Rural Texans searching for quality health care often have a long way to go.

In the West Texas city of Big Spring, population 28,000, pediatric patients who cannot get the hospital care they need – and that happens frequently – must drive 100 miles to the hospital in Lubbock, says Big Spring pediatrician Steve Ahmed, MD, president of the Permian Basin County Medical Society.

But even that less-than-ideal solution doesn’t work for many patients, he says.

“The people who have gas money and have resources will drive,” said Dr. Ahmed, also a professor of pediatrics at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) at the Permian Basin in Odessa. “But the poor people who don’t have money … what are they going to do?”

For that reason, Dr. Ahmed – like many rural physicians – has to be a jack-of-all-trades when it comes to medical specialties. For instance, he frequently takes on the role a psychiatrist would normally fill. Such an endeavor can help many patients who are struggling, but it often does not meet physicians’ expectations for care because their lack of expertise becomes compounded by additional nonmedical factors that influence patients’ health.

One of Dr. Ahmed’s 14-year-old patients, for instance, “is using marijuana, and he has anxiety and panic attacks. I cannot get him into any counseling services. The mother is not in the picture. An aunt is taking care of him. I have counseled him as far as I can, but I’m not a professional counselor,” he said. “I’m acting like a psychiatrist here because I have no choice.”

Texas has taken steps to address rural behavioral health care needs by setting up the Child Psychiatry Access Network, which offers pediatricians and family physicians across Texas free telemedicine-based consultation and training on community psychiatry. (See “Making the Right Call,” November 2021 Texas Medicine, pages 26-30, www.texmed.org/CPAN2021.)

But rural physician practices and the hospitals they heavily rely on still face many other problems, says Abilene internist Samantha Goodman, MD, chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Rural Health. Some are the same as those faced by their urban counterparts, including a shortage of nurses and other staff; shrinking payments from Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance; a nation-leading number of uninsured patients; and increased operating costs because of inflation.

“These are not new problems; they just have become more apparent not only with inflation but also during the COVID-19 pandemic,” she said. “A lot of the problems we were already having in terms of infrastructure and staffing have just become exponentially worse – you can’t ignore it anymore.”

Rural areas must confront these obstacles with significant disadvantages compared with urban areas, starting with a shrinking population. Of Texas’ 29 million people, about 3 million live in rural regions, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. That population is in decline, dropping 2.4% between 2010 and 2020, according to a Pew Stateline analysis of U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

Also, rural populations are growing older and poorer in part because residents leave small towns for college or jobs and tend to move to larger cities, Dr. Goodman says. That means rural health care professionals deal more often with Medicare, Medicaid, and uninsured patients.

Many of the problems facing rural health care are decades old, but they have been growing in recent years and demand continued attention from policymakers, Dr. Goodman says. In fact, members of the Texas House of Representatives are studying rural health as part of their interim charges before the legislative session begins in January.

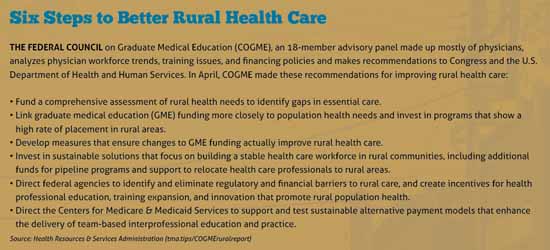

Most solutions to the rural health care crisis boil down to getting more health care professionals into rural areas, either in person or through telemedicine. While some initiatives can be achieved quickly, many will take time and improved funding from both state and federal sources.

Yet, such an investment will almost certainly be cheaper than letting Texas’ rural health care infrastructure decay any further, says John Henderson, president and CEO of the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals (TORCH). For instance, financially struggling rural hospitals frequently scale back or close maternity services to save costs. When they do, local mothers and babies typically suffer severe consequences. (See “Maternity Deserts,” June 2022 Texas Medicine, pages 40-43, www.texmed.org/MaternityDeserts.)

“We tend to think of it in terms of [delivering the baby], but it’s also a problem in prenatal care,” Mr. Henderson said. “You have lower birth weights and higher [newborn intensive care unit] rates and a trend toward mortality and flying babies [to other hospitals for care] that costs the state and the system a great deal both financially and in terms of quality and outcomes,” he said. “We’re much better off bolstering the local care that exists than dealing with these long-term effects.”

Texas leads the nation in rural hospital closures, according to TORCH. Since 2010, 26 have shut their doors either permanently or temporarily in 22 communities.

And when a county loses a hospital, it usually loses any hope of recruiting new physicians to live in that county, says John Gibson, MD, former director of the rural medical education program at the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNTHSC) in Fort Worth.

“There are a lot of doctors who would be willing to go to a community if they had a hospital or if the hospital was more viable,” he said.

Ironically the COVID-19 pandemic gave Texas’ rural hospitals a reprieve as federal money needed to fight the disease helped keep struggling rural hospitals afloat, says Mr. Henderson of TORCH. But that money is drying up, and many rural hospitals will once again face life-or-death financial struggles.

“The last rural hospital closure was in January 2020 in Bowie, Texas, so we’re going on almost two and a half years without a rural hospital closure,” he said. “But I worry that when the public health emergency [declared to fight COVID] ends and you have people rolling off Medicaid [as pandemic-era aid ends], and you lose the benefit of federal stimulus dollars and state-provided staffing that we’re going to have a few rural hospitals that are on the ropes again.”

That’s a huge problem because the death of just one rural hospital reverberates up and down the state’s health care system – and the region’s economy, he says. Hospitals typically are one of the top three employers in any rural county.

“What you see initially is a lack of access to health care” once a rural hospital closes, he said. “As we’ve studied this over time, [we’ve seen] a more profound economic impact, which is that after the hospital closes, the pharmacy closes and the primary care clinic closes and the bank closes and then the grocery store closes and the entire community kind of falls down.”

Low Medicaid payment rates also are one of the factors that hurt rural care.

They have especially factored into the scale-back or even elimination of maternity care, Mr. Henderson says. Medicaid pays for 53% of births statewide, according to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. But it often pays for up to 70% or 80% of births in a rural county, where poverty is likely to be higher than average, he says.

Rural areas have few specialists as is, and many of them don’t accept Medicaid patients because of the inadequate payment, Dr. Ahmed says. That further narrows rural physicians’ limited options to refer patients. It also makes recruiting new physicians a tougher chore.

“It is becoming very difficult to practice medicine in rural Texas,” he said. “First of all, you cannot hire people, and when you can hire people, they go away because they cannot practice in circumstances where they cannot even refer a patient” to a specialist, he said.

Rural hospitals recently welcomed the news that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) renewed Texas’ Medicaid 1115 Transformation Waiver through 2030, a move supported by TMA. The waiver is a critical part of Texas’ health care safety net that, among other things, ensures an annual $3.8 billion to offset uncompensated care in the state.

However, the renewal comes with important caveats for rural care, says Nancy Dickey, MD, executive director for the Texas A&M Rural and Community Health Institute in College Station. It appears to favor larger, more complex hospital systems, meaning rural hospitals might not benefit as much as they have in the past.

“Each time that we do a [waiver renewal], we have to renegotiate with CMS what that will look like, and the individual programs from the different regions are not going to be continued by CMS,” said Dr. Dickey, a past president of the American Medical Association. “So, the question is whether our rural hospitals have both the infrastructure and the patient clientele that will allow them to tap into the new distribution formulas.”

Also, the new waiver will no longer include funding for the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program, which has supported innovative health care initiatives for Medicaid and uninsured populations, Dr. Dickey says.

DSRIP, which expires in September, funded $2.5 billion in fiscal year 2021 for programs designed to improve primary care, preventive care, mental health, and other efforts targeting Medicaid and low-income patients, including those without health insurance.

Rural hospitals and health care professionals may be able to reestablish some of those health initiatives, but that is not clear, Dr. Dickey says. Moreover, because DSRIP funding could be used for uninsured patients, it provided an important resource for that population.

“Many of the programs that were the most visible and helpful [to low-income rural patients] were through the DSRIP, and there will be no DSRIP,” she said.

Even rural areas with a hospital and local physicians struggle to get and keep health care professionals, Dr. Ahmed says. His local hospital in Big Spring has 40 beds, but the nursing shortage makes only 10 to 12 beds available, and the number of physicians who live locally has declined for years. (See “Short Staffed,” page 26.)

Among other health care professionals, nursing shortages tend to get the most attention because they can have the most dramatic impact, says Alpine family physician Adrian Billings, MD. But nurses are not the only members of the health care team in short supply. Rural areas also have too few lab technicians, ultrasound technicians, and phlebotomists – among other professionals – and that can result in lower-quality care for patients, he says.

“The analogy I make is that rural health care organizations like critical access hospitals or federally qualified health centers or rural clinics, they’re like small football or soccer teams,” he said. “If somebody gets sick, whether it be a nurse or a physician or an advanced practice clinician or a pharmacist or whatever, there may not be anyone else on the bench to jump into the game. Or, if you do pull somebody in, it may not be in the area where they’re strongest.”

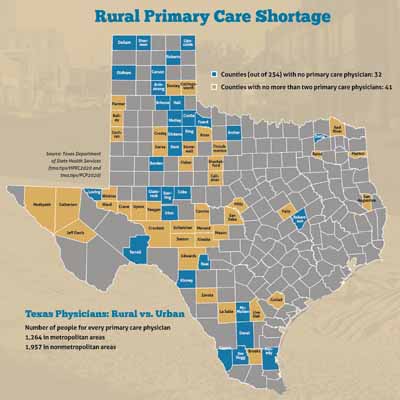

Texas’ chronic physician shortage has been alleviated somewhat by the fact that the number of primary care physicians rose 9.4% between 2011 and 2021, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services. But the ongoing physician shortage is especially pronounced in rural areas. (See “Rural Primary Care Shortage,” page 23.)

Short term, loan-forgiveness programs are one of the most effective recruitment tools for rural medicine, says Dr. Gibson of UNTHSC. They help physicians and health care professionals ease their loan burden in exchange for working in an underserved rural area.

“A lot of students are finishing with extreme debt, and I think [it would help] being able to offer incentives for repayment,” he said.

Texas medical schools diversify their student bodies in part by encouraging middle school and high school students from underrepresented groups – including students with a rural background – to go into medicine.

But medical schools need more programs designed to identify those young students and then encourage their progress through residency, Dr. Billings says. And that approach needs to be expanded to find rural recruits for other health care professions, including nursing, pharmacy, social work, dentistry, and behavioral health.

“We know by and large that rural-born or educated students are the ones most likely to return to their own rural communities because of their roots,” he said.

Texas medical institutions already have sharpened their focus on rural care.

Dr. Gibson’s rural medical education program at UNTHSC, which started in 2010, provides about 20 osteopathic medical students with extra curriculum each year designed to acquaint them with the realities of rural medical practice – including hospital rotations in rural settings. Up to 50% of these students go on after their residencies to settle in communities with 20,000 to 50,000 people, he says.

Three medical institutions provide rural training tracks for residents interested in rural practice – TTUHSC at the Permian Basin in Odessa, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler, and The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. These programs put physician trainees in small-town hospitals so they can learn firsthand what medical practice is like.

About one-quarter of the residents who take part in the TTUHSC program end up practicing in rural areas, says Timothy Benton, MD, regional dean for the TTUHSC Permian Basin campus. Without that experience, young physicians often are intimidated by rural medicine and are unlikely to explore it as a career option.

“You have to take care of a broad spectrum of illness and severe illnesses [in rural practice],” he said. “You could be involved in trauma care, and you’re the first to arrive at the heart attack and the stroke. … Training programs like this help [physicians] to overcome that barrier.”

In 2019, TMA strongly supported House Bill 1065 in the Texas Legislature, which established a grant program designed to encourage rural hospitals to set up rural residency programs. Although the bill passed, the state has not yet funded it.

Help for rural communities may also be on the way from two new medical schools – Sam Houston State University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Conroe, which opened in 2019, and The University of Texas at Tyler School of Medicine, which opens in 2023. Both are dedicated specifically to addressing the shortage of physicians in rural East Texas.

And help has already arrived in the form of telemedicine. Unlike other Texas physicians, many in rural areas have a background in this technology that predates COVID because of its ability to span great distances.

Yet rural physicians often struggle the most with delivering that service because many patients still do not have access to broadband internet, Dr. Dickey says.

“You really need broadband access to make telemedicine a functional solution,” she said. “And it won’t surprise you that the places that most need broadband penetration are the places where we most need health care.”

In 2021, Texas lawmakers – with TMA’s strong support – approved House Bill 5, which created a broadband map for the state and a plan to funnel federal dollars into broadband projects. Also, the Texas House is studying ways to improve broadband access as part of its interim charges for the legislative session.

In addition, the Telehealth Initiative, of which TMA is a member, has launched a series of projects designed to help Texas physicians use telemedicine more effectively. (See “The Telehealth Initiative,” July 2021 Texas Medicine, pages 20-25, www.texmed.org/TheTelehealth

Initiative.) However, even with improved access and education, telemedicine still faces potential obstacles in rural areas, Dr. Dickey says. For primary care physicians in rural counties, one of telemedicine’s best uses is as a means to make referrals to the specialists – like neurologists and cardiologists – who seldom live in sparsely populated regions.

But rural patients might never get connected to those specialists if enough primary care physicians don’t stay in rural areas to guide them, she says. And in many cases – such as delivering babies – there’s no substitute for an in-person physician.

“Telemedicine may be the answer [to the problems of rural health],” she said. “But telemedicine is probably a stronger answer if you have strong primary care in a community and primary care partners with virtual specialty care – rather than thinking you can provide all of the care by telemedicine without a physician on site.”

Tex Med. 2022;118(7):20-27

Aug/Sept 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page