It Didn’t Have to Be

Eugene Hunt, MD, estimates he’s attended the delivery of thousands — “three, four, five thousand?” — of infants in his 35 years of practice as a Dallas obstetrician.

Eugene Hunt, MD, estimates he’s attended the delivery of thousands — “three, four, five thousand?” — of infants in his 35 years of practice as a Dallas obstetrician.

Two “sad, sad, sad” cases stick in his mind. In one, the mother died just before going into labor; Dr. Hunt performed a cesarean section and saved the twins inside her body.

The other case has changed the way he monitors and cares for his patients weeks and months after they’ve taken their newborns home.

“You bet your boots,” Dr. Hunt said as he recounted the tragedy. “I have gone out and picked up patients from their homes and taken them to psych wards. I’ve brought them back to my office and called psychiatrists. The idea that one day after I talk to a lady she commits suicide is an experience that I can never ever forget.”

After a routine pregnancy and delivery, the lady — we’ll call her Sharon — took home a “beautiful baby girl.” Some six to eight weeks later, she called Dr. Hunt to talk and shortly after showed up at his office.

“She seemingly looked fine, she didn’t look all distraught,” he said. “She began telling me about some of the challenges of the baby and how the baby seems to cry a lot. … She was overwhelmed, and it was kind of difficult.”

Dr. Hunt says he offered Sharon reassurance, telling her that her experience is common among new mothers and won’t last. “A better day is coming,” he said.

Then the conversation turned in a way that Dr. Hunt unfortunately recognized only in hindsight.

“She at one point made that little suggestion that someone, maybe family, had actually shot themselves. And then she said ‘I would never actually do anything like that.’ Forever, if anybody tells you they will never do something, you perk up.”

After more supportive conversation, he sent Sharon home, where her husband and mother were helping her care for the baby. Early the next morning, Dr. Hunt recounts, she put the infant in bed with her husband, walked to the garage, took a pistol from the glove compartment of her car, and shot herself.

Initially angry and disappointed at Sharon’s suicide, Dr. Hunt says a conversation with a colleague helped him understand the catastrophe. “He was thinking from her perspective, ‘She is so overwhelmed, she is so distraught, and post-partum depression can certainly put her there.’”

Post-partum depression is not the “baby blues” that 50 to 60 percent of mothers experience in the first few months after delivering a baby. As many as one in seven new mothers acquire the serious psychiatric disorder known as post-partum depression. It’s the tipping point where the physical, emotional, hormonal, and psychological changes surrounding pregnancy and birth gang up to create a dangerous mental illness in the mother.

“It is so overwhelming to the individual with the multitude of changes going on in every bit of their being that you’ve got to watch them,” Dr. Hunt said. “We must address every lady who has a baby, when we’re discharging them from the hospital, we better talk about post-partum depression. It’s recognized. This is real. And you can save lives when it’s talked about properly.”

Sharon’s story is a regular reminder. “I had to wonder, what might I have said? What might I have done? This is part of the medical profession’s burden when we have patients who do such things as this,” he said. “What would have kept this tragedy from happening?”

Childbirth, one of life’s greatest joys, can morph into tragedy when the infant’s mother dies. Even one death is one too many. Thankfully, most maternal deaths — 80 percent in one state study — are preventable. And for every new mother who dies in Texas, another 50 to 100 experience serious, life-threatening conditions. Building on the work of state and national maternal health experts, Texas physicians propose a clinically proven list of interventions to counter this troubling trend. Physicians, hospitals, nurses, and other members of the health care team have rightly assumed responsibility to implement some of these recommendations. Others require action from the Texas Legislature — who, in foresight, already established the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force — to ensure that at-risk mothers have the services and resources they need. Together, we can make sure it’s safe to be a mom in Texas.

More Access, Less Confusion

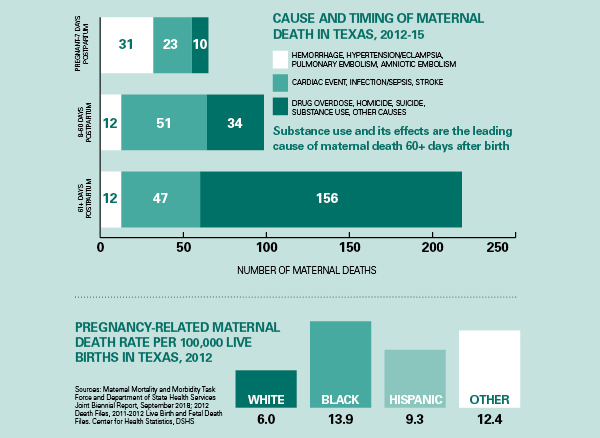

Medicaid paid for 52 percent of all births in Texas in 2015, and most new mom’s Medicaid coverage ends two months after she delivers her baby. A Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) study found that 382 Texas mothers died within a year of giving birth between 2012 and 2015. More than half of these deaths occurred later than two months after the baby was born. The top known causes of death in these cases included drug overdose, cardiac events, homicide, and suicide. Medicaid provides comprehensive care for eligible women from the time they find out they are pregnant until 60 days after delivery. When Medicaid pregnancy-related coverage ends, Texas automatically enrolls adult women into the Healthy Texas Women (HTW) program, which connects them with preventive health services, including contraceptive services, and basic primary care. HTW provides coverage to low-income women of reproductive age before pregnancy, too. But it provides little or no treatment for acute or chronic conditions, leaving women with complex medical needs, such as diabetes, substance use disorder (SUD), or postpartum depression, without coverage for specialty care.

Low-income women ineligible for Medicaid may qualify for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Perinatal Program (CHIP-P), which covers up to 20 prenatal visits, labor and delivery, and two postpartum visits. Women whose CHIP-P coverage ends can obtain preventive health care services via the Texas Family Planning Program. The underfunded Substance Use Disorder Services for Pregnant and Postpartum Women provides the services listed in its name but isn’t integrated into a system that provides care for other medical services. Transitioning from one program to another is difficult and confusing, and only Medicaid provides comprehensive benefits. Women, families, physicians, and providers are often challenged in how to fully access needed services before, during, and after pregnancy.

TMA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

- Direct the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) to pursue a federal demonstration waiver to increase access to comprehensive services for low-income women before, during, and after pregnancy, including substance use treatment and behavioral health care. Federal funds could provide more consistent and continuous coverage for women of childbearing age and eliminate some of the confusing maze of support systems. At a minimum, the waiver should target high-risk women, including women with a prior preterm delivery or with a chronic medical condition that puts them at risk for pregnancy-related complications.

- Streamline and automate the transition from Medicaid to HTW for adolescents aging out of Medicaid and CHIP, and for CHIP-P enrollees to the Texas Family Planning Program.

- Ensure women receiving SUD treatment in a chemical dependency treatment program can easily and quickly obtain preventive, primary, and specialty care.

- Increase SUD treatment capacity by allocating dollars to promote and establish community-based treatment options.

Maternal Safety Begins With Moms-to-Be

Texas must embrace public and private efforts to increase awareness of the importance of community-based efforts that promote early entry into prenatal care and ensure essential follow-up care after delivery. In addition, the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force reported that black women had a 2.3-times higher rate of maternal death than white women. Any public health efforts must target this at-risk population to provide the best care for all Texas mothers.

TMA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

- Support a comprehensive public education program on the importance of prenatal care, and eliminate Medicaid eligibility barriers that stymie timely enrollment.

- Support common sense efforts to reduce risk factors associated with maternal death and disease, such as initiatives to reduce smoking before and during pregnancy.

Well-Spaced Pregnancies Are Safer Pregnancies

In Texas, approximately half of pregnancies are unintended. Women whose pregnancies are unintended are more likely to have a short interval between pregnancies — 18 months or less — which increases health risks to mother and child. Unintended pregnancies also increase Medicaid costs. Medicaid pays $3.5 billion per year for pregnancy- and delivery-related services for mothers and infants in the first year of life. Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), such as implants and intrauterine devices, are 20 times more effective than other methods, yet the latest national data indicate less than 12 percent of women rely on LARCs. Three of Texas’ disjointed women’s health programs cover LARCs as a benefit, but usage among women who want them remains low. Many physicians, hospitals, and clinics do not offer same-day availability of LARCs because of low payment, logistical hurdles, and insufficient training on how and when to use them.

TMA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

- Reduce red tape and payment barriers that are preventing widespread adoption of LARCs.

- Provide funding to make LARCs available immediately following delivery to women enrolled in CHIP-P.

- Increase teen access to contraceptive care by allowing adolescents to enroll in both CHIP and HTW (with parental consent.)

Get the Numbers Right

The lack of accurate data — including inaccurate and incomplete death certificates — has significantly complicated the state’s quest to identify the root causes of Texas’ maternal health problems. Meanwhile, physicians treating women before, during, or after their pregnancies frequently do not have access to their patients’ complete social or medical history because the myriad of electronic health records (EHRs) in use are not interoperable. [See Section 1: Stop the Interference.]

TMA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

- Support comprehensive efforts to improve the state’s surveillance of maternal mortality and ensure Texas’ maternal death records have accurate information on all of the factors associated with maternal deaths.

- Require improved interoperability among EHRs to eliminate barriers to the exchange of health information critical to providing quality maternal and postpartum care.