Harlingen family physician Sheila Magoon, MD, suspected loneliness was a driving force behind poor outcomes among her older adult patients.

So, through her accountable care organization (ACO), Buena Vida y Salud, she developed a senior buddy pilot program in 2017. One patient loved the program so much that she volunteered to serve as a buddy herself.

“It helped her blossom and return to some of the vitality she used to have,” said Dr. Magoon, who serves on the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured.

During patient visits at ARC Senior Care, Pflugerville geriatrician Gowrishankar Gnanasekaran, MD, follows what he called “the 90-second rule” at the clinic, which is focused on coordinated primary care for eligible Medicare and Medicare Advantage patients aged 55 and older.

“Any time I see a patient, I first let them speak,” he said. For the first 90 seconds, “I do not interfere or interrupt when they’re talking.”

Doing so ensures he learns of the patient’s concerns and priorities – for example, getting well enough to travel to a loved one’s wedding – before categorizing them into certain medical diagnoses.

Dallas geriatrician Deborah Freeland, MD, similarly values patients’ input in UT Southwestern Medical Center’s home-based primary care practice. Seeing patients at home eases certain access challenges, like transportation, and gives her insight into the nonmedical drivers of health at play. (See “Drivers Ed,” page 32.)

“This allows for better interventions, as the social issues are more easily understood and recognized when seeing a patient in their home,” she told Texas Medicine.

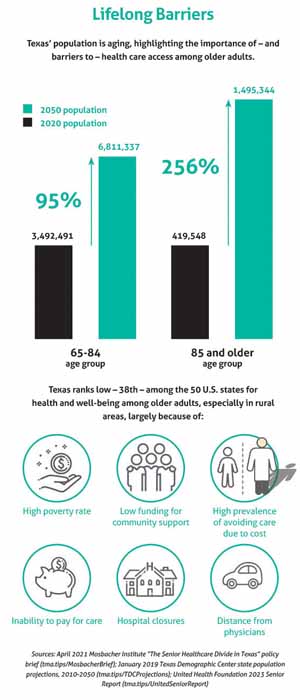

Texas’ population is aging, highlighting the importance of health care access among older adults. The Texas Demographic Center projects the state’s fastest growing age groups are those 85 and older and those aged 65 to 84. (See “Lifelong Barriers,” page 29.)

But Texas ranks low, 38th, among the 50 U.S. states for the health and well-being of these demographics. Older adults in rural Texas are particularly vulnerable, given physician workforce shortages and other obstacles. (See “Coming Up Short,” page 12.)

Drs. Magoon, Gnanasekaran, and Freeland agree that many of their older adult patients are in dire need of high-quality, coordinated care that bridges complex systems, various clinicians, and concurrent chronic conditions. Each also is passionate about innovating new and effective ways of meeting this need.

“There’s so much choppiness and fragmentation,” Dr. Gnanasekaran said. “The more coordinated the care is, the better outcomes are, and the better understanding the patient gets about his health.”

In search of a solution for emergency department (ED) overuse among Buena Vida y Salud’s patients, Dr. Magoon theorized a treatment for loneliness. The resulting senior buddy program has had anecdotal success and slow growth.

Dr. Magoon first became interested in loneliness after reading The Broken Heart: The Medical Consequences of Loneliness by James Lynch and, later, discussing with one of her ACO’s member physicians the challenge of “frequent flier” patients who visited the ED several times each year.

“No one’s going to tell you, ‘I’m going because I’m lonely,’” she said.

But Dr. Magoon trusted her instincts and partnered with local faith-based organizations and her own recently retired pastor to establish pairs of senior buddy program volunteers. Initially working with just one primary care physician, the program accepted referrals of high-risk patients and coordinated bimonthly or weekly in-person visits, during which volunteers conducted a basic assessment and socialized with the patient before following up with the referring physician.

Over the next few years, the program expanded to additional primary care physicians and trained the ACO’s staff to assist with scheduling and other logistical tasks. When participating physicians reported difficulty identifying patients for referral and talking to them about loneliness, the program developed a screening tool and trained practices on the healing value of such relationships.

“There’s a discomfort with talking about loneliness,” Dr. Magoon said. “Adjusting somebody’s diabetic medication ... is very different.”

Today, the program typically enrolls 10 patients at a time. Despite its small size, Dr. Magoon touts its impact in reducing the number of frequent fliers’ annual ED visits and in terms of positive feedback – from an enrollee making the fraught transition to a skilled nursing facility and from the caregiver spouse of a patient with dementia, for instance.

“Even if it never gets out of pilot phase, we’re still going to continue to push it because it’s so powerful on the individual person level,” she said. “Because it is a difficult topic, it’s going to take a long time to grow it on the community level.”

Hundreds of miles away in central Texas, Dr. Gnanasekaran also works to improve outcomes among his older patients through relationship building and by offering comprehensive care tailored to their individual needs.

Dr. G, as he is known to his patients, recently relocated from Cleveland, Ohio, to care for his own aging parents and to help build ARC Senior Care.

The geriatric clinic offers an alternative to the norm. Where many primary care physicians have a monthslong waiting list for new patients and see existing patients every three to six months, Dr. G sees his Medicare and Medicare Advantage patients as often as is necessary to manage their multiple chronic conditions and to prevent unnecessary ED visits and hospitalizations. He also coordinates their care among specialists and health professionals.

As each doctor takes on a portion of the patient’s care, “geriatrics connects all the dots,” he said.

Demand for this type of care is growing, and ARC Senior Care is working to expand its staff.

“It has been pretty steep and rapid growth since our [April 2023] inception,” he said.

Critically, Dr. G adds, Medicare pays physicians for providing such coordinated care. The federal program has a stated goal to transition all patients from fee-for-service arrangements, such as traditional Medicare, to value-based models, like the Medicare Shared Savings Program, ACO Reach, and Medicare Advantage, by 2030. For patients enrolled in Medicare Advantage, the program pays private plans a fixed monthly amount based on the patient’s risk score, incentivizing high-quality, cost-effective care. (See “Medicare Advantage – and Disadvantage,” March 2024 Texas Medicine, pages 30-35.)

“Geriatrics is all about high-quality care, and, as physicians, we all want our patients to get high-quality care,” he said.

Similarly, Dr. Freeland was drawn to primary care and, specifically, geriatric medicine because she wanted to be an advocate for her patients.

“I enjoy being the quarterback for my patients and getting to be present and support them through elderhood and even at end of life,” she told Texas Medicine.

While in college, Dr. Freeland worked as a certified nurse assistant (CNA) at a nursing home. The experience sparked her interest in geriatric medicine.

“I noticed there was the possibility for vulnerability and risks of lost dignity, and I felt that I could prevent some of that as a CNA and wanted to learn more and become a physician so I could be better equipped to help older adults as they age.”

After completing her residency in internal medicine, she “realized that geriatricians are experts in understanding the health system and work to address older adults’ needs through different models of care and reduce risks that come from transitioning from different settings of care.”

Today, Dr. Freeland relishes the complexity of the home-based primary care practice’s patient population.

“I am often caring for people with 10-plus chronic illnesses on a long list of medications. We ... use a holistic approach, applying our medical knowledge while balancing what matters most with their function and quality of life.”

She also works to address nonmedical drivers of health that may impede patients’ access to care, such as the need for transportation assistance and the increasingly complex health care system.

In addition to caring for patients at home, she helps circumvent these barriers by working with community organizations that provide additional resources and by advocating for local and state policies that support older adults.

“We are all aging,” Dr. Freeland told Texas Medicine. “It is crucial that everyone advocates for older adults as it will help our whole society.”