly complain to her about being forced to sacrifice their medical judgment. “I just talked to a doctor today who was told [by a private equity firm], ‘You’ve got to cut costs. This is too expensive. … This is how you can lower expenses,’” she said.

Corporate practice of medicine conflicts can arise with different types of entities, including hospitals and insurance companies. Many contracts push physicians toward arbitration, in which an arbitrator or a panel of arbitrators privately hears the case and makes a decision that generally cannot be appealed. On request of a party, a court must confirm an arbitration award, except in very limited circumstances where the court may invalidate, modify, or correct the award. That makes it difficult to tell exactly how widespread corporate practice issues are because the disputes are rarely heard in court.

Physicians who knowingly give in to corporate pressures at the expense of patient care can face investigation and punishment by the Texas Medical Board.

The lawsuits that result from those cases usually focus on the physician, not the administrators or entity ordering the physician to act, Dr. Doan says.

Employed physicians can best avoid corporate practice of medicine conflicts by choosing their workplace well, Ms. Hill says. Before joining, look at its financial history, how many times it’s merged or been sold, and who ultimately owns it.

Physicians who find themselves being pressured to sacrifice their medical judgment should follow good negotiation techniques and find a point of leverage, she says. Research the entity’s finances to show the benefit of not pursuing short-term profits over the needs of patients.

“If you have zero leverage, nobody will listen to you,” she said. “You have to work with the [corporate entity] and explain that what you’re doing is not only in the best interest of the patient but saves them money.”

The pressure on physicians to undermine corporate practice of medicine laws is often intense, and saying no to the nonphysicians applying that pressure can be difficult and involve risks, Dr. Doan says.

“But the return on doing what’s right is the most important thing,” he said.