System blackouts. Ransom notes. Lost revenue. Compromised patient care.

Once straight from physicians’ nightmares, these threats are now reality for their practices as cyberattacks infiltrate health care.

Just ask Texas Medical Association President Ray Callas, MD. His Beaumont infusion center, as of this writing, had not received claims payments since Feb. 18 following the Feb. 21 ransomware cyberattack on Change Healthcare, a health care technology company owned by UnitedHealth Group under its subsidiary, Optum.

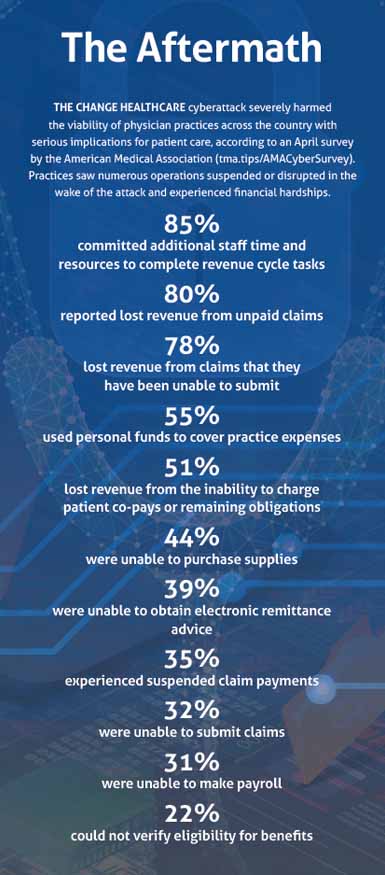

The attack caused a shutdown of Change Healthcare’s clearinghouse for medical claims, causing significant financial and operational disruptions to physician practices across the country, including to billing services, eligibility checks, insurance approvals, and the exchange of payment and health information via clearinghouses. (See “The Aftermath,” below.)

These challenges, combined with the loss of revenue, forced Dr. Callas to take out a local bank loan to keep the center operational, a move that left him “extremely frustrated and worried about his fellow physicians.”

“I’m not the only physician who has been affected,” the Beaumont anesthesiologist said. “The fallout of this attack and those like it have forced many clinicians – and other health care professionals – to either dip into personal funds to cover practice expenses or seek funding assistance, as I did. It is ruining practice operations across the country.”

San Antonio orthopedic surgeon Adam Bruggeman, MD, testified on his own similar experience before the U.S. House Energy & Commerce Committee’s Health Subcommittee in April, highlighting several concerns shared by TMA.

As this story went to print, the Change Healthcare attack – and its consequences for physician practice viability, industry consolidation, and patient access to care – was the subject of the congressional hearing, the first of several anticipated on the topic, as UnitedHealth Group faced mounting pressure to account for the attack.

“The Change outage was disruptive to the business of my practice, but most importantly it was disruptive to my patients,” Dr. Bruggeman testified. “Every minute my staff spent trying to reconcile [electronic remittance advice] with received payments, assessing which patients received incorrect bills, [and] resubmitting prior authorizations is time taken away from patient care.”

The more medical practices and health care organizations fall victim to ransomware cyberattacks, the more important it becomes to prevent them, says Manish M. Naik, MD, chair of TMA’s Committee on Health Information Technology.

A June 2021 survey by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found 34% of medical professionals fell victim to a ransomware attack between January and February of that year.

What’s more, 41% of respondents, even those spared from ransomware attacks that year, said they fully expected to experience an attack in the future, and only a quarter of clinicians felt confident that their systems were safe against future attacks.

Meanwhile, ransomware payments exceeded $1.1 billion in 2023 across various business sectors, according to the cryptocurrency-tracing firm Chainalysis – the highest amount the company has measured in a single year and nearly double the year before.

“Each successful ransomware attack on medical organizations encourages the next hacker to target health care practices,” Dr. Naik said. “Having the appropriate infrastructure in place to protect your data is becoming increasingly necessary.”

Data held hostage

The Austin internist cautions that ransomware attacks can be delivered via multiple platforms, such as in email attachments or links within an email. Malicious attachments can include documents, zip files, and executable applications, and suspicious email links can bring users directly to websites that are used to place malware on a system.

Similarly, “phishing” email scams can give hackers access to internal business systems that could reveal confidential information like credit card numbers, personal identity data, and passwords. Often these emails appear to come from real companies or trusted individuals.

From there, hackers steal electronic patient data, even encrypted information; block the practice from accessing it; and demand a ransom for its return, much like “a hostage situation,” according to Shannon Vogel, TMA’s associate vice president of health information technology.

If that data aren’t backed up, practices don’t have much leeway. At that point, they can either hope the data can be retrieved by law enforcement or move forward without patient records.

“It’s vital that practices talk to their [electronic health record] and other vendors about redundant systems so that all is not lost,” Ms. Vogel said. “Otherwise, it would be like starting from scratch.”

Additionally, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) doesn’t recommend paying the ransom. There are no guarantees practices will get their records back intact and, if the hacker happens to be on a special government list that includes terrorists, narcotics traffickers, and others, paying that criminal can leave practices – the victim – open to potential civil penalties, per a 2020 U.S. Treasury Department memo (tma.tips/TreasuryCyber).

According to the memo, Americans are barred from “engaging in transactions, directly or indirectly, with individuals or entities” listed on a specific Treasury Department watchlist, such as targeted companies acting on behalf of targeted countries, as well as noncountry-specific terrorists and narcotics traffickers.

People who do engage with such entities may face civil penalties, “even if [the person] did not know or have reason to know [he or she] was engaging in a transaction with a person that is prohibited” by the department, according to the memo.

Dr. Naik says practices should attempt to avoid that situation at all costs, instead cautioning that “vigilance is the best defense against phishing or other ransomware scams.”

“Having antivirus and anti-malware [software] in place to guard against cyberattacks is still important, but preventing ransomware today is more a matter of being smart and knowing how to recognize malicious communications disguised as legitimate ones,” he said. “No passwords on sticky notes, no opening of suspicious emails. And those are inexpensive ways to safeguard your system.”

Leaving the cybersecurity light on

Cathy Bryant, manager of cyber consulting services for the Texas Medical Liability Trust (TMLT), which offers medical liability coverage to TMA members’ practices, equates a lack of cybersecurity to leaving valuables unguarded.

“If a burglar is driving up and down the street trying to pick a house to break into, they’re going to look for the one that doesn’t have any lights on,” she said. “You want to be the practice that has their lights on, so to speak.”

Those “lights” include:

• Only opening expected emails from known senders. A cybercriminal can impersonate the sender or the computer belonging to that sender, which may be infected without his or her knowledge.

• Avoiding email attachments from an unknown, suspicious, or untrustworthy source. If the sender is unfamiliar to the practice, physicians and staff should not open, download, or execute any files or email attachments.

• Not opening any email attachments with questionable subject lines. If the attachment may be important, save the file to a hard drive before it’s opened.

• Exercising caution when downloading files from the internet and making sure the website is legitimate and reputable. If there are any doubts, don’t download the file.

• Contacting a company via its published customer service contacts to find out whether an email is legitimate before replying to the email or clicking on any links.

• Using two-factor authentication.

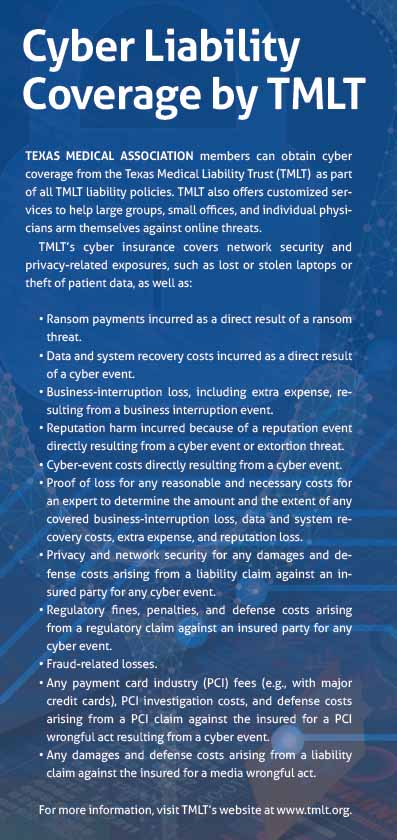

Physicians also can obtain cyber liability coverage, which typically includes network security and privacy-related exposures such as lost or stolen laptops or theft of patient data. (See “Cyber Liability Coverage by TMLT,” below.)

With TMLT, for instance, if a policyholder reports a ransomware attack, staff assign a cyber attorney to handle the case and to determine whether the practice needs a forensic examination to assess the threat, Ms. Bryant says. That examination is typically expensive, but timely reporting of any cyber incident is important to get the practice back to normal operations, she notes.

Moreover, staff cybersecurity training should be conducted at the time an employee is hired and then periodically throughout the year, she adds.

Practices should hold cybersecurity awareness training every four to six months, per an August 2020 study by the advanced computing system company USENIX. The study found employees who undergo cybersecurity training every four months can spot phishing emails in between training, but after six months those employees forget what they have learned.

Physicians can either host these trainings themselves or work with a third-party vulnerability-testing service, which can educate staff through email tests that mirror real-world phishing scams. If staff click on the test links, they are notified of the error and required to complete mandatory retraining.

Ms. Vogel adds formal written policies regarding cybersecurity and accountability should be created and shared with staff at the time of hire and discussed throughout the employment term. These policies should outline cybersecurity best practices. For example, unauthorized software should never be allowed on practice devices.

If those tactics fail and a practice falls victim to a ransomware attack, it should immediately contact law enforcement or the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center to report a ransomware event and request assistance (tma.tips/InternetCrimeComplaint). These professionals work with state and local law enforcement and other federal and international partners to pursue cyber criminals globally and to assist victims. The agency will help practices, insurers, or third parties assisting them to resolve the situation.

Dr. Naik is “hopeful physicians won’t need to go down that road.”

“It may sound a bit paranoid, but physicians need to start thinking like cybercriminals,” he said. “The main way to avoid cyber incidents is by educating your internal staff about safe security practices.”