For many patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), there’s a lot to dislike about a trip to the doctor.

Some don’t like new or unusual experiences; others don’t like to be around people in a waiting room; still others don’t like to be touched – all potential pitfalls for a physician greeting a patient with ASD in the exam room, says Flower Mound pediatrician Michelle Forbes, MD.

“Children with autism see the world differently,” said Dr. Forbes, a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Medical Home and Primary Care who frequently treats patients with ASD. “What I find important is to understand from the family how does the child like to be examined. That really is the biggest barrier – learning what the child needs.”

Meeting those needs is important because ASD is a fast-growing, serious developmental disability in the U.S., affecting an estimated one out of 59 children nationally, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is about four times more common in boys than girls.

In recognition of its growing importance, TMA’s House of Delegates in 2019 approved a resolution encouraging physicians to expand and promote resources for families of people with autism. (See “Improving Autism Services,” below.)

The resolution is designed to lower some of the communication barriers between physicians and families of people with ASD, says Pruthali Kulkarni, a co-author of the resolution and a fourth-year medical student at the University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine.

An acquaintance of hers in the medical field has a young son with autism, and the child’s mother has been frustrated that some physicians have not thought to refer her to resources that could help her son.

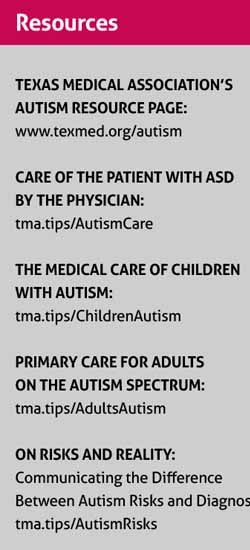

“A lot of health care providers from her standpoint weren’t willing to go the extra mile in reaching out to [connect families with] resources that are available in the state of Texas to help these patients with autism,” said Ms. Kulkarni, who co-chairs the TMA Medical Student Section. (See “Resources,” page 44.)

Dr. Forbes agrees that many families are in the dark in that regard.

“A lot of [my] time is spent educating the family about resources,” she said.

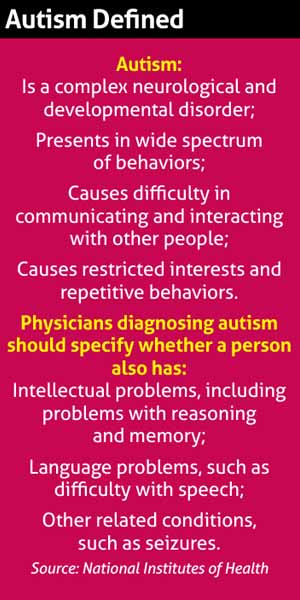

ASD can be difficult for families to handle alone. Autism has no known cause, though genetics plays a role, and it is a complex neurological and developmental disorder that presents a wide spectrum of behaviors, according to the National Institutes of Health. (See “Autism Defined,” right.)

Physicians also can look for better ways to accommodate patients with ASD, says Joyce Mauk, MD, a Fort Worth pediatric specialist in neurodevelopmental disabilities and developmental behavior. It’s tempting to look for a formula, but that formula just doesn’t exist because the spectrum of behaviors is so wide.

“They’re individuals like everyone else,” she said. “To have an autism-friendly practice to me is a misnomer. You should have a practice that’s people friendly. People [with disabilities are not] strangely different from everybody else, and they’re very different from each other.”

Special needs

A large percentage of Dr. Forbes’ practice consists of patients with special needs, including those with ASD, she says. Once she started working with those patients, she found she liked it.

“It’s so multi-faceted,” Dr. Forbes said. “There’s the health component and there’s the mental health component and there’s the success – academic and social success [of the patients]. There are so many components that make it enjoyable for me.”

Disruptive behavior at the doctor’s office can be a big problem among young patients, but it becomes a larger problem in treating young children with developmental disabilities, Dr. Mauk says.

“There’s a higher percentage of children who are nonverbal, and who are not able to communicate well,” she said. “But typically, their parents are able to understand what’s bothering the patient.”

Parents usually can guide a child and the physician through an exam in a way that minimizes disruption, Dr. Mauk says. In the most challenging cases, the patient may scream or hit whomever is working with him or her. At that point, the physician needs to be clear that the exam will take place no matter how the patient behaves, she says.

“For me, the most important thing to recommend is you still have to examine them and check them,” she said. “You can’t allow behavior to let them get out of medical care. The main thing is to not show too much attention to the bad behavior, but then to reinforce when they are being cooperative.”

Equally important is for physicians to not let bad behavior get them rattled.

“It can be very difficult,” Dr. Mauk said. “And I think it is important to have a soothing demeanor and not be difficult yourself.”

Staff should be equally calm and professional, she says. Staff members also should get trained in techniques for guiding patients with ASD in a constructive direction for both medical and non-medical needs. For instance, some patients are bothered by getting their hair cut because it requires physical contact. The best way to help patients prepare is to rehearse cutting the hair with an electric shaver or scissors – perhaps many times – before actually doing it, Dr. Mauk says.

Parents may request that physicians modify the environment to keep a child from behaving badly, Dr. Mauk says. For instance, they might ask that a physician have no one in the waiting room or to dim the lights or mute the television volume to avoid triggering bad behavior. But that kind of request is not realistic for the medical practice, she says. And it makes assumptions about what is causing the child’s behavior

“Sometimes what you have to do is help get them over that hump and get them into the room,” Dr. Mauk said. “And then they see that it’s OK.”

Going that extra mile

Unfortunately, physicians often have to deal with several layers of bureaucracy in going the extra mile to help their patients get coverage for additional therapy. But a physician’s diagnosis is integral to helping patients receive such benefits, which the Texas Legislature recently expanded. (See “New Autism Benefit in Texas Medicaid,” above.)

From birth to age 3, patients with ASD receive therapy and other benefits through Early Childhood Intervention, a program of the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. At 36 months of age, their services switch over to the local school district.

That can present problems for physicians because the level of benefits varies greatly, depending upon the school district, which in turn can affect the patient’s health or the family’s stress level, Dr. Forbes says.

“Interfacing with the school, interfacing with the case manager, having to interface with the medical director – that’s an extra step [for physicians treating patients with ASD], and it’s tough to find time to schedule a phone conference to advocate for patients in multiple levels of an organization. And it’s unreimbursed. It’s worth it to get the services, but that is an additional challenge [for the physician].”

Adult patients with ASD typically lose those benefits after high school, Dr. Mauk says.

“It becomes a problem [for the patient’s health],” she said. “Most schools, depending upon the level of severity of the autism, do what they can to prepare the child for as independent a life as possible [as an adult]. But for most of my patients, the parents anticipate providing a higher level of care into adulthood.”

One of the best ways to compensate for this lack of state benefits is to make sure that patients are plugged into as many community resources as possible, says Ms. Kulkarni, the medical student.

“A lot of these individuals fall through the cracks in getting preventive care,” she said.

Tex Med.

2019;115(12):42-44

December 2019 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main

Page