In 2002, David Cantu, MD, was the only Spanish-speaking physician in the Fredericksburg area delivering babies.

But like many Texas physicians at that time, the family physician’s medical liability insurance premiums soared so high that he had to stop all obstetric services.

“Even though I was doing five or six deliveries per week, it was just barely making the overhead for the insurance – or less,” he said.

Some of Dr. Cantu’s patients could turn elsewhere. But many couldn’t because of the language barrier or because they had Medicaid coverage, and no other local physician could afford to take them.

“They had to figure it out by driving to San Antonio to do their delivery,” a 70-mile car trip at least, he said.

Twenty years ago, physicians all over the state faced the same challenges, especially those who provided high-risk services like obstetrics, neurosurgery, emergency medicine, or orthopedics.

Medical liability insurance rates rose so high, so fast because except in wrongful death lawsuits, Texas in those days had no cap on noneconomic damages in medical negligence cases, such as pain and suffering or loss of companionship, says Donald P. “Rocky” Wilcox, then the Texas Medical Association’s general counsel. Texas court decisions had declared earlier reforms passed in 1975 and 1977 unconstitutional.

Without a cap, Texas physicians faced a steady increase in lawsuits – many of them meritless – from trial lawyers and plaintiffs hoping that a sympathetic jury would award a huge verdict. Sometimes, just the threat of a lawsuit was enough to win some money.

“You really were betting the farm if you went to trial and risked a jury verdict for $50 million for [pain and] suffering,” Mr. Wilcox said.

Physicians fed up with their ever-unaffordable insurance rates turned to TMA, which already had a plan in motion to change the medical liability landscape in the 2003 session of the Texas Legislature. This year marks the 20th anniversary of TMA’s successful initiative to cap noneconomic damages, ending many of the legal practices that harassed physicians and soon making Texas one of the best states for physicians to practice in. It also led to enduring aspects of physician activism, such as the creation of TMA’s signature First Tuesdays at the Capitol advocacy event.

“I will always think of this [achievement] as TMA’s finest hour as to the good that we were able to do,” said Houston internist Spencer Berthelsen, MD, chair of TMA’s Council on Legislation in 2003.

Crying for reform

But it hardly seemed that way at the time to physicians like Dr. Cantu who shut down services, or in some cases even left the state. What they saw instead was that from 1991 to 1999, awards for noneconomic factors like pain and suffering grew from 35% of all verdicts against Texas physicians to 65% of total judgments, says Jon Opelt, former executive director of the Texas Alliance for Patient Access (TAPA), a group formed by TMA, the Texas Hospital Association, and other medical organizations to respond to the medical liability crisis.

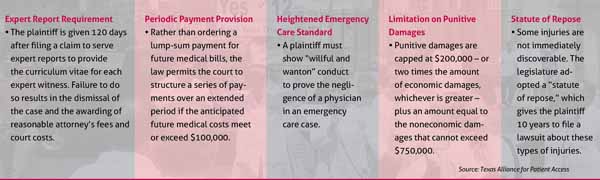

Plaintiffs dropped most medical liability lawsuits before they got to trial because the cases were frivolous, says Norman Chenven, MD, an Austin family physician and Austin Regional Clinic founder who helped campaign for the 2003 reforms. But the psychological impact of getting sued stuck with a physician.

“It ruins the doctor’s life, and it can go on for a year and a half or two years,” he said. “Your entire world has a dark cloud over it worrying about what’s going to happen.”

From 1995 to 2002, claims against Texas physicians occurred at nearly twice the national average, causing liability rates to skyrocket for doctors, hospitals, and nursing homes. Some regions, like the Rio Grande Valley and Gulf Coast, were referred to as “lawsuit war zones” because of the volume of cases filed there, Mr. Opelt says.

As a result, 13 of the state’s 17 liability carriers stopped offering medical liability coverage, he says. About 6,500 out of the state’s roughly 34,000 physicians in direct patient care could only find insurance through the Joint Underwriting Association, the state-run insurance pool of last resort.

Others could get insured through the Texas Medical Liability Trust (TMLT), established in 1979 by legislation TMA supported to provide affordable medical liability coverage, and two other insurers. However, even those carriers had to hike their rates to account for the risk of insuring physicians, Mr. Wilcox says.

“I can remember getting calls from doctors crying because they couldn’t pay their staff and pay their [medical liability] premiums,” he recalled.

A strategy of solidarity

TMA had tried for years to improve medical liability laws in Texas, says Houston plastic surgeon Charles W. Bailey Jr., MD, TMA’s 2003-04 president. TMA leaders like then- Executive Vice President and CEO Lou Goodman met each year with leaders from the trial lawyer industry in an effort to reduce the number of frivolous suits. But those talks led only to minor reforms.

By the early 2000s, two factors began to swing the public argument in favor of physicians.

First, the liability insurance crisis now affected access to patient care as physicians shut down services or left the state, says Edinburg gastroenterologist Carlos Cardenas, MD, who at the time was president of the Hidalgo-Starr County Medical Society and later became TMA president in 2017-18.

Like many of the stories physicians frequently heard at the time, he recounted one about an Edinburg surgeon who saved the life of a woman who had been shot in the spinal cord.

“She walked out of the hospital with a limp, so she turns around and files a lawsuit for malpractice against the surgeon,” Dr. Cardenas said. “Anyone who did a trauma was laying themselves open for medical liability.”

Second, the Texas Legislature became increasingly more favorable to tort reform in medicine, Dr. Berthelsen says. That change in attitude came in part thanks to the efforts by TMA leadership and TEXPAC, TMA’s nonpartisan political action committee, which had spent more than a decade identifying and supporting candidates from both major parties who backed medical liability reform.

TMA based its reform strategy on California’s tort reforms passed in the 1970s, the centerpiece of which was a $250,000 cap on noneconomic damages. But TMA’s plan included other changes as well, such as tightening the rules about who could serve as an expert witness.

TMA officials knew that passing a new law spelling out that cap would not be enough, says Dr. Bailey, who also is an attorney.

“We were having a discussion one time, and [Mr. Wilcox] said, … ‘If we just get a cap with the statute, the [trial lawyers] can come back every year and try to overturn it in the courts. The only way to really lock it in is with a constitutional amendment,’” Dr. Bailey recalled. “When they said that, as a licensed attorney, I thought, ‘What are the chances of that?’ To me that seemed like an overwhelming chore.”

With help from TMA and county medical societies, physicians already had mobilized to conquer that chore. Physicians, nurses, and patients in Edinburg, Corpus Christi, El Paso, and other cities had staged a well-publicized one-day protest march and rally in April 2002. Meanwhile, TMA Alliance members organized the inaugural First Tuesdays at the Capitol events in 2003 to give physicians and their supporters a consistent voice with lawmakers on medical liability reform.

“Prior to tort reform, things reached a fever pitch,” Dr. Cardenas said. “The solidarity that existed in the medical community at the time was reflective of the problem that we had.”

Then-Gov. Rick Perry supported the reform effort as did other leadership at the time, Speaker of the House Tom Craddick and Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst. But marshaling the votes needed among lawmakers to pass a comprehensive reform package was not a sure thing, Mr. Wilcox says.

“Toward the end of the session, [Mr. Goodman] and I were being ping-ponged between the speaker of the house and the lieutenant governor as we were trying to get [an agreed-upon] bill,” he said.

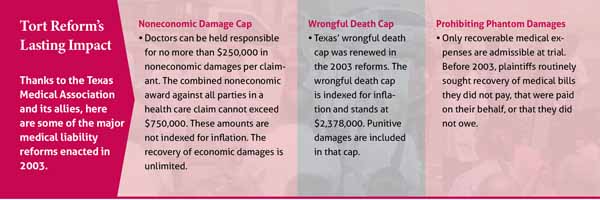

Those negotiations focused on a compromise to the $250,000 cap on noneconomic damages. The solution was a “stacked cap.” Awards against individual physicians could go no higher than $250,000. But if two different types of health care institutions – say, a hospital and a nursing home – were also found liable, the total could rise to $750,000. Neither figure was indexed for inflation, and there was no cap on economic damages.

One more hurdle

House Bill 4, the Medical Malpractice and Tort Reform Act of 2003, went into effect on Sept. 1, 2003, thanks to advocacy by TMA, TAPA, TMLT, and others. Texas lawmakers also passed a constitutional amendment to protect the reforms from legal attacks.

But the amendment had to be approved by Texas voters.

The Sept. 13 vote on the amendment – called Proposition 12 – was hotly contested, says Austin internist Howard Marcus, MD, who chaired the TMLT board and was founding chair of TAPA.

“The night of the election on Proposition 12, some of us got invited to the governor’s mansion to watch the votes come in, and we knew this was going to be a tight race,” he said. “At first, the votes were heavily in our favor, but then they started to narrow down. … At about 2:00 in the morning we got the final totals, and we’d won by [about 2%]. … We’d won by fewer votes than there are [direct patient care] doctors in Texas.”

Almost immediately, physicians like Dr. Cantu began to feel relief.

“The next day after [Proposition 12] passed, I called TMLT insurance and asked, ‘How much would it be now to do obstetrics?’” he said. “It dropped a lot. So, I did some quick math – what would Medicaid bring in versus how much would my insurance be – and I could do it. I, bang, went back into it.”

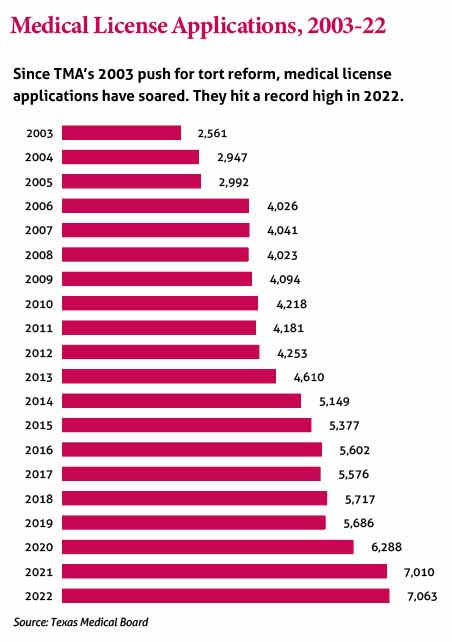

The number of lawsuits also declined. As they did, insurers came back to the state, and Texas became an attractive place for physicians to set up practice.

“It’s been incredibly effective in increasing the supply of doctors throughout Texas,” Dr. Marcus said.

But attacks on the 2003 reforms in the legislature and in the courts have never stopped, Mr. Opelt says.

“The plaintiff lawyers are a very creative bunch,” he said.

The biggest danger to the medical liability reforms is Texas physicians taking them for granted, Dr. Berthelsen says.

“We can never let down our vigilance,” he said. “If we don’t protect it each year, we’ll lose these hard-won protections for our ability to practice medicine.”