Part of why COVID-19 has had such a devastating impact on the physician psyche isn’t just what’s been happening inside America’s medical settings since March 2020. It’s also what’s been happening outside – the same restrictions, business closures, and abridgement of fun and emotional release affecting the entire nation.

Those factors combined make COVID-19 a beast that medicine’s tired, overworked soldiers just can’t escape, says Temple emergency physician Robert D. Greenberg, MD.

“It used to be, even if we were getting our butts handed to us at work, you could go home; if you wanted to go out to a restaurant, see a movie, or even drop in at a bar, whatever, you could get away from it. But there’s no getting away from this one,” he said. “That’s one of the biggest differences, is there’s just no outlet. There’s no way to get away from it.”

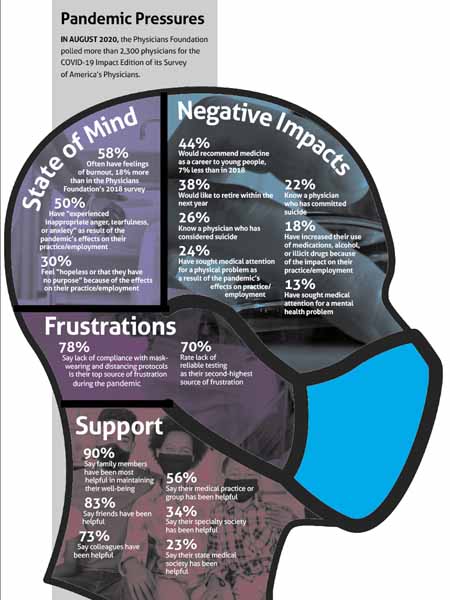

The malaise in physician practice long known as burnout – a term doctors increasingly balk at – has been exacerbated by the pandemic, as an extensive survey by the Physicians Foundation recently showed. It’s created its own stressors and made existing ones worse. (See “Pandemic Pressures,” page 19.)

Texas physicians have seen and felt that impact in their own ways. Although proposed solutions offer hope, doctors have toiled through everything from the day-to-day stress of overwork and the fear of contracting coronavirus themselves, to the lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), and the politicization of the virus. It’s added up to members of the profession becoming exhausted, fearful, and sometimes despondent.

“Their tanks are empty,” said Fort Worth allergist Susan R. Bailey, MD, president of the American Medical Association (AMA). “And once we start climbing out of this – and we will climb out of this – we have got to figure out ways to help physicians recharge and remain engaged and enthusiastic about taking care of patients, and not lose them from the profession altogether.”

Worn down

Among many other discouraging results, the survey found that half of physicians “experienced inappropriate anger, tearfulness or anxiety as a result of COVID-19’s effects on their practice or employment.” Nearly 60% of physicians said they “often have feelings of burnout.”

“Never would we have envisioned that a pandemic put an emergency physician’s job at risk,” said Dr. Greenberg, who works on the front lines, in an academic setting, and in administration. “But we have seen cuts in physicians’ jobs, cuts in their pay, and then additionally, everything is just more tedious to do when you’re wearing a mask – when you have to put on gown, gloves, mask, every time you go in a room, just trying to communicate with people, particularly those already compromised by illness or pre-existing conditions, is exhausting. Anything and everything is just draining our energy.”

The constant state of change, he adds, has “really, really” worn down his staff. “I’m incredibly sensitive about asking my guys to do anything above and beyond what is expected.”

When Austin family physician Erica Swegler, MD, a member of the Texas Medical Association’s COVID-19 Task Force, looked over the Physicians Foundation COVID-19 impact survey, she found it “absolutely reflective” of what she and other physicians in her orbit are experiencing.

Dr. Swegler has felt burnout before in her career. Because of it, six years ago, she left a group she had been a partner with for 16 years. She regained the joy of practicing medicine as a locum tenens physician. But as 2020 wore on, that burned-out feeling returned.

Dr. Swegler has been in independent solo practice for the past five years. From last March on, she says, the pandemic introduced extreme emotional fatigue. Uncertainty reigned, and new information came and went at a speed that made it hard “to keep up with things and know what was appropriate.”

And the pandemic exacerbated the already-considerable financial stressors of running a primary care practice, as patients either were temporarily barred from or were wary of coming to the office. Timeliness of payment, already an issue for many primary care physicians, continued, as did the medicine-wide scourge of insurers’ onerous prior authorization requirements.

For Dr. Swegler, telemedicine – which other doctors have seen as something of a savior for physician practices during the pandemic – has been an emotional drain. She wore down under the weight of “one call after the other after the other,” leaving her precious little energy after she’s done seeing patients.

“I love what I do. I can’t imagine doing anything else other than what I do,” she said. “But at 3:00, you’re looking at the clock going, ‘Well, how many more patients do I have left?’ and trying to see, ‘Well, when is my day going to be over?’ For me, it’s not so much during the day as having the motivation to do my after-clinic work.”

Dr. Greenberg says the added politicization of the virus – something not addressed in the Physicians Foundation survey – also has become an overarching frustration; COVID-19 has become an issue “fought in the media and by politicians,” creating outside pressures from patients that physicians don’t normally feel.

“We deal with direct-to-consumer advertising and Dr. Google on a regular basis. But that’s nothing compared to some of these almost-debates with patients or others about what’s the best or right thing to do, risk assessments, confusion over testing, and a plethora of proposed treatments,” he said. “Patients are already coming in with opinions that are ingrained and based upon nothing more than Facebook, some political figure, or actors’ opinions, all who think they know what to do and how to do it.”

The worst effects

The Physicians Foundation data show physician burnout prompts more than just frustration and anger.

A not-small percentage of physicians, 18%, say they’ve increased their use of alcohol, illicit drugs, and medication since the start of the pandemic. More than a fourth of doctors told the Physicians Foundation they know another physician who has committed suicide, while more than a fifth said they know a doctor who has considered it.

Sadly, Houston emergency physician and TMA President Diana L. Fite, MD, falls in the former category.

She served on an American College of Emergency Physicians committee with Manhattan, N.Y., emergency physician Lorna Breen, MD, medical director of the emergency department at New York-Presbyterian Allen hospital. Dr. Breen caught coronavirus near the beginning of the pandemic but went back to work soon after recovering, according to news reports. Her father told CNN she couldn’t make it through a 12-hour shift. She went to Charlottesville, Va., where most of her family lives, and was hospitalized for exhaustion.

Dr. Breen died by suicide on April 26, 2020. Her father told the New York Times, “She tried to do her job, and it killed her.”

“I definitely see some of the emergency physicians that I work with that are very, very tired and frustrated with having to put on all of the gear, the PPE, having to see patients that are so sick that they are getting worn down,” Dr. Fite told Texas Medicine. “I have seen that, and especially those that are worried about bringing illness home to their families.”

A less tragic, but still drastic, effect of the pandemic is early physician retirement. Dr. Bailey, president of the AMA, says aside from suicide, physicians prematurely ending their career is “one of the most concrete pieces of evidence” of burnout.

“We are seeing in our community physicians who have had to curtail their outpatient practices dramatically because of pandemic restrictions, and even though they may have taken advantage of all of the financial incentive programs that were available, they just don’t think that they can bring their practice back up to where it needs to be in order to be sustainable, especially now with cases going back up again,” Dr. Bailey said in December. “I’m aware of physicians that are just saying, ‘OK, that’s it. I’m hanging it up. I’m out of here.’ That’s a great concern that I have, is the impact overall on the physician workforce. … We’re a resilient bunch, and we can step up to a short or even a medium-term crisis. But this current level of stress just cannot be maintained as the new normal.”

A better term than “burnout”

One of the newer pieces of the movement to address physician burnout is reframing how the public perceives it, right down to its name.

Increasingly, physicians bristle at the term “burnout,” preferring to call it “moral injury” instead. A September 2019 report in the Federal Practitioner by three authors, including two physicians, explored the difference between the two terms.

The study explained that moral injury “occurs when we perpetrate, bear witness to, or fail to prevent an act that transgresses our deeply held moral beliefs. In the health care context, that deeply held moral belief is the oath each of us took when embarking on our paths as health care providers: Put the needs of patients first. That oath is the lynchpin of our working lives and our guiding principle when searching for the right course of action. But as clinicians, we are increasingly forced to consider the demands of other stakeholders – the electronic medical record, ... the insurers, the hospital, the health care system, even our own financial security – before the needs of our patients. Every time we are forced to make a decision that contravenes our patients’ best interests, we feel a sting of moral injustice. Over time, these repetitive insults amass into moral injury.”

The difference between moral injury and burnout is important, the authors said, because it reframes both the problem and the solutions for it.

“Burnout suggests that the problem resides within the individual, who is in some way deficient. It implies that the individual lacks the resources or resilience to withstand the work environment. Since the problem is in the individual, the solutions to burnout must be in the individual, too, and therefore, it is the individual’s responsibility to find and implement them. Many of the solutions to physician distress posited to date revolve around this conception; hence, the focus on yoga, mindfulness, wellness retreats, and meditation. While there is nothing inherently wrong with any of those practices, it is absurd to believe that yoga will solve the problems of treating a cancer patient with a declined preauthorization for chemotherapy, having no time to discuss a complex diagnosis, or relying on a computer system that places metrics ahead of communication. These problems are not the result of some failing on the part of the individual clinician.”

Texas physicians agree that “burnout” isn’t an appropriate word.

“Burnout is a hard term. A lot of people think that makes the [situation] look like it’s the physician’s fault, and not the fact that really, all the circumstances have happened to them, [and] it’s almost a natural response,” Dr. Fite said. “Moral injury makes better sense.”

Dr. Greenberg adds that for what he’s witnessed during the pandemic, “beat down” is a more appropriate term than burnout.

“People, they’re just really tired,” he said. “They’re not ready to turn in their careers for it, but man, they’re just tired. It’s like everything is 10 times harder than it has ever been.”

Prescriptions for a turnaround

Whatever the term used, moral injury in medicine was already a problem before the pandemic began. Even after COVID-19 is minimized or eradicated, its effects on the physician psyche won’t go away overnight.

In Dr. Swegler’s view, medicine will need execution of four high-level action items to work its way out of the long-term burnout/moral injury malaise: Payment reform; doing more to reduce administrative burden such as prior authorizations; improving interoperability of technology systems such as electronic health records; and reforming how disciplinary processes handle certain byproducts of burnout, such as substance use disorder.

“It’s not the physician that needs to be healed. It’s a system that needs to be healed, and I want to make that abundantly clear,” she said. “It’s not that I need to do more yoga, or spend time meditating. Fix the system. There’s nothing inherently broken about myself.”

System repair is a long-term project, but TMA offers a host of courses that can help physicians practice needed self-care and also earn CME credit. (See “TMA’s Wellness CME,” below.)

Dr. Bailey said in December that AMA was in the process of conducting a new survey following a pre-pandemic poll, published in 2019, that showed 44% of physicians had exhibited at least one symptom of burnout in 2017.

AMA released mental health coping tips last year for navigating the pandemic (tma.tips/amamentalhealth).

Along with the new survey, Dr. Bailey said, AMA is engaging in ongoing physician education about the efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines – which she says is key to gaining patient buy-in as well. She said AMA is also focused on making sure physicians have access to adequate PPE, and complimented TMA on its PPE distribution efforts. (See “COVID-19 Resource Guide,” page 27.)

Tex Med. 2020;117(2):16-21

February 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page