On Dec. 21, 2020, Congress triggered a small-but-significant thaw in the freeze on federal funding for graduate medical education (GME). After 25 years, lawmakers approved a tiny increase in the number of residency positions funded by Medicare.

This crack in the ice centered on a little-noticed section of the $900 billion spending package designed to stimulate the U.S. economy and combat COVID-19. The package provided $1.8 billion to fund 1,000 new Medicare-supported residency positions over a five-year period.

The 1,000 positions will be doled out at a pace of 200 a year nationwide over five years. They will be targeted at priority communities, including teaching hospitals in rural areas, those in states with new medical schools, and those that serve communities with physician shortages.

The number of new positions is so small – in a country with nearly 140,000 existing residency positions – it’s possible that even a populous state like Texas might get few or none of them, says R. Armour Forse, MD. He’s a general and bariatric surgeon and chief academic officer at Doctors Hospital at Renaissance (DHR Health) in Edinburg, which sponsors five residency programs in partnership with The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV) School of Medicine.

“[It] was really a drop in the bucket,” said Dr. Forse, who also serves on the Council on Graduate Medical Education, the primary advisory body to Congress on GME that is part of the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration.

Even so, Medicare pays for 80% of all GME positions in the U.S., according to a June 2021 report from the U.S. Government Accounting Office (GAO). So, any increase in the number of GME positions is a welcome change, Dr. Forse says.

That small thaw may be the prelude to a much bigger shakeup in the rigid structure of GME funding, Dr. Forse says. The initial draft of Congress’ 2021 $3.5 trillion budget resolution called for $20 billion in new GME funding. In 2020, the U.S. spent $15 billion on GME, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The 2021 budget resolution, approved by both the Senate and the House of Representatives, did not include a specific dollar amount. The Senate instructions to committee budget writers instead call for “addressing health care provider shortages (graduate medical education).” The details of this potential funding increase were under debate as Texas Medicine went to press.

“It would be an immensely positive development if Congress approved additional funding for residency positions,” said Roberto Haddad, vice president and counsel for governmental affairs and policy at DHR Health, who has worked with Dr. Forse to improve Medicare GME funding. “It would provide hospitals all across the country with the ability to apply for and get new residency positions.”

The new federal interest in expanding the number of funded GME positions has been born of frustrations caused by

COVID-19, Dr. Forse says. Long wait-times to see physicians and shortages of emergency department and hospital beds have created a growing awareness that the physician shortage ultimately has to be fixed at the federal level.

“This is what the pandemic has done – emphasize the shortage of health care professionals – not just doctors but nurses and other health care professionals,” he said. “And the country is realizing that we need to fix this now.” (See “An Overworked Force,” page 30.)

Loosening the bottleneck

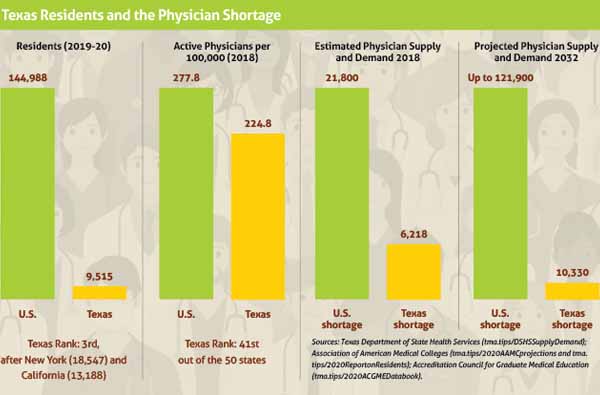

Numerous medical organizations – including the Texas Medical Association – have called for expanding the physician pipeline in recent years because population growth nationally has made the shortage so acute. (See “Texas Residents and the Physician Shortage,” page 28.)

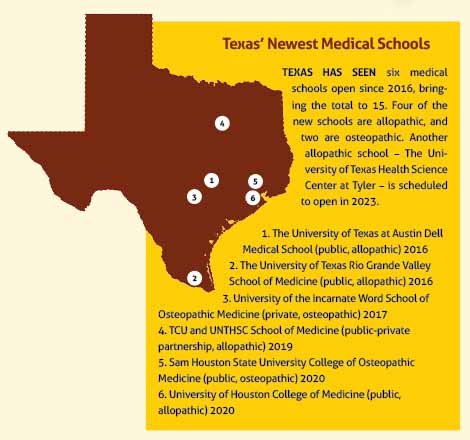

In response, six new Texas medical schools opened their doors beginning in 2016 (with another slated to open in 2023), and some of the nine older medical schools have increased their class sizes. (See “Texas' Newest Medical Schools,” page 29.)

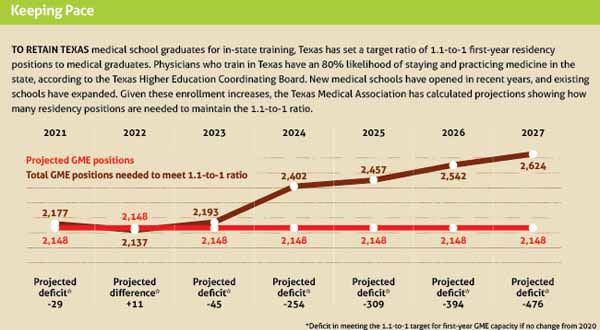

The number of Texas medical school graduates is rising, with more than 2,000 expected to receive a diploma in 2023, up from about 1,700 in 2018, according to TMA data based on reports from medical schools. (See “Keeping Pace,” below.)

But residencies – the intensive training positions that come after medical school – have remained a bottleneck in the pipeline, says Lisa Nash, DO, associate dean for education programs at the University of North Texas Health Science Center Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine in Fort Worth.

Despite improved funding from the state and from hospitals on GME, the pace of GME growth has been held back by the limited Medicare funding hospitals get for residencies, Dr. Nash says.

“The challenge has been the GME side because our funding is capped at the federal level,” she said. “Hospitals that [already] have GME are not able to expand.”

The GME bottleneck and the physician shortage have had the same point of origin: the U.S. Balanced Budget Act passed by Congress in 1997. To contain costs, that law froze resident positions funded through Medicare at 1996 levels for hospitals that provided training at that time. The size of the caps varies broadly, but in some cases, large hospitals have been stuck with longstanding caps of only a few residency positions.

They can fund new training positions in other ways – this includes through state and local funding or by paying for the residency position themselves.

But Medicare’s contribution has not budged for the majority of programs – until the 2020 stimulus bill created the 1,000 new residency positions. For the first time in many years, it allows qualifying hospitals to open up their caps just a bit to create new Medicare-funded residencies.

The five-year countdown

So-called “naïve” hospitals – those without GME programs – are eligible for new Medicare GME funding for the residency spots they create. But the moment a resident walks in the door for work, that hospital is on a five-year clock to set its cap, Dr. Nash says.

“It’s crazy,” Dr. Nash said. “That means you have to build out this whole elaborate GME infrastructure in a really short period of time in order to not end up with a cap that restricts your funding for the future. When I talk to a hospital about residency programs, what most of them would prefer to do is start one primary care residency program. [They say,] ‘Let’s get that one well established, and then we’ll move on to the next one and the next and the next.’ That makes a lot of sense, but you can’t do it that way or you lose your opportunity to capture funding.”

Dr. Forse saw just how crazy it was when he helped Doctors Hospital at Renaissance establish residency programs in partnership with the UTRGV School of Medicine.

The DHR Health effort began in 2015, one year before the medical school opened in 2016. About 30% of people in the Rio Grande Valley live in poverty, and with hospitals already stretched thin taking care of them, a lack of resources in the region quickly emerged as a major impediment to starting a new residency programs.

Before the hospital could even submit an application to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the accrediting body for residency positions, it had to build facilities such as classrooms and call rooms.

“More importantly, you have to have faculty – physicians or surgeons – who not only practice medicine but are able to teach,” he said. “In underserved areas, you’re starting off with not having enough doctors.”

Addressing all these steps takes “months or years,” Dr. Forse said. At the same time, the hospital must pay for this process up front because the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) does not begin to reimburse the program until after residents start to work.

“If you’re in a big city and you’re a big academic center, etc., you’ll have dollars that you can use to build training programs and open the positions using other resources,” Dr. Forse said. “But when you’re in underserved areas, you’re already behind the eight ball because you don’t have a lot of additional dollars around to build training programs. That’s why the underserved areas and rural areas really depend on CMS dollars to get these training programs up and running. Because they’re expensive, and there’s a lack of those other funds.”

Resetting the GME clock

Hospitals that can’t make their caps high enough to provide an adequate number of residents frequently supplement the Medicare money with their own. A June 2021 GAO report found that 70% of U.S. teaching hospitals train more residents than Medicare reimburses them for and that most of these hospitals do this at their own expense. (tma.tips/2021GAOresidencies).

Of course, the residency programs that most need to supplement their Medicare caps – those in underserved and rural programs – find it difficult to come up with the extra money. Since 2014, thanks in part to TMA advocacy, Texas has supplemented Medicare funding by providing expansion grants for hospitals looking to boost their number of positions. The growth could come through new programs or adding positions to existing ones. The grants pay $75,000 of the $150,000 most studies show is required to pay for one residency spot, according to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. That $150,000 covers all annual costs – benefits, health care, salary, and other related expenses. Texas also offers GME planning grants of $250,000 per recipient to help naïve hospitals through the assessment phase, among other issues. (See “GME Momentum,” April 2021 Texas Medicine, pages 20-25, www.texmed.org/GMEMomentum.)

Underserved and rural programs also are hampered by the fact that Medicare’s payments, when they do arrive, never cover the upfront costs incurred by hospitals in setting up GME programs, Dr. Forse says.

Even after eating those costs, establishing residency programs can be attractive because teaching hospitals tend to attract talented faculty and students, and that can lead to higher-quality health care. For instance, a Jan. 28 JAMA Open Network study of 1,298 academic hospitals found that more GME funding led to reduced patient mortality (tma.tips/JAMA-GME).

“But it takes years to make up that investment,” Mr. Haddad said.

Setting up residency programs has another big advantage: About 60% of the graduates tend to practice in the region where they trained, Dr. Forse says. That makes them a valuable tool to improve care in underserved and rural regions.

But the five-year window for building programs simply is not long enough to fully establish GME programming, he says.

“When you’re trying to build these in underserved areas or rural areas, five years goes by really fast, and that can limit the number of positions you have and that CMS will support you on,” he said.

The increased funding, like the kind proposed in the $3.5 trillion budget resolution, would help, but hospitals also need more time to get GME programs up and running, Dr. Forse says.

He and Mr. Haddad helped write H.R. 4014, The Physician Shortage GME Cap Flex Act, which would give qualifying hospitals in underserved and rural areas 10 years, not five, to establish their Medicare cap for residencies. As of this writing, the bill, sponsored by U.S. Rep. Raul Ruiz, MD (D-Calif.), awaits a committee hearing.

Providing enough residencies for Texas medical students remains key to addressing the physician shortage, Dr. Nash says.

Medical students who do their residency training in Texas have an 80% likelihood of staying and practicing medicine in the state, according to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. So, helping in-state residency programs increase the number of positions would take a big bite out of the state’s shortage, Dr. Nash says.

Each year at the Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine, “we have roughly half our class leave the state for residency,” she said. “Of those, almost all of them would have preferred to stay in Texas had they been able to secure a residency position.”