Related Content

What the End of the COVID PHE Means for Vaccines, Testing, Treatment

What the End of the COVID PHE Means for Telehealth

*Editor's note: After nearly three years and 11 extensions, the Biden administration on Jan. 30 announced the COVID-19 public health emergency would end May 11.

Prepandemic, Round Rock pediatrician Maria Scranton, MD, says she often saw patients whose Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) coverage had lapsed.

Their parents might have become ineligible because of a change in income, or they may have forgotten to reenroll. Other families might have moved, meaning their usual reminder didn’t reach them. Whatever the reason, such lapses could make necessary care and prescriptions unaffordable.

That changed with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act temporarily increased federal Medicaid matching dollars by 6.2% for states that agreed to maintain Medicaid coverage for anyone enrolled in the program from March 2020 through the end of the public health emergency (PHE).

That included Texas, and that translated to continuous Medicaid coverage for more than 2.5 million Texans, predominantly postpartum women and children, according to a Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) estimate.

But after nearly three years and 11 extensions, the PHE is poised to expire this spring, and with it, that extended coverage. “It is definitely very concerning,” said Dr. Scranton, who chairs the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured.

State Medicaid officials do have a plan for this unwinding. But it means redetermining patients’ Medicaid eligibility once the PHE ends – a process Dr. Scranton described as “so, so complicated.”

Disenrollments would start as soon as the first month after the PHE ends. Although many Texans will remain eligible for the program, some will be disenrolled either because they no longer meet the eligibility criteria or because of administrative churning. The latter means they could lose coverage, despite remaining eligible, because of difficulties navigating the renewal process, address changes, and other bureaucratic barriers. In either case, patients stand to lose coverage in the middle of treatment, and many of them will not qualify for other forms of coverage, leaving them uninsured.

TMA and HHSC officials urge physicians to prepare their patients for this looming coverage cliff. Although physicians agree that this outreach is critical, some say they don’t have the bandwidth to take on additional responsibilities given ongoing pandemic pressures. Others, including Dr. Scranton, worry the sheer volume of redeterminations will overwhelm an already strained eligibility system.

Fortunately, the end of the PHE coincides with some recent policy developments, including increased federal funding for navigators – community organizations that connect eligible consumers to federal marketplace health plans – and extended subsidies for the same plans.* TMA experts say these changes could help some Texans who lose Medicaid coverage enroll in a different plan.

*After this story went to press, President Joe Biden on Dec. 29, 2022, signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, a $1.7 trillion spending package that makes permanent an option for states to provide 12 months of continuous Medicaid coverage to children and postpartum women, among other provisions.

But they also warn that many of Texas’ lowest income workers will lose coverage, and the transition will be chaotic for physicians and patients alike.

The role of physicians

The state’s three-phase plan relies heavily on physicians – along with other health care professionals, Medicaid health plans, and community organizations – to raise awareness among Medicaid patients about the unwinding process. But TMA and member physicians have raised concerns about feasibility.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has issued guidance, giving states 12 months after the PHE ends to initiate the eligibility process, plus an additional two months to complete any pending redeterminations.

In accordance with this guidance, HHSC developed a plan to unwind continuous coverage and to redetermine eligibility for more than 2.5 million Medicaid patients in just eight months. In a September presentation, HHSC officials said redeterminations will be divided across three cohorts:

- The first and largest group will be the approximately 1.4 million Texas Medicaid patients who are most likely to be deemed ineligible for coverage or to transition to CHIP;

- The second will encompass the approximately 500,000 individuals who are likely to switch to a different Medicaid eligibility group; and

- The final cohort will consist of the approximately 640,000 million individuals, primarily children, who are most likely to remain eligible.

TMA and nine other Texas organizations dedicated to improving health care access have questioned HHSC’s abbreviated timeline, given the scope of the transition.

“According to a recent survey of state Medicaid plans, Texas will be one of only [nine] states attempting to unwind the PHE-related continuous eligibility provision without allowing up to a year,” the signatories wrote in a March 31 letter to HHSC. “Additionally, unwinding too quickly will result in human and financial costs, not only to millions of Texans but also [to] the state’s safety net, already strained by the pandemic.”

TMA is collaborating with the other organizations to prevent such an outcome, including by encouraging HHSC to:

- Leverage data, automation, and flexibility to ease some of the burden on the eligibility system;

- Improve access to its “211” help program by increasing staff to address wait times or by establishing a dedicated line for Medicaid patients to update their contact information; and

- Maximize patient outreach via text to ensure eligible Texans maintain coverage.

Austin oncologist Debra Patt, MD, says patient outreach is especially important given the limited capacity of practices like hers, which have taken on extra work during the pandemic. That includes counseling patients about COVID-19 vaccinations, managing care that patients have let lapse during the pandemic, and dealing with increased mental health needs.

“And that’s in addition to the cancers we’re treating,” she said.

Dr. Scranton says her practice, aided by its in-house marketing department, has been preparing patients’ families since last summer. But she’s heard mixed reactions when she raises the topic during appointments. Some parents are prepared to reenroll when the PHE ends, while others aren’t aware that they’re benefiting from special circumstances.

Dr. Scranton also worries about how her patients’ families will adapt once continuous Medicaid enrollment ends. She says some of her patients enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP for the first time during the pandemic after their parent lost his or her job and became newly eligible for the program. Their families have never experienced Texas Medicaid without continuous enrollment – and aren’t aware of the onerous income checks that normally are required.

Other patients were enrolled in Medicaid before the PHE, but their parents haven’t had to reenroll in the program since March 2020. In 2021, state lawmakers voted to make enrollment simpler, but the changes haven’t been implemented yet because of the pandemic.

“I can’t imagine the impact on people who haven’t had to do renewals for nearly three years getting back into that,” Dr. Scranton said.

HHSC also reports a high rate of returned mail, indicating many patients have moved or are otherwise unreachable, exacerbating these concerns.

Texas' steep coverage cliff

Despite HHSC’s plan and the contributions of physicians in raising awareness, Texas Medicaid patients are at higher risk of losing coverage when the PHE ends than their counterparts in other states.

“Each state administers the Medicaid program a little differently,” Dr. Patt said. “In Texas, there’s a high administrative burden to maintain eligibility.”

Nearly half of the 15 million Medicaid patients across the U.S. could fall into this coverage gap as a result of administrative churning, according to a recent issue brief from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE).

“The risk of administrative churning may be particularly high after the PHE due to the volume of redeterminations states must conduct and the time since Medicaid agencies last communicated with many beneficiaries,” ASPE wrote.

Although the brief doesn’t include state-level estimates, previous analyses indicate Texas Medicaid patients are especially vulnerable.

For instance, a February 2022 report by the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families found children were most likely to lose coverage in states that:

- Have separate CHIP programs;

- Charge premiums for CHIP coverage;

- Don’t provide 12 months of continuous coverage for children in Medicaid; or

- Process less than half of their renewals using existing data sources.

Texas is one of six states that has all these risk factors, according to the report.

Dr. Patt says the unwinding process stands to worsen lapses in coverage.

“Those care delays pose a risk to patients,” she explained.

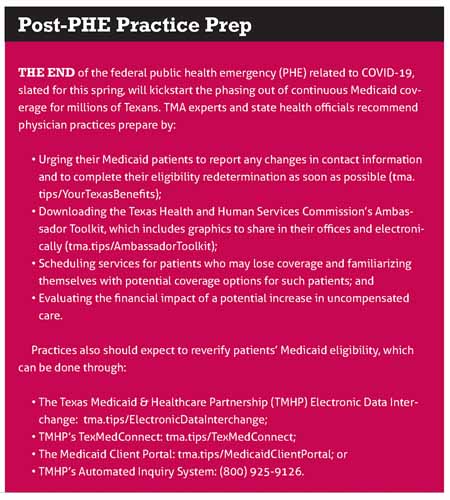

Such lapses also impact physicians, who face a possible uptick in uncompensated care and Medicaid verifications once the PHE ends. (See “Post-PHE Practice Prep,” page 33.)

“It’s a challenging problem, and the administrative burden is great,” Dr. Patt said.

Mitigating factors

Amid these challenges, however, the Biden administration has enacted several policies that could help smooth out the unwinding and help connect Texans who lose Medicaid coverage to other health plans, says Helen Kent Davis, TMA’s associate vice president of governmental affairs.

Last August, the administration announced it would grant $98.9 million to scores of navigator organizations across the U.S., including 10 in Texas, enabling them to retain and recruit staff ahead of the 2023 open enrollment period, which runs through Jan. 15.

This is the largest funding award to date and builds on the 2022 open enrollment period, when the administration granted $80 million in navigator funding and a record-breaking 14.5 million people signed up for coverage, according to HHS.

That same month, President Joe Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act, which extends subsidies for federal marketplace health plans through 2025. The White House estimates these subsidies will save 13 million Americans, on average, $800 per year on premiums. The law builds on the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, which increased federal subsidies for certain health plan premiums.

Ms. Davis says these subsidies could help blunt the impact of the PHE ending – so long as Texans who lose Medicaid coverage while remaining eligible for subsidies get connected to marketplace coverage.

Finally, the administration issued a final rule in mid-September that closes the so-called “family glitch” loophole under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), heeding advocacy by TMA and by the American Medical Association.

Previously, families could be denied subsidies for federal marketplace plans if one member had “affordable” insurance through his or her employer, even if that coverage became unaffordable when extended to the entire family, according to AMA.

Under the new rule, the affordability of employer-sponsored coverage for family members is based on the employee’s cost of covering everyone, not just him- or herself.

Although critical for some, these policies aren’t a cure-all. Ms. Davis says many of the poorest Texas parents and workers won’t benefit from subsidies. The ACA precluded people with incomes below 100% of the poverty line from enrolling in federal marketplace coverage based on the assumption that all states would extend their Medicaid programs’ coverage to them. However, Texas is one of only 11 states that haven’t done so.

As a result, Texas’ uninsured rate stands to worsen after the PHE ends. At 20.4%, it’s already the highest among U.S. states and more than twice the national average, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Dr. Scranton says there’s not yet state-level data quantifying the potential health benefits of continuous Medicaid coverage, in part because the pandemic disrupted how patients accessed care, and because it takes time to collect such information. (Texas children enrolled in CHIP already receive 12 months of continuous coverage. Thirty-two other states provide continuous coverage for all children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP.)

Still, Dr. Scranton sympathizes with her patients who will undergo eligibility redeterminations, which stand to unwind more than just ongoing health coverage.

If continuous coverage were to stay in place, “we know that we would see benefits” in continuity of care, she said.