At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Emily Briggs, MD, a family physician in New Braunfels, says her small office and local health department were in daily contact by fax and phone to collect data: what kind of tests were performed, how many, and whether the results were positive or negative.

But as COVID rates slowed, so did communication. Even prior to the pandemic, Dr. Briggs received weekly calls for reportable infectious diseases, such as the flu and sexually transmitted infections. Now, she receives no calls at all.

“We’re in a small community that doesn’t have a very highly staffed health department,” Dr. Briggs said. “So, a lot of [reporting] remains with us [physicians and staff], reporting from the office.”

The Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) has more than 90 items listed on its 2023 notifiable conditions list, all of which must be reported within at least a week, if not within a day or immediately.

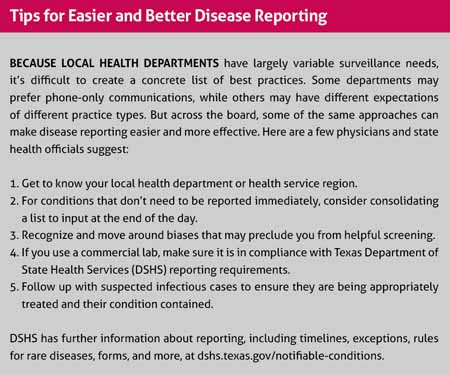

To keep up, Dr. Briggs and her staff devised a system that works for them: They compile a list of reportable diseases to add to throughout the day, and then input the data into individual forms to be submitted at one time at day’s end. This eliminates the hassle of reporting multiple times a day – a particular burden as the reporting process for Dr. Briggs’ local health department still relies on analog means.

“Our EHR (electronic health record) doesn’t really have a workflow for it because the health department requires that it be faxed in,” she said. “There’s not an electronic submission available for us.”

DSHS is well aware of the hassle imposed by fax- and phone-only reporting, according to Imelda Garcia, associate commissioner of the agency’s Laboratory and Infectious Disease Services Division. She says change may be afoot.

“There’s a much better understanding and appreciation for having public health data to help drive things,” Ms. Garcia said. “We [DSHS] need to be better at making it easier for physicians to be able to do it.”

To that end, DSHS has been working with vendors, including EHR vendors, to translate fax reports into electronic ones.

“Then, when we have those physicians’ offices identified, if we know they continue to fax the local health department, we can connect with them and change the message that we’re getting so that it’s not coming in via fax, but it actually will come electronically and can be absorbed into our system,” Ms. Garcia said.

She also praised physicians’ continued efforts to improve processes from the ground up.

“By far, physicians have understood the importance of [public health data],” she said. “They have been able to communicate with their electronic health record companies, so not only do we meet directly with some of the larger EHR vendors in the state, but the physicians themselves have been good about proactively performing some of the changes that needed to be happening.”

Among those changes: growing and maintaining bonds with local health departments, to whom practices directly report disease. Because local health departments are the channel for disease reporting, developing professional rapport with them can smooth a potentially bumpy process.

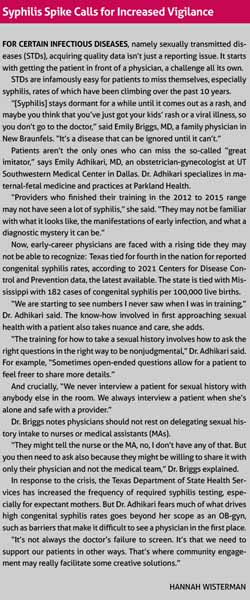

Emily Adhikari, MD, an obstetrician-gynecologist at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, says her institutions’ relationship with local health has been instrumental in managing infectious disease. The maternal-fetal medicine specialist practices at Parkland Health and has seen firsthand how the many-pronged issue of congenital syphilis, for instance, requires a team approach. (See “Syphilis Spike Calls for Increased Vigilance.”)

“The conversations on a weekly basis with our local health department have been really important for us to track our patients,” she said. “[Having] the same face, the same person who knows you, who knows your practice, who knows the patients that you serve, has made it very streamlined.”

And physicians say a working relationship with local health is most beneficial when they have the most accurate data possible to report. That means taking proactive steps in their own practices to watch out for notifiable conditions – even when a case feels unlikely based on a patient’s demographic information.

Much of a physician’s extensive medical training involves learning to recognize patterns, Dr. Briggs says. That’s crucial for diseases with an inherited risk but can also reinforce biases, she cautions. If an infectious disease is more common in certain populations, a physician may unconsciously ignore signs and symptoms of it in other patients.

“In the case of infectious disease, especially in sexually transmitted infectious disease, we really need to be unbiased in our approach to screening,” she said. “We can’t make the assumption that because of gender, because of race, because of ethnicity, that we know whether or not a patient has been exposed to these infectious diseases. It’s best for us to screen unbiasedly in routine, primary care.”

While specialties may vary, both Dr. Briggs and Dr. Adhikari neutralize the role of bias by ordering the same labs for every patient they screen.

Within the office, physicians’ chief disease reporting responsibility, regardless of how a case is reported, is to follow up with the health department and with their patients, Dr. Briggs says.

“The biggest thing is follow-through,” she said. “Don’t assume that something has been handled unless you have specific protocols in place at your office and you’ve watched your staff and done quality assurance to make sure that those protocols are being followed. Because when people fall under the radar and then get missed, that’s when we end up with a much bigger public health problem.”

When it comes to reportable diseases that are discovered outside the physician’s office, such as at an outpatient lab, DSHS’ Ms. Garcia says those entities also work closely with the agency and report promptly. Local public health departments use reported data to devise plans for public and sometimes individual interventions – and their work will circle back into physicians’ care, Dr. Adhikari says.

Learning how to report conditions, and what conditions to report, isn’t a one-and-done endeavor. As was painfully illustrated with the COVID-19 pandemic, new diseases may arise; existing ones may change shape.

To accommodate that, Ms. Garcia says DSHS has built flexibility into its notifiable conditions list by including extensive notes, including instructions to report any unusual expression of disease.

“Anything that’s really strange that you may not know what it is yet, you still should probably pop in to public health and talk about it with us,” Ms. Garcia said. “Even though we didn’t necessarily have COVID maintained specifically on the notifiable conditions list, because it was a novel condition and an unusual expression of disease, we considered it notifiable because we have that catchall.”

The agency also has flexibility to develop testing and tracking protocols.

It takes a larger process to formally change a disease reporting rule. DSHS compares potentially reportable diseases with guidance prepared by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, a nonprofit and professional association. DSHS then surveys local health departments to analyze the need for and feasibility of potential changes. This is where delicate balancing acts unfold between what interventions need to be performed and the resources necessary to do them.

“One of the good examples where we thought we were going to make something notifiable and then at the end we didn’t was making adult influenza deaths reportable,” Ms. Garcia said. “We had asked the local health departments and they thought, yes, it was important to have the data. But in the very end, a lot of the feedback that we got from other folks was just the sheer number [of cases] was going to be too large for them to effectively do anything.

“Every time we add something, there’s not necessarily new money and new staff that comes with it,” she added. “Trying to make sure that we’re not creating an unbearable workload out in the field is important for us to balance.”

Physicians can aid public health interventions by double-checking that their reports have been successfully delivered and by following through on subsequent requirements like reporting completed testing.

But even with limited resources, Ms. Garcia feels physicians are primed to make a difference in public health.

“We really need to leverage the engagement that we have with physicians’ offices, now that they’ve built the tie to public health, now they realize the importance of it,” she said.

“There are very hardworking people all over the state that want to be connected to the providers in their areas. If we can continue to maintain those relationships that we worked [on] so hard and established during COVID, so long as we can stay walking hand in hand with the provider community, the better off we’ll be across everything.”