Sugar Land internist Cynthia Peacock, MD, treats Medicaid children and young adults who often rely on a steady regimen of medications to treat chronic illnesses or disabilities.

But lately, she’s been forced to alter long-standing treatment plans to accommodate what she describes as “sudden and unannounced” changes to the state’s preferred drug list (PDL) – a predetermined list of medications Medicaid generally covers without the need for prior authorization.

A laundry list of program complexities burdens Dr. Peacock and her staff with last-minute preapprovals and even denials. As they work with Texas’ Vendor Drug Program (VDP) representatives and patients’ pharmacies to correct those issues and find affordable yet effective medication, Dr. Peacock’s patients go without.

“This program is like a revolving door,” the member of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured said. “They change it back to generic, and then they change it back to another brand name, and it goes on and on and on. We never know if we’ll be able to prescribe nonpreferred drugs or how long it will take for patients to get those drugs. It forces us to scramble to adjust treatment.”

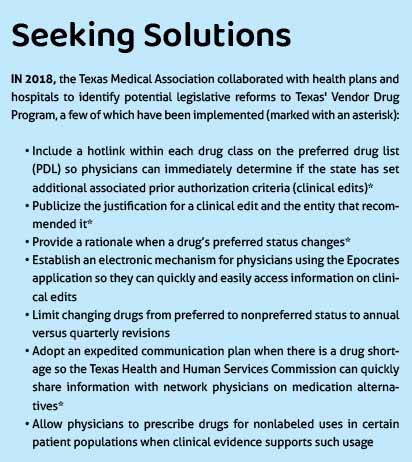

These and other intransigent problems prompted TMA in 2018 to call for an administrative overhaul of the VDP, which provides statewide access to covered outpatient drugs for patients enrolled in Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and other state health care programs. (See “Seeking Solutions,” page 34.)

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC), which oversees the program, has since adopted some of TMA’s recommended reforms, and a new TMA-backed Texas law holds prospects for further improvement.

But because of the ongoing administrative complexity of the program, and its implications for patient care, TMA continues to advocate for change.

“When the formulary works, it works. But it’s taken years for issues to be addressed, and it may take even more years to fix what we have now,” Dr. Peacock said. When patients are left waiting on treatment, “I’m just not sure we have [that kind of] time.”

HHSC Chief Medical Director Ryan Van Ramshorst, MD, acknowledges that rising drug costs and what he calls a “complex” drug rebate system, among other factors, do contribute to program confusion. “We know this is an ongoing issue that physicians bring up.”

To provide more upstream knowledge of the program, he says HHSC has taken steps to upgrade its vendor drug website with hyperlinks to information on prior authorization, a more robust formulary search tool, and more options for tailored searches. The agency also regularly works with stakeholders like TMA, and recent legislative changes could add to program stability, he adds.

“The biggest improvements we’ve made involve the accessibility of the drug program … and we hope these changes help aid physicians on which medications are going to require prior authorization or if a medication is preferred or not preferred,” Dr. Van Ramshorst said.

Unique complications

Under federal law, the Medicaid formulary includes most drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) if manufacturers provide a federal rebate, a provision meant to ensure Medicaid receives the best price.

At the state level, a Drug Utilization Review Board comprising physicians, pharmacists, a consumer, and a managed care organization (MCO) medical director advises HHSC on the category in which to place each drug based on a review of that medication’s efficacy, safety, and cost. States must then make these drugs available to Medicaid patients based on what the PDL identifies as “preferred” or “nonpreferred” drugs within each specified drug class.

But physicians are usually in the dark about modifications to that list, says Dr. Peacock.

“It’s not like they send us a notice,” she said. “We only find out about changes to the drug list when families try to fill prescriptions, and their pharmacies call us to say … that medication [isn’t covered]. The communication isn’t there.”

Further complicating the program, federal rules allow states to pursue supplemental rebates from drug manufacturers to curtail rising prescription drug costs. Medications without a supplemental rebate, however, generally cannot be considered preferred.

This process results in brand name drugs being preferred despite a generic drug’s availability, an ongoing problem that Dr. Van Ramshorst admits is complicated.

“Generally speaking, generic medications tend to cost less than brand name medications. However, in Medicaid, we factor in rebates that make the system more complex than just listing generic or brand name,” he explained.

Dr. Peacock called the rebate system “counterproductive, given that the entire point of this system is to make medication more affordable for these patients. And yet, we’re forced to prescribe these brand name prescriptions, which drives costs up.”

“In essence, drug companies give money to the state if their medication is placed on the formulary,” she said. “I’m afraid of what that means for Medicaid patients who need medications [that end up getting] replaced on the formulary.”

Among other payers, generic drugs – which FDA requires to be the same as a brand “in dosage, safety, effectiveness, strength, stability, and quality” – are almost always preferred. Many value-based payment programs, for instance, reward physicians for higher generic drug prescribing, says Helen Kent Davis, TMA’s associate vice president of governmental affairs.

Other complications unique to the Vendor Drug Program that are not typical among commercial and Medicare drug plans include:

- Requiring pharmacists to dispense only drugs for which the state has a rebate for a specific national drug code (NDC);

- Long waits to add FDA-approved drugs to the formulary; and

- Less flexibility to amend the PDL to allow nonpreferred drugs to be prescribed without prior authorization when a preferred drug is not available.

Often, preferred drugs also are subject to additional clinical review, meaning prior authorization might be required even if those medications are on the PDL.

While there are often valid, evidence-based reasons for these reviews (such as preventing adverse drug reactions), it’s difficult for physicians to quickly and easily determine where prior authorization might apply, fueling confusion, says Austin pediatrician Maria Scranton, MD. The VDP website does provide this information in PDF format, but it is not easily imported into most electronic health records. HHSC recommends physicians use the Epocrates application to review the Medicaid formulary.

She recalls the shock of needing preapproval for an albuterol prescription despite the medication being preferred – and not knowing where to look to find alternatives.

“By the time patients come to see me, they’ve been needing their medication for a few days. People cannot wait,” said Dr. Scranton, chair of TMA’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured. “If we need prior authorization for a basic asthma inhaler, imagine the hoops we have to jump through for more complex patient needs.”

Additionally, VDP administration has been split between the state and MCOs. Although HHSC develops and maintains the statewide formulary, PDL, and prior authorization policies, the managed care organizations carry them out and are the face of the program.

“As an advocate and physician focused on trying to keep health care costs down when I can, it hurts coordinating all of the puzzle pieces – formulary, NDC, MCOs, and pharmacies – to address the systemic issues that I’m not sure will be addressed in time to care for my patients,” Dr. Scranton said.

Legislative changes ahead

Medicaid managed care plans were set to assume oversight and responsibility for the Medicaid outpatient prescription drug benefit in September, after which each MCO would have been able to develop its own drug lists and policies. However, lawmakers enacted House Bill 1283 by Rep. Tom Oliverson, MD (R-Cypress), which repealed the shift in favor of keeping the rebate structure as more financially beneficial to the state.

A 2021 report by the State of Texas Vendor Drug Program Formulary Control found that shifting control of the VDP from the state to MCOs would cost $15 million to $18 million more per year from 2022 to 2025.

While physicians support state efforts to minimize Medicaid costs, Dr. Scranton says this type of analysis doesn’t factor in any program costs to patients and their doctors.

TMA remained neutral on the issue but supported legislation to resolve as many hassles as possible within the current framework. That legislation, House Bill 3286 by Rep. Stephanie Klick (R-Fort Worth), took effect Sept. 1 and, once implemented, aims to simplify the VDP by:

• Including all drugs and national drug codes made available under the federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program if a request for the drug’s inclusion in the program has been submitted to the commission;

• Allowing certain exceptions to the PDL so physicians can prescribe nonpreferred drugs more efficiently, for example if the preferred drug will cause an adverse reaction, has shown to be ineffective, or is unavailable; or if switching a stable patient from a nonpreferred to a preferred drug risks complications; and

• Adding two more Medicaid MCO representatives, who must be either physicians or pharmacists, to the Drug Utilization Review Board to promote better coordination of policy and processes between the VDP and the MCOs.

Dr. Scranton praised the Texas Legislature but stressed that to make the program more accessible for physicians and patients, there’s still work to be done.

“There’ve still been times I’ve called patients to see how they’re doing on the medication to find they never started taking it because it wasn’t covered,” she said. “The Vendor Drug Program has a long way to go.”

HHSC’s Dr. Van Ramshorst anticipates HB 1283 will contribute to program stability by allowing physicians to “refer to one, same statewide preferred drug list for all patients.”

He also encourages physicians to share their feedback by participating in the variety of advisory committees the agency oversees like the State Medicaid Managed Care Advisory Committee and the Drug Utilization Review Board.

“We are always looking for new members. We encourage any interested stakeholder or physician to apply for those positions – or to work with organizations like TMA, which we look to for physician input.”

Some of the recent changes may be “a good start,” Dr. Peacock said. But physicians and patients are still “held hostage to this formulary. Until big changes are made, I’ll do my best to ensure people know what doesn’t work about this program – and how those issues affect our patients.”