Texas has taken some big steps to combat maternal death and illness in recent years, says Houston obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-Gyn) Carla Ortique, MD, vice chair of the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee. But there’s no doubt the

state has many more steps to go.

That was highlighted by one of the Texas Medical Association’s biggest wins in the 2021 regular session of the Texas Legislature, when medicine’s longtime advocacy resulted in an extension of Medicaid coverage for postpartum maternal care from two to

six months under House Bill 133.

While the longer time is welcome news, the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee recommends that health care coverage be extended to 12 months postpartum, Dr. Ortique says. That helps physicians identify and properly manage health conditions

before they become life-threatening.

This partial victory is just one of many that shows promise in addressing a major public health priority for TMA and the state. In recent years, Texas has had a hard time even getting an accurate assessment of maternal mortality and morbidity. (See “Counting

on Women’s Health,” page 28.)

That has changed in large part because of the review committee’s work. But it is clear that Texas still has a high maternal mortality rate, says San Antonio OB-Gyn Patrick Ramsey, MD, chair of TMA’s Committee on Women’s, Reproductive, and Perinatal Health.

“We feel pretty confident that [the rate of maternal mortality] is still climbing despite a lot of efforts that have started,” Dr. Ramsey said. “We still haven’t finished a lot of those efforts, and a number of them that have yet to be initiated.”

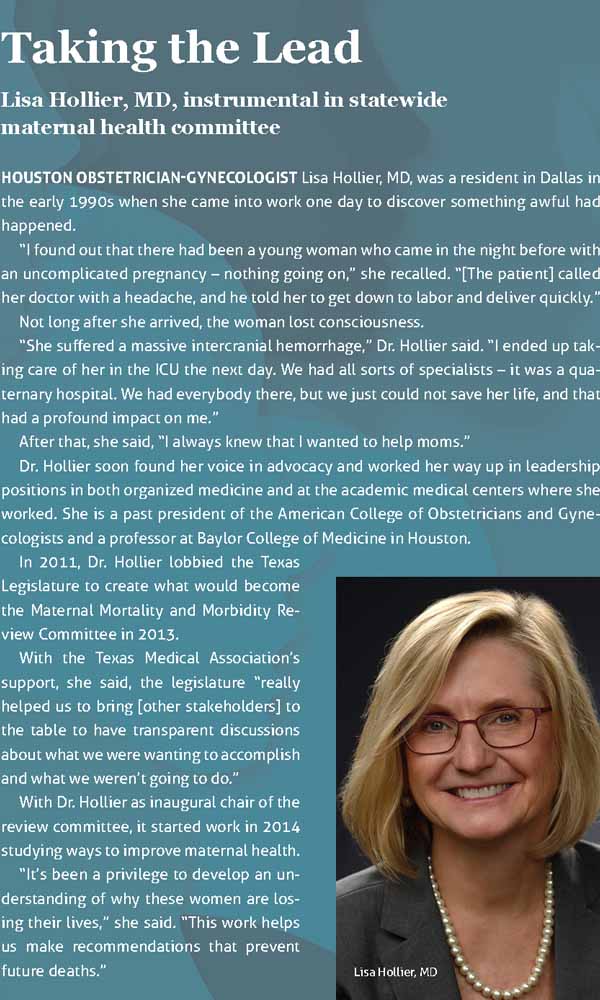

And while death during pregnancy or the year after pregnancy affects about 150 Texas women each year per state data, the problem is much larger than that group, says Houston OB-Gyn Lisa Hollier, MD, chair of the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity

Review Committee.

“The review committee found that 89% of the pregnancy-related deaths were preventable,” she said. “So that’s a lot of women who did not need to die.”

And those deaths are a sign of much a much larger problem for the health system: For every pregnancy-related death, 50 to 100 women have pregnancy-related illnesses, Dr. Hollier says.

“The tip of the iceberg is these women who lost their lives,” she said. “And everything else under the surface of the water are the thousands of women who have severe complications with ramifications that can be – if they survive – lifelong. The interventions

that we put in place will prevent that as well.”

A solvable problem

House Bill 133 provided women enrolled in pregnancy-related Medicaid with six months of postpartum coverage, an increase from the previous two months. Although the law took effect Sept. 1, Texas will need to obtain a federal Medicaid waiver to enact the

change.

The 12-month postpartum coverage policy is so widely accepted, however, that the American Medical Association adopted a policy in 2019 in support of it.

“We were happy that the legislature extended coverage for six months, but the evidence supports that 12 months is the critical number,” Dr. Ortique said.

Meanwhile, the state’s biggest effort involves the adoption by Texas hospitals of guidelines set up by the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM), a national program overseen by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists along with

the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration.

Texas launched TexasAIM in 2018, patterning it after a California initiative credited with lowering that state’s maternal death rate from 16.9 deaths per 100,000 to 7.3 between 2006 and 2013, according to the California Department of Public Health. (See

“AIMing to Save Lives,” April 2019 Texas Medicine, pages 21-23, www.texmed.org/AIMSavesLives.)

AIM came about because California health leaders in 2006 had hospitals study each pregnancy-related death and then identified ways to prevent future deaths. Those lessons were later packaged into bundles – or collections of best practices – for hospitals

to follow.

So far, 98% of Texas hospitals offering delivery services have introduced two AIM bundles – on maternal hemorrhage and hypertension. But several more bundles remain to be adopted, including those dealing with care for women with cardiac conditions and

those with opioid use disorder.

There are no data yet showing the impact of the AIM bundles on maternal death or complications in Texas, says Dr. Hollier. But many hospitals using the bundles report much smoother treatment for patients.

“Some of them [had stories] about having the safety drill [for hemorrhage] at their hospital and then having a patient come in with a massive hemorrhage and being able to work as a team and take care of her, feeling so much more confident that they were

able to do a really good job because of the training,” she said.

Greater buy-in

OB-Gyns typically face the lion’s share of cases involving maternal mortality and morbidity, especially problems like hemorrhage, Dr. Hollier says.

But combating other factors tied to maternal death and illness require buy-in and greater awareness from many specialties, she says.

“There could be a woman who comes in [to a physician office or emergency department] five days postpartum, and her consciousness is altered because she has severe hypertension,” she said. “Her treatment may be different if you know she’s been recently

pregnant.”

That buy-in also requires understanding that maternal illness and death have deep roots in patients’ social and lifestyle factors – or social determinants of health – that have to be addressed, Dr. Ortique says.

“We have to keep in mind that the AIM bundles impact facilities,” she said. “They do not necessarily impact individual family and community-level drivers [of maternal illness], and we know for certain that all of those contribute to maternal death.”

The main driver is lack of access to health care, according to the review committee’s 2020 biennial report (tma.tips/2020MaternalReport).

“In the reviewed cases, the lack of access to care or financial resources contributed to inadequate control of chronic disease as well as to delay or failure to seek care and adherence to medical recommendations,” the report stated.

That is why improving pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage to 12 months from six is so important – and why the review committee continues to make access to care a top recommendation for combating maternal death and illness, Dr. Hollier says.

“We need to ensure that comprehensive health care is accessible before, during, and after pregnancy,” she said. “That’s absolutely key.”

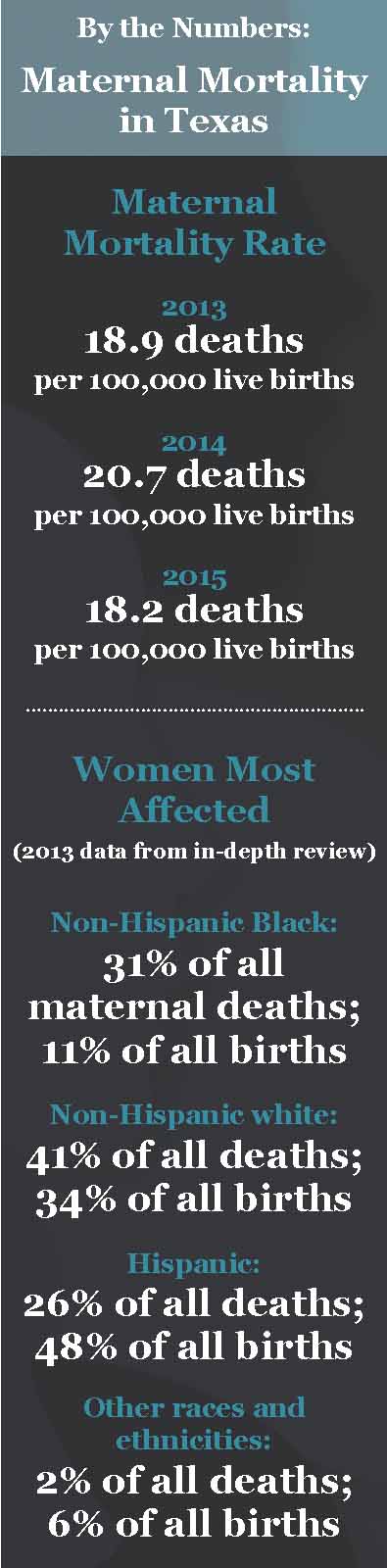

Physicians also need to understand that maternal illness and death affect some demographic groups more than others, she says. Black women especially are disproportionately affected. (See “By the Numbers: Maternal Mortality in Texas,” page 29.)

In many cases, the disparity has been caused by social determinants of health, Dr. Ortique says.

“You’re looking at transportation, food security, education – the kinds of things that undergird or are major drivers in the [maternal] outcomes,” she said.

Both Drs. Ortique and Hollier say that bias in health care also plays a strong role.

“Differences in outcomes can result from a number of different factors, but we think that structural racism and implicit and explicit bias also play a significant role in so much of women’s lives,” Dr. Hollier said. “We can work to ensure that all people

are treated by teams who understand their needs and whom they can trust.”

Tex Med. 2021;117(12):26-30

December 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page